This is part four in an occasional series that asks people who work in and around heritage to tell us their favourite buildings and the one that we should never have destroyed.

Anne Banner is the proprietress of Salmagundi, an antiques, oddities and novelties shop located in the J.W.Horne Block.

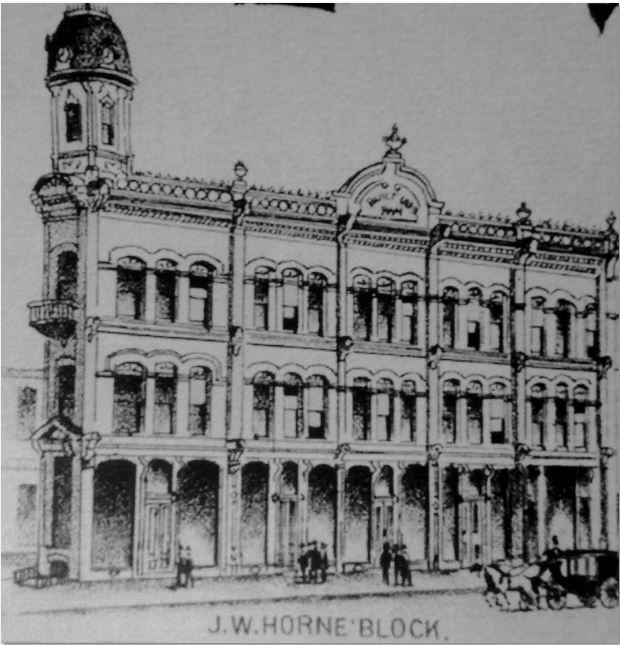

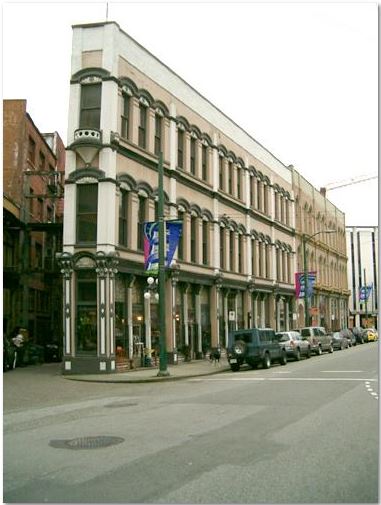

My favourite existing building in Vancouver is the J.W.Horne Block. The building runs from 311-321 West Cordova Street in Gastown. Construction started shortly after the Great Fire of 1886 and it was completed in 1889.

This brick, flat iron building is still standing, but last century it was much more exquisite and has lost much of its former beauty. Gone are the Victorian Italianate architectural details. In the early days the building had a magnificent turret and cornices decorated with a Freemason motif. Although these design elements have been erased it’s still my favourite building because it’s old and has a ton of character both inside and out.

Tom Carter has been painting historical views of Vancouver for many years, and has artwork in prominent private and corporate collections. Tom is on the board of the BC Entertainment Hall of Fame. You can read more about his work in Vancouver Confidential “Nightclub Czars of Vancouver and the Death of Vaudeville.”

Favourite existing building:

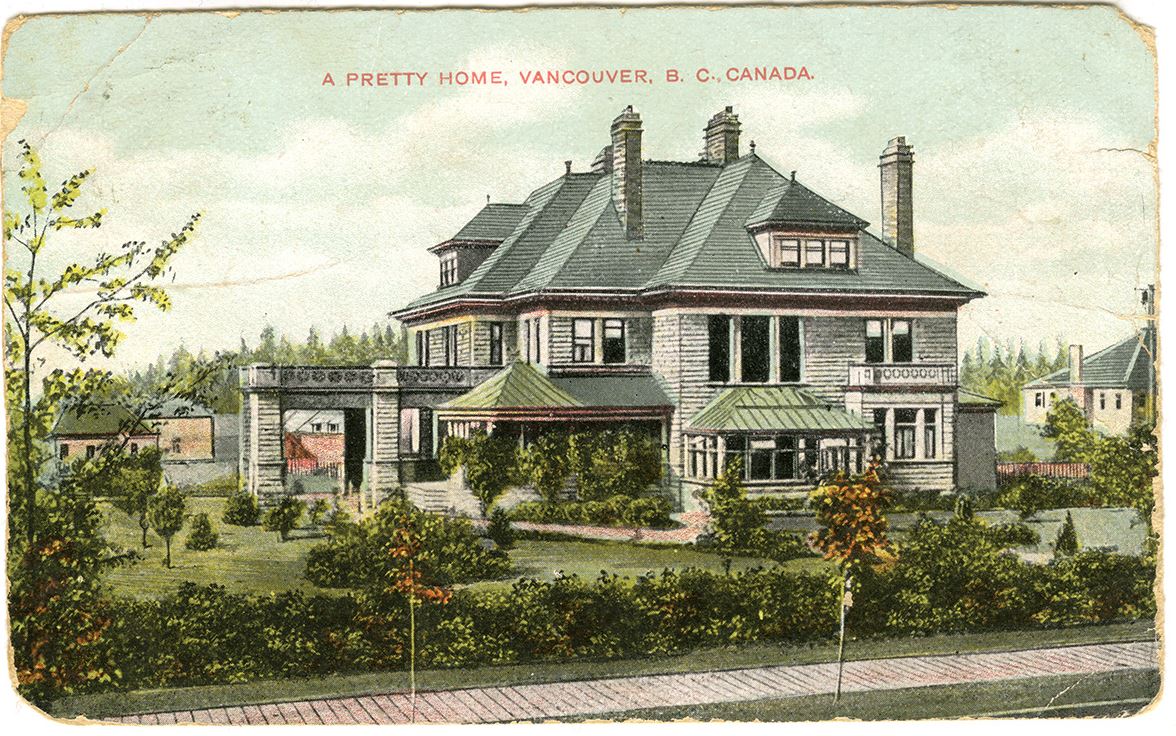

It’s a miracle that Gabriola has survived. The old Rogers mansion is the last of the West End mansions, since the Legg house was demolished last year. It’s also probably the best of the bunch, as it was used in all sorts of early Vancouver promotional materials as an example of a typical “pretty home”. Clearly not typical then or now! The design is spectacular, as is the workmanship and the incredible piece of stained glass over the stairway.

The building that we never should have torn down:

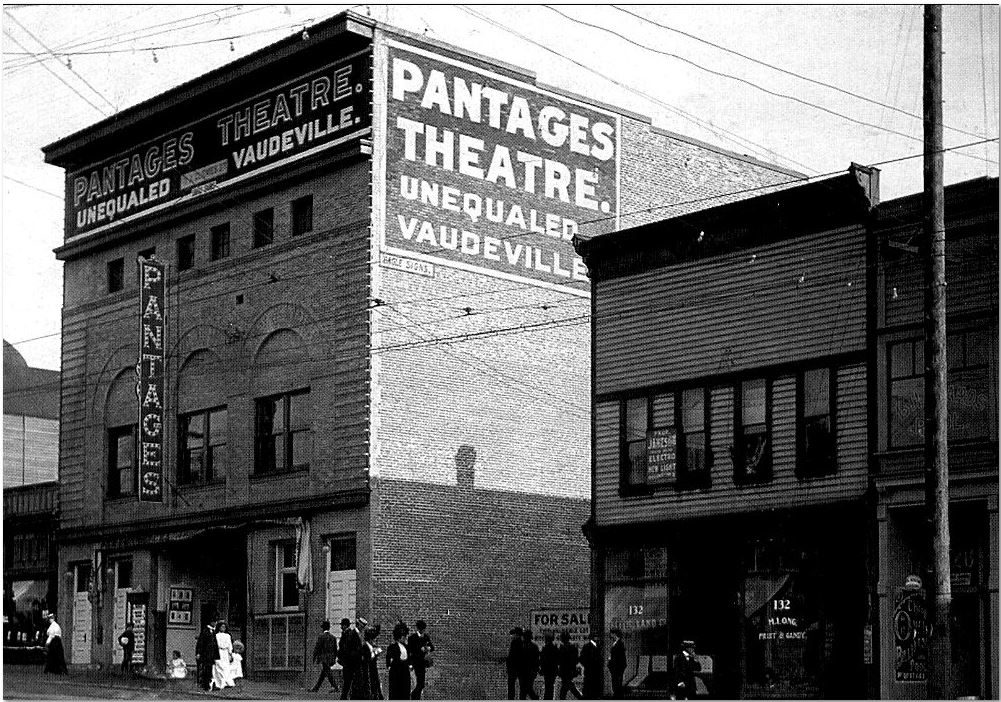

The first Pantages at Hastings near Main was torn down just a few years ago. As the oldest surviving Pantages, the oldest surviving vaudeville theatre in Canada and a building where a lot of Vancouver history played out, the theatre was clearly important historically. It had an incredible restoration plan, a lot of public support, and would have provided a theatre/meeting space that will actually be needed in this neighbourhood. Its loss was preventable, a tragedy for theatre history nationally, and a loss to the DTES community. Our city council really bungled this one up!

Kerry Gold is a born and raised Vancouver journalist who is a contributor to Vancouver Vanishes: Narratives of Demolition and Revival. Kerry also writes a real estate column about heritage preservation, housing affordability and Vancouver’s growth and transformation for the Globe and Mail.

Favourite building:

I love this little house, which is in my neighbourhood, because it is small, and in perfect proportion to the corner lot it sits on. It still has the mullioned windows on both the front porch and back sunroom. It’s basically a cottage within the city, and I suspect the owners love it too, because of the maintenance of its original details, including an era-appropriate font used for the address numbers. The house must be circa 1910, an ode to the days when it was all about the details, not the square footage.

The building that we should not be tearing down:

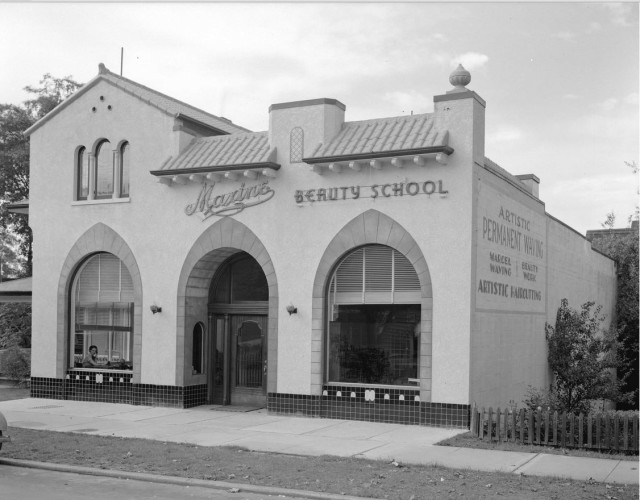

The Mercer and Mercer art deco inspired building at the corner of East Hastings and Gore was built in the late 1940s for the Salvation Army and spent time as a Buddhist temple before BC Housing purchased it and used it for storage. Now, it’s up for redevelopment, which is tragic because we don’t have many deco designs left from that era. Enough with the endless rows of green glass and concrete towers. Our architecture is mind-numbingly boring. Let’s preserve this beautiful old building and bring history and colour to the downtown eastside.

Anthony Norfolk is a retired lawyer and past President of the Community Arts Council of Vancouver and of Roedde House Preservation Society. His longstanding record of Heritage Advocacy was recognised by a City of Vancouver award in 2011. He currently sits on the City’s Heritage Commission.

Favourite building:

Is, not surprisingly, Roedde House. Now a museum, and part of Barclay Heritage Square, Roedde House is a survivor from the early development of the West End. It was built in the Queen Anne style for the Roeddes in 1893 and designed by Francis Rattenbury with one of the architect’s characteristic turrets on one side. The museum celebrated its 25th anniversary in 2015.

The building that we never should have torn down:

The first Pantages Theatre (1907) on Hastings Street just west of the Carnegie Centre at Main Street. When City Opera Vancouver was looking for a home I steered them to the vacant and deteriorating Pantages, and to the late Jim Green. With the support of the owner, a plan was developed for City Council to purchase the theatre and adjoining properties. The theatre would be restored, and a social housing development constructed. Unfortunately, when the theatre was demolished due to neglect in 2011, Council was still studying the proposal.

See previous Heritage Streeters:

- With John Atkin, Aaron Chapman, Jeremy Hood and Will Woods

- With Caroline Adderson, Heather Gordon, Eve Lazarus and Stevie Wilson

- With Michael Kluckner, Jess Quan, Lani Russwurm and Lisa Anne Smith