Before the Vancouver Art Gallery moved into the old courthouse on West Georgia, its home was a gorgeous art deco building a few blocks away.

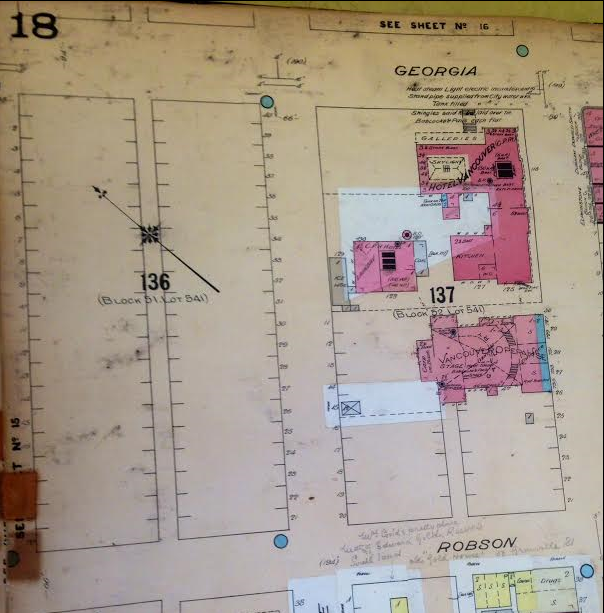

If you live in Vancouver, you know that the Vancouver Art Gallery is housed in the old law courts, an imposing neo-classical building designed by celebrity architect Francis Rattenbury in 1906. What you may not know, was that the VAG started out in a gorgeous art deco building at 1145 West Georgia, a few blocks west from its current location.

Story from Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

The original 1931 building—the same year the VAG was founded—was designed by local architects Sharp and Thompson. George Sharp, a respected artist and founding faculty member of the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts designed the building to fit perfectly into the largely residential West End neighborhood. It had a main hall, two large galleries and two smaller ones with a sculpture hall, library and lecture hall.

Charles Marega won the commission to sculpt the heads of Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci that flanked the front door. Marega carved the names of those who were considered great painters of the times (none were Canadian and all were men).

After the war, Group of Seven artist Lawren Harris, who lived on ritzy Belmont Avenue, raised $300,000, and the building was expanded to three times its original size to accommodate the works of Emily Carr and some of Harris’s own paintings. The Art Deco façade disappeared and Marega’s sculptures were no longer considered appropriate for the new sleeker modern building.

The VAG ran a classified ad in the Province in July 1951 offering the sculptures for sale. If they didn’t sell, the plan was to throw them out. Rumour has it that they found a home somewhere in the Lower Mainland – and if you happen to have them in your backyard, please let me know!

In 1983, the VAG moved into its current digs at the old courthouse taking with it $15 million in art. Two years later the original building was demolished. Now the Paradox Hotel (former Trump tower) and the FortisBC Centre straddle its old space.

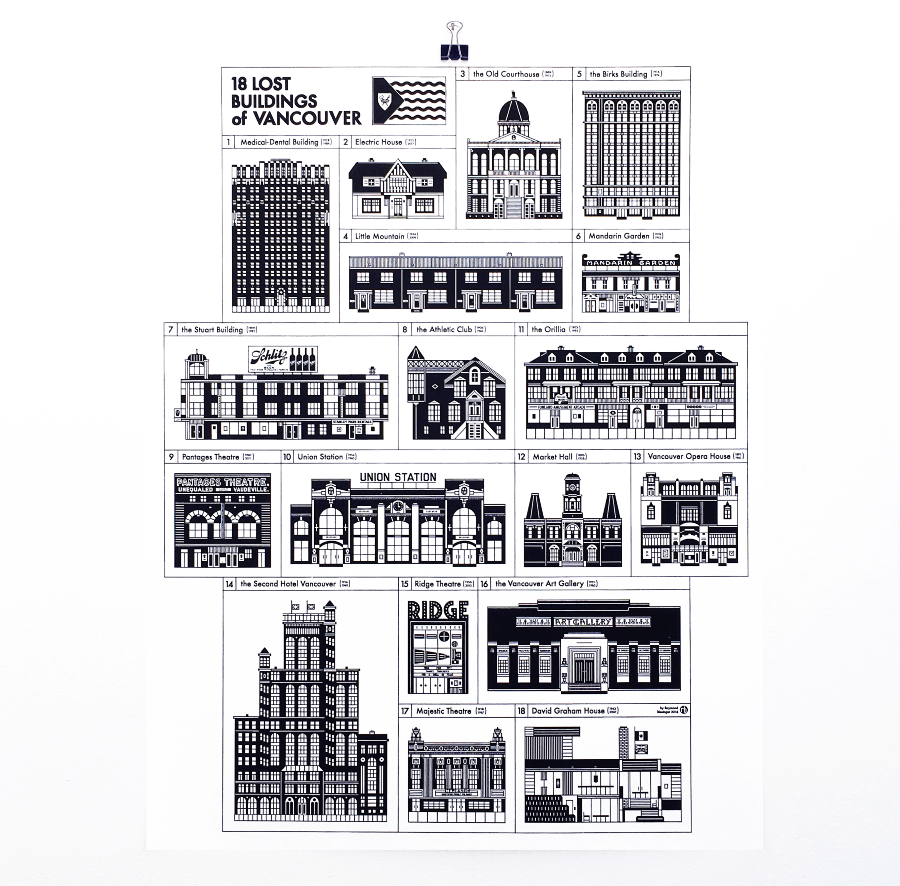

For more in Our Missing Heritage Series see:

Our Missing Heritage (part one) The Georgia Medical & Dental Building and the Devonshire Hotel

Our Missing West Coast Modern Heritage (Part two)

Our Missing Heritage (part three) The Empress Theatre

Our Missing Heritage (part four) The Strand Theatre, Birks Building and the second Hotel Vancouver

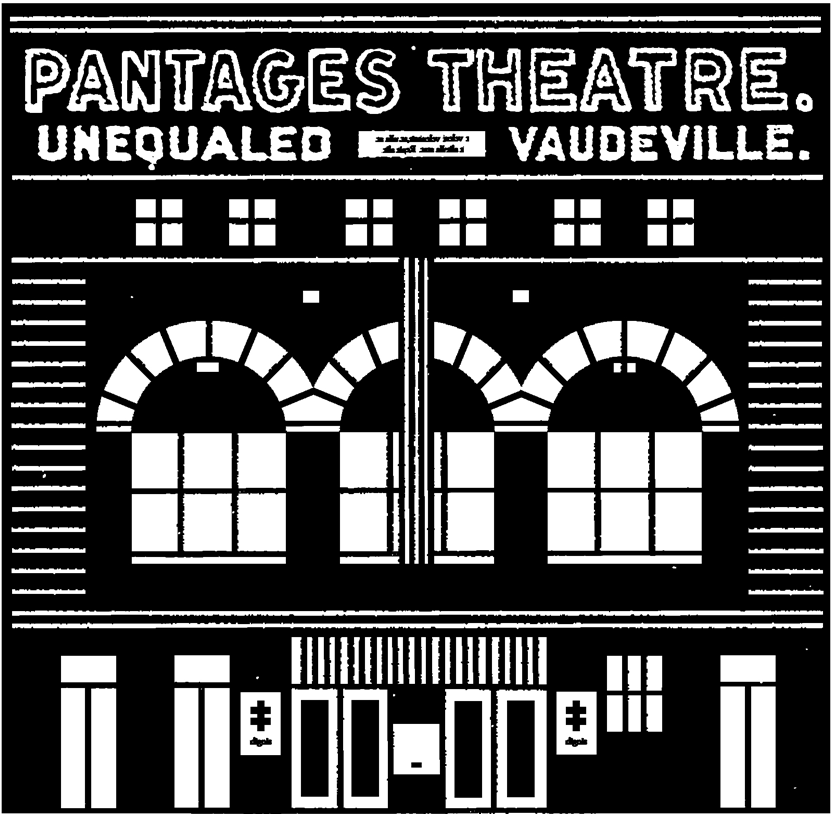

Our Missing Heritage (part five) The Hastings Street Theatre District

Currently, the new $9.6 million dollar plaza at the VAG showcases a very European Monet poster. I would have preferred to see the invocation Jensen wrote about that site:

Currently, the new $9.6 million dollar plaza at the VAG showcases a very European Monet poster. I would have preferred to see the invocation Jensen wrote about that site: