On June 4, 1965, CKNW personality Rene Castellani climbed to the top of the scaffolding next to the BowMac Sign and promised not to come down until every last car on the lot was sold.

It took nine days.

The following story is an excerpt from Murder by Milkshake: An Astonishing Story of Adultery, Arsenic, and a Charismatic Killer.

Bowell McLean Motor Company

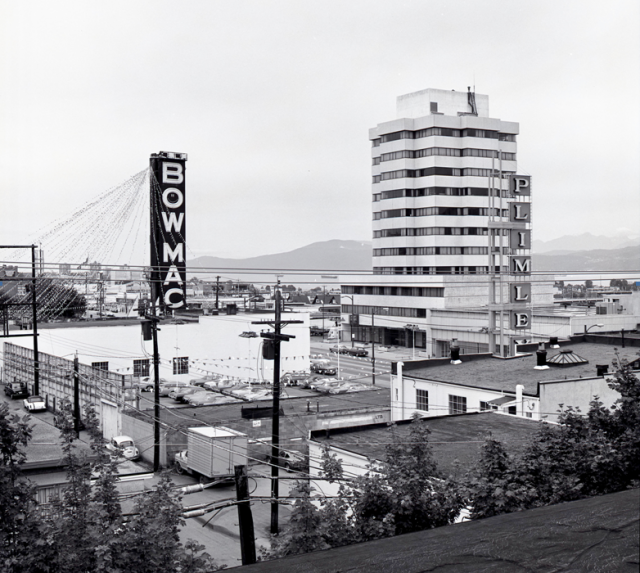

These days, the scene takes a bit of imagination. Auto row and the Bowell McLean Motor Company on West Broadway are long gone. The giant neon sign has been neglected and was partially covered over by the current tenant—Toys-R-Us—more than 20 years ago.

But back to 1965.

Jimmy Pattison:

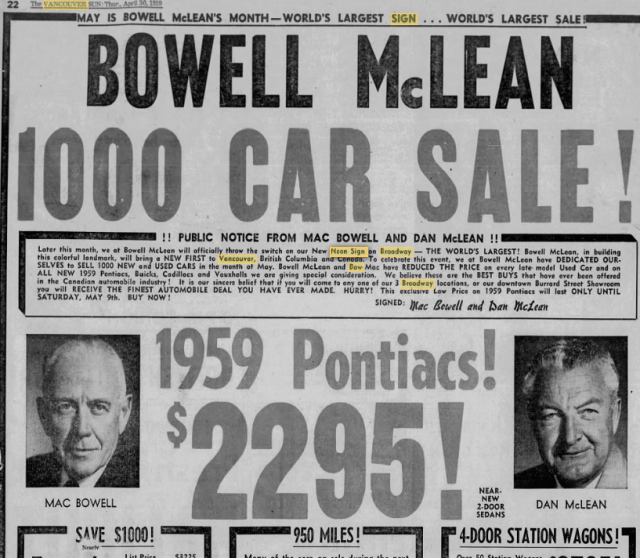

The BowMac car dealership had a history of staging stunts to lure customers away from the Dueck Chevrolet Oldsmobile dealership down the road. Under Jimmy Pattison’s management, promotions included dressing up a performing monkey in overalls and hiring the Leavy brothers—seven-foot-tall twins—to hang out in the used car lot. In 1958, Pattison staged what was billed as the “world’s largest checker game” where models in red or black bathing suits became the checkers moving across a board of two-foot squares.

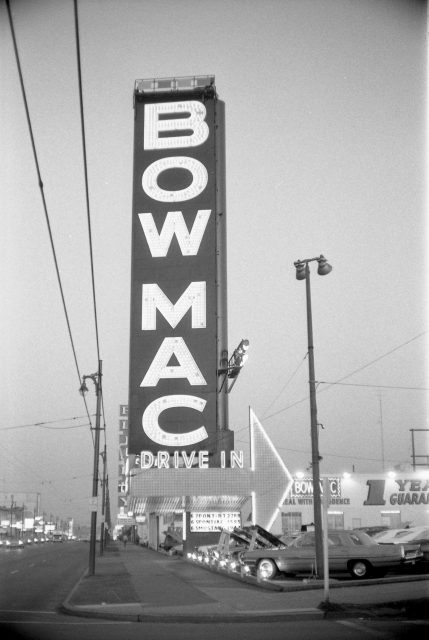

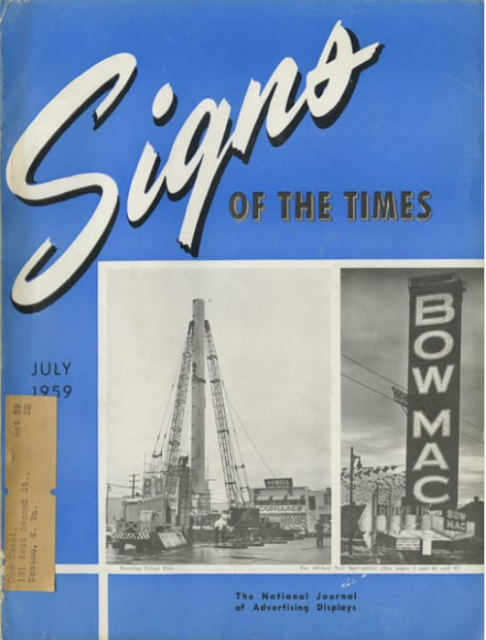

Pattison topped that the following year when he commissioned Neon Products (a company he later brought) to build a sign the height of a seven-storey building. It had orange and red letters that spelled BOWMAC, powered by a transformer that could light up 30 houses.

The sign cost $100,000, weighed 12 tons, and was briefly North America’s largest free-standing sign.

Guy in the Sky:

Castellani’s assignment was called “the Guy in the Sky” and the stunt called for him to live in a station wagon next to the neon sign. The station wagon was equipped with a telephone and a direct line to CKNW, bedding, and a chemical toilet. Food was sent up to him in a bucket. The car was brightly lit, and he was quite visible from the ground most of the time. He would give regular broadcasts from the tower. Passerbys were encouraged to drive by and honk their horns, and they could see a clothesline strung from the station wagon to the sign with a pair of Castellani’s shorts swaying in the wind.

Capital Murder:

The BowMac Sign promotion became a central part in Castellani’s capital murder trial for the arsenic poisoning of his wife Esther. A Toronto lab was able to use a nuclear reactor to chart the progress of arsenic in Esther’s hair and fingernail growth and provide a rough timeline of when she received the poison and in what quantities. Esther, who had been in Vancouver General Hospital for the nine-day duration of the promotion, had greatly improved while Castellani was away. On the day after he came back down from the sign, she got really ill and never recovered. It coincided with the charts that showed she had received a massive dose of arsenic while she was in hospital and sometime within 35 days of her death on July 11, 1965.

Update:

As for the sign, it was the subject of a Heritage Revitalization Agreement in 1997 where Toys-R- Us was allowed to add their signage instead of demolishing the sign. That agreement ran until 2022 or until Toys-R-U goes bankrupt. As of March 2025, Toys-R-Us will close and the fate of the sign is once again in jeopardy.

Murder by Milkshake is now a two-episode Cold Case Canada podcast:

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.