Edgemont Village, North Vancouver. Then and Now: 1949-2023

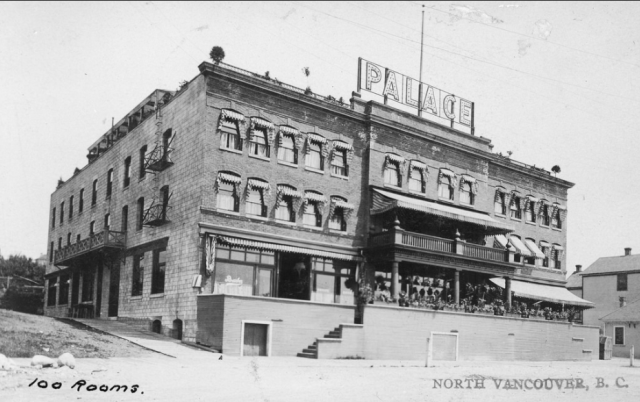

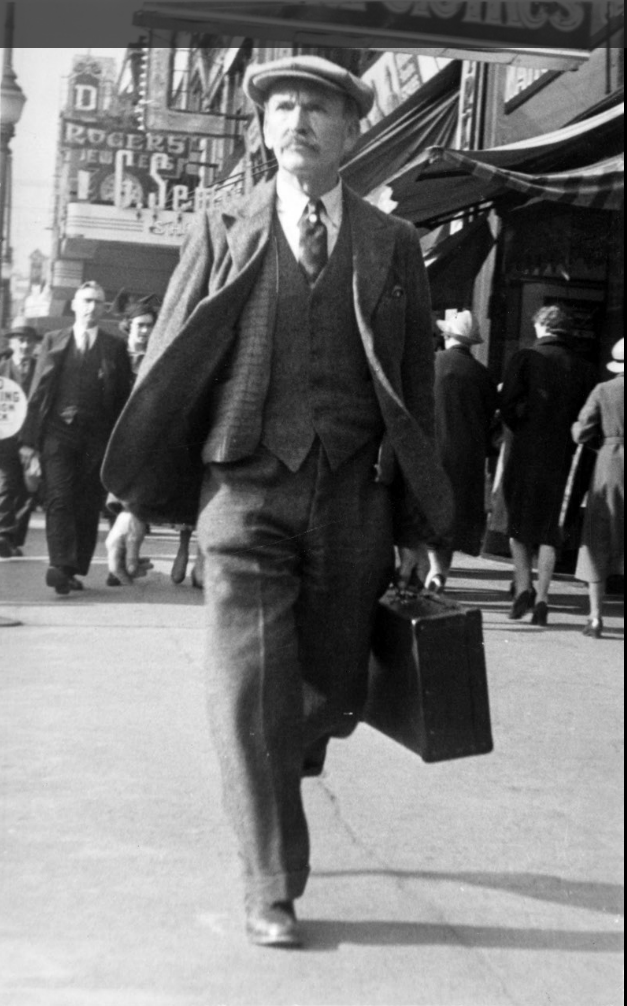

I came across this photo from the North Vancouver Museum and Archives a while back. It shows a fairly ordinary looking building on Edgemont Boulevard taken in 1949. I headed off to Edgemont Village last week to see what we’d replaced it. Instead, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the building is still there, surrounded by other buildings.

Then I poured a glass of wine and opened up city directories.

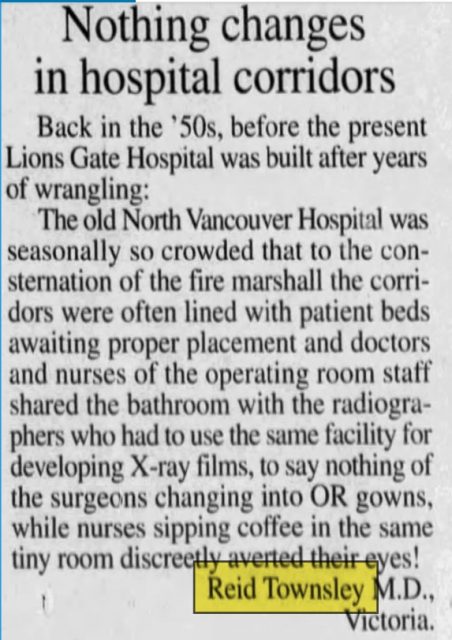

In January 1949, Dr. Reid Townley occupied 3028 (left), next door to the Edgemont Beauty Salon. That year, the only other building between West Queens and Highland was the Queen’s Market grocery on the corner (which 74 years later is still a grocery) and Bob’s meats next door.

According to BC Assessment, it was built in 1949 the same year the photo was taken.

Today, Dr. Townley’s office is occupied by Kim’s Hair Studio and the former beauty salon is now a Subway.

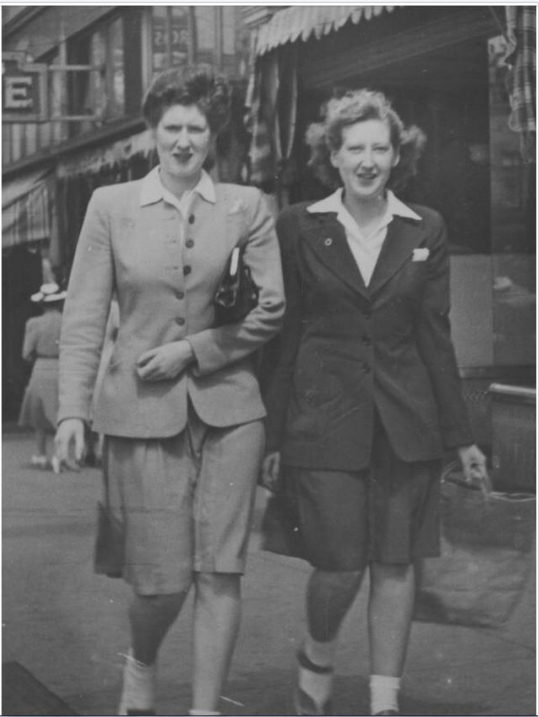

I was curious about Dr. Townley, the first occupant of the building. According to a 2007 obituary in the BC Medical Journal, he was an interesting guy. He was born in Ontario, went to Queen’s University in 1938, survived the war, and interned at St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver. He met Esther on a ferry from Victoria, married in 1945 and they stayed married until his death 62 years later.

The couple lived on the North Shore, and when he wasn’t doctoring, Townley fell in love with sailing.

By 1953, city directories show Townsley had closed his Edgemont Boulevard practice, most likely because he was studying anesthesiology. In 1958, Townsley worked at Lions Gate Hospital. He and Esther had three kids, and retired to Salt Spring Island in 1980.

Dr. Guy Winch, his friend and colleague wrote in his obituary: “He was a quiet-spoken man, always thoughtful, with a delightfully subtle sense of humor. In addition to medicine, he had a great love of good literature, music, and art. He was an excellent sailor and skipper and taught me most of what I know about sailing, for which I shall always be indebted. He was a charming companion, an excellent doctor, and altogether a lovely man.”

I can’t think of a better way to end a story or a man’s life.