This is an excerpt from Sensational Vancouver.

Eleanor Lum

Wayne Avery knew nothing about the history of his house until one day he saw an elderly Chinese woman peering through his front room window.

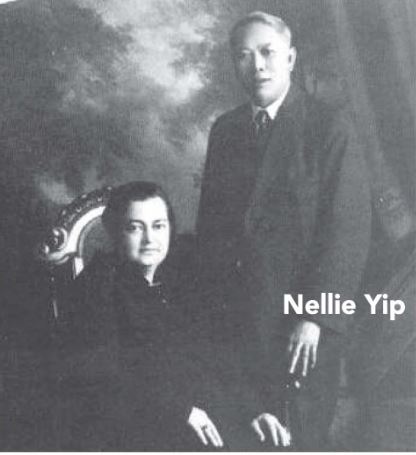

He invited her inside and discovered that she was Eleanor (Yip) Lum, and that she had been born in one of the bedrooms of his Strathcona house in 1928 by Nellie Yip Quong who later adopted her.

Nellie was not Chinese as her name suggests, but a white Roman Catholic, born Nellie Towers in Saint John, New Brunswick and educated in the United States. It was while she was teaching English in New York City that she met and fell in love with Charles Yip, a jeweler from Vancouver.

Yip Sang

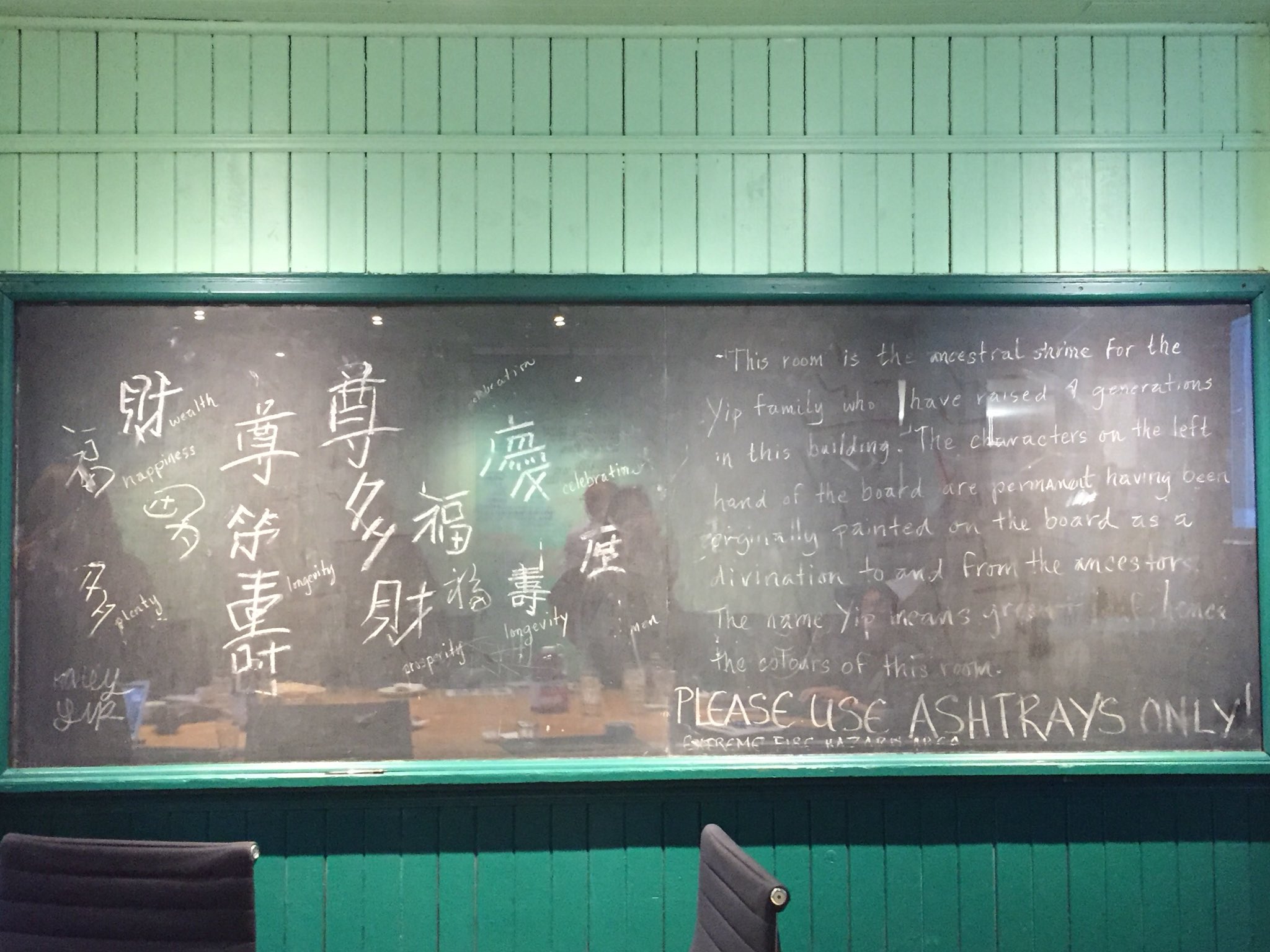

Charles was the nephew of Yip Sang, a wealthy merchant who built the Wing Sang Building on East Pender Street in 1889. The building was erected to house Yip Sang’s growing import/export operation, an opium production plant, and his family–three wives and 23 children–one wife per floor.

When they married in 1900, Nellie was disowned by her family and spurned by the church. The couple lived in China for a few years, then moved to Vancouver in 1904 to live with Charles’s uncle Yip Sang at the Wing Sang building.

Advocate

Nellie learned how to communicate with the Chinese and with the authorities who ignored them. She fought on the behalf of the Chinese. She challenged the justice system and shamed the Vancouver General Hospital into moving non-white patients out of the basement. When the White Lunch restaurant put up a sign saying “No Indians, Chinese or dogs allowed,” Nellie made them take it down. She arranged care for the elderly, brokered adoptions, acted as an interpreter, and became the first public health nurse hired by the Chinese Benevolent Association.

Nellie and Charles moved into their East Pender Street house in 1917.

Nine decades later, Wayne took Eleanor through the house where she had grown up. She’d stop here and there and point out something from her past. She told Wayne that Charles did the cooking and the gardening, and one of her favourite memories of Nellie—a large imposing woman—was her wearing a wide hat with a feather in the side and reading a Chinese newspaper on the bus.

During the renovation, Wayne had discovered that at different times his house was once a bootlegging joint and a brothel. He found old Finnish newspapers beneath the floor, cartons of cigarettes stashed in the ceiling, booze in a secret hideout in the garden, and locks on the inside of the bedroom doors. He found that in 1911 Nora and Ross Hendrix, grandparents of rock star Jimi Hendrix, lived in his home.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.