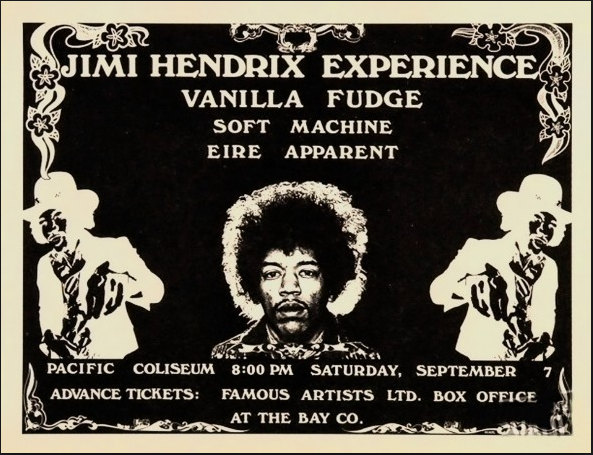

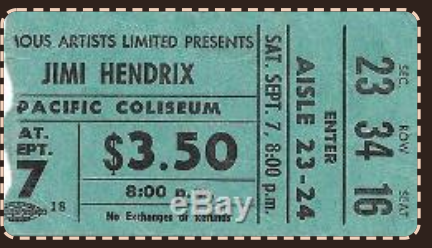

Long before Jimi Hendrix played the Pacific Coliseum on September 7, 1968, he had a Vancouver connection.

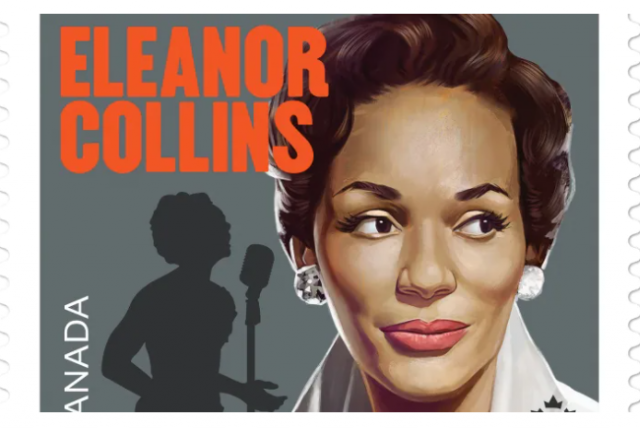

Jimi Hendrix played the Pacific Coliseum on September 7, 1968. Four years after the Beatles and 11 years after Elvis Presley played Empire Stadium and changed music forever. The difference was that Jimi had a Vancouver connection—his grandmother Nora Hendrix, a one-time vaudeville dancer who moved to Vancouver in 1911 with her husband Ross Hendrix, a former Chicago cop and raised three children. Al, the youngest moved to Seattle at 22, met 16-year-old Lucille, and Jimi was born in 1942.

Jimi Hendrix played the Pacific Coliseum on September 7, 1968. Four years after the Beatles and 11 years after Elvis Presley played Empire Stadium and changed music forever. The difference was that Jimi had a Vancouver connection—his grandmother Nora Hendrix, a one-time vaudeville dancer who moved to Vancouver in 1911 with her husband Ross Hendrix, a former Chicago cop and raised three children. Al, the youngest moved to Seattle at 22, met 16-year-old Lucille, and Jimi was born in 1942.

Story from At Home with History: the secrets of Greater Vancouver’s Heritage Homes

According to Jimi Hendrix, the Man, the Magic, the Truth, a biography published in 2004, Jimi lived in 14 different places, including short stints in Vancouver. “I’d always look forward to seeing Gramma Nora, my dad’s mother in Vancouver, usually in the summer. I’d pack some stuff in a brown sack, and then she’d buy me new pants and shirts and underwear. I kept getting taller and growing out of all my clothes, and my shoes were always a falling-apart disgrace. Gramma would tell me little Indian stories that had been told to her when she was my age. I couldn’t wait to hear a new story. She had Cherokee blood. So did Gramma Jeter. I was proud of that, it was in me too.”

According to the Vancouver School Board Archives and Heritage, in 1949, Jimi attended grade 1 at the West End’s Dawson Annex while living at Nora’s house on East Georgia. “It was a long distance to the school so he probably took the bus or streetcar since the fare was only five cents,” notes the VSB.

Shortly after Hendrix left the army in 1962, he hitchhiked 2,000 miles to Vancouver and stayed several weeks with Nora. He picked up some cash sitting in with a group at a local club on Davie Street, now a gay nightclub called Celebrities.*

Six years later, when Jimi Hendrix Experience played the Pacific Coliseum, one reviewer described the band as “bigger than Elvis.” Hendrix, dressed all in white, played hits such as “Fire,” “Hey Joe,” and “Voodoo Child.” At one point he acknowledged his grandmother, who sat in the audience, and launched into “Foxy Lady.”

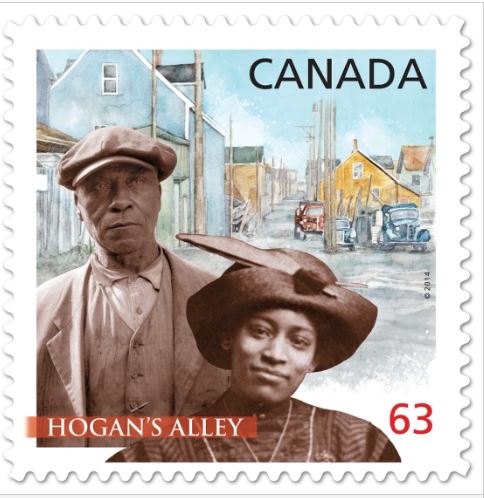

In 2002, Vincent Fodera renovated the building at Union and Main Street and found dishes and a stove that he believes came from Vie’s Chicken and Steak House, part of Hogan’s Alley where Nora once worked as a cook. Seven years later Fodera opened a shrine for the dead rock star. Locals told him that Jimi used the space for rehearsals and sex.

When Jimi played the Pacific Coliseum in 1968 he was 25. Just over two years later, the man widely recognized as one of the most creative and influential musicians of the 20th century was dead.

- 1022 Davie Street was designed by architect Thomas Hooper for the Lester Dancing Academy in 1911. Hooper also designed the Victoria Public Library, and Munro’s Books Building in Victoria. And in 1912, the same year he designed Hycroft in Shaughnessy, Vancouver’s Winch Building and submitted plans for UBC, he designed Christina Haas’s, Cook Street brothel

Related:

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.