Thursday November 25 is International Day. Remembering Olga Hawryluk, 23, murdered May 3, 1945.

From Blood, Sweat, and Fear: The Story of Inspector Vance and the Blood, Sweat and Fear podcast.

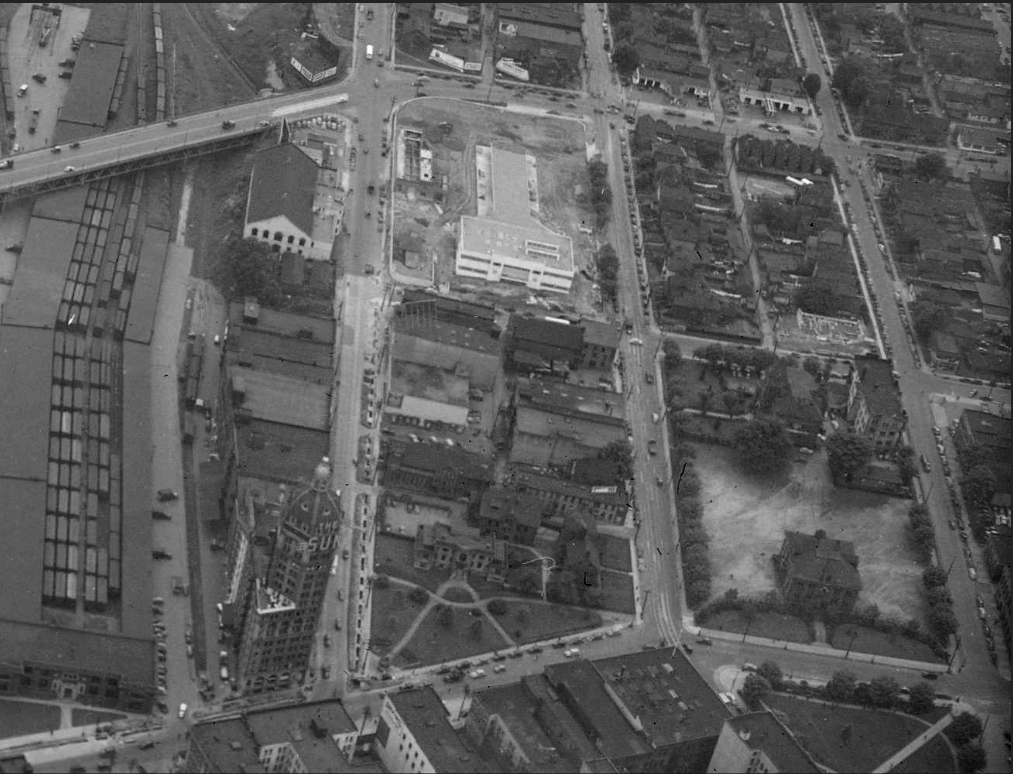

Granville Street:

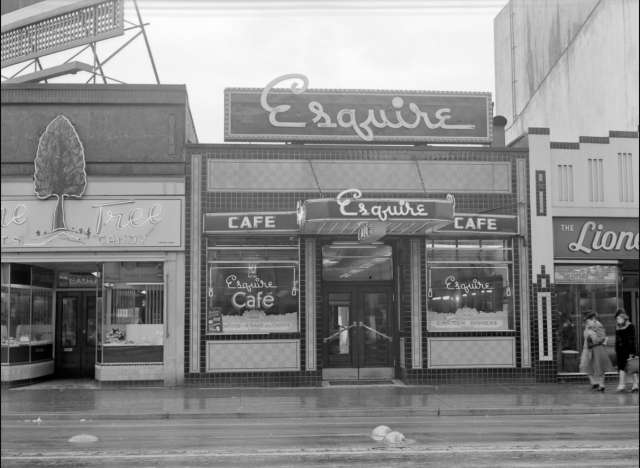

On May 2, 1945, Olga finished her shift at the Empire Café on West Hastings at 2:30 am and was walking to her home in the West End. She noticed a man following her and stopped in at the Good Eats Cafe on Granville Street to try and get rid of him.

Olga sat on a stool at the counter near the front door. May Chalmers, who was working that night, saw a tall civilian dressed in a grey coat and hat follow her inside. Olga clearly didn’t know him and told him to go away. May told him to get out of the café.

Olga ordered a coffee and chatted to a soldier sitting on the stool next to her. Rose Uron, the cashier, heard the soldier ask Olga out and Olga refuse. When he tried to pay for Olga’s coffee, Rose told him that Olga would take care of her own bill. Rose asked Olga to wait in the café for a little while before heading home, but Olga told her she would be fine and left.

English Bay:

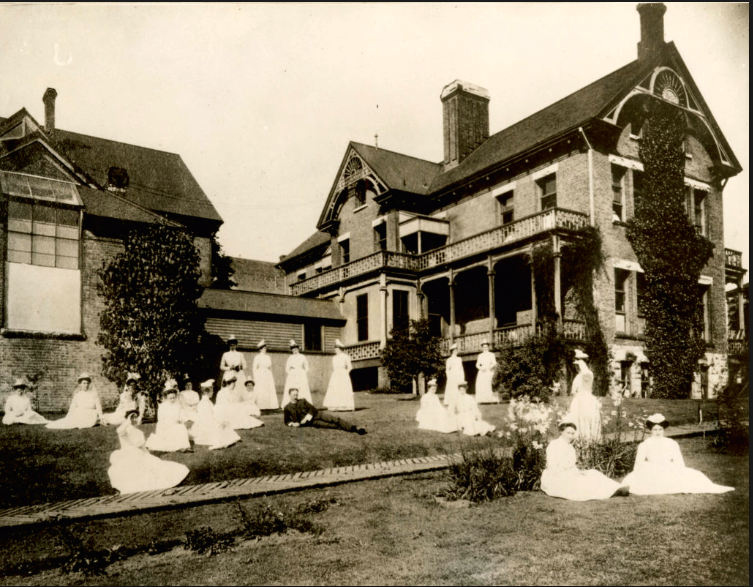

Georgina Robinson and her daughter Hazel were on holidays from Calgary, where Hazel was a writer. They were staying at the English Bay Mansions when they were woken by a woman screaming “Help me! Help me! God help me!”

Hazel went into the kitchen and phoned police. She threw on some clothes, grabbed a flashlight and ran through Alexandra Park, passed the monument to Joe Fortes, and down to the beach. She saw a soldier near the water. The fearless Hazel ran after the soldier and shone her flashlight in his face. He turned away from her and walked quickly down Beach Avenue.

When Hazel returned to the beach, she followed a trail of blood on the sand where a body had been dragged down to the water. Others had gathered and could see a woman lying face down in the water. When they turned her over it was obvious that she was dead.

Police arrested William Hainen on Drake Street on the way to his room in the Astoria Hotel on West Hastings. He had cut his hand and broken a finger. There was blood on his uniform and sand in his hair.

The Trial:

Angelo Branca represented Hainen. Over his career he had defended 63 people on murder charges, and only one—Domenico Nasso received the death penalty in 1928. Branca established that Hainen drank a 13-ounce bottle of rye at noon the day before the murder, up to 30 beers between 2:00 and 8:00 pm, another 15 beers between 9:30 and 11:00 pm and more than half a bottle of rye after that. Branca argued that Hainen was too drunk to know what he was doing. It didn’t work, Hainen was executed at Oakalla Prison Farm on October 20, 1945.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.