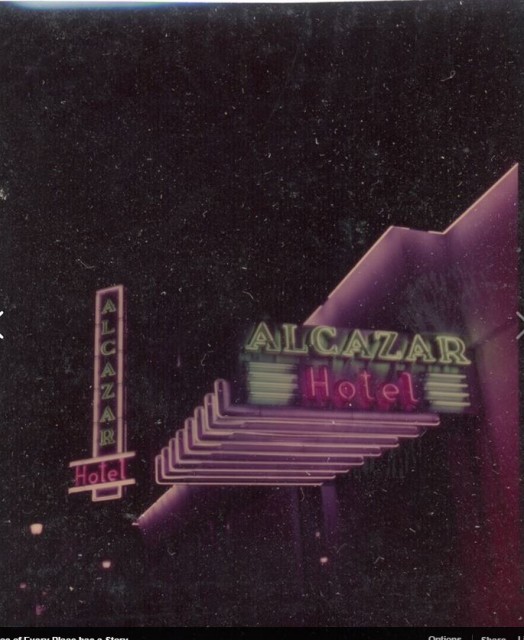

The Melbourne Hotel became No5 Orange in 1971, after 67 years as a hotel and beer parlour

The Melbourne Hotel opened in August 1904 at Westminster Avenue and Powell Street. According to the daily classified ads that ran in the Vancouver Daily World and Province, it had steam heating, electric lights and a white cook. Rates ranged from $1.25 to $1.50 per day with a special rate for long-term boarders.

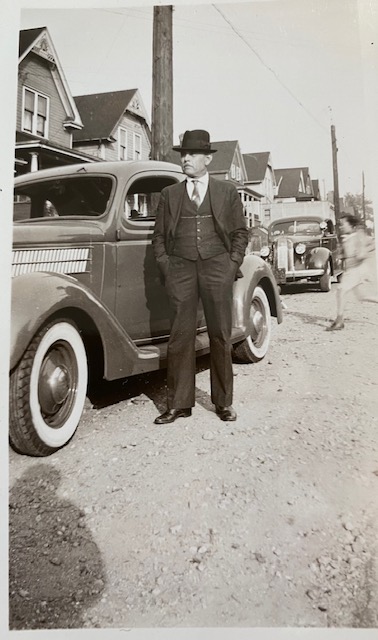

The Brandolinis

Around the time that the Melbourne Hotel* was establishing itself in the city, Leone Brandolini arrived in Vancouver. He bought a house at 507 Prior Street, took labouring jobs, and became a bootlegger during BC’s Prohibition (1917) and later during US Prohibition (1920-1933). He moved into rum running competing against Daniel Joseph Kennedy for marketshare.

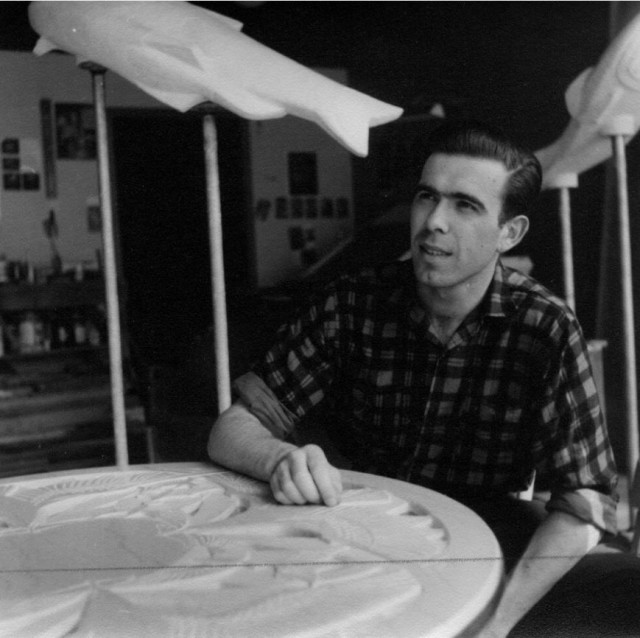

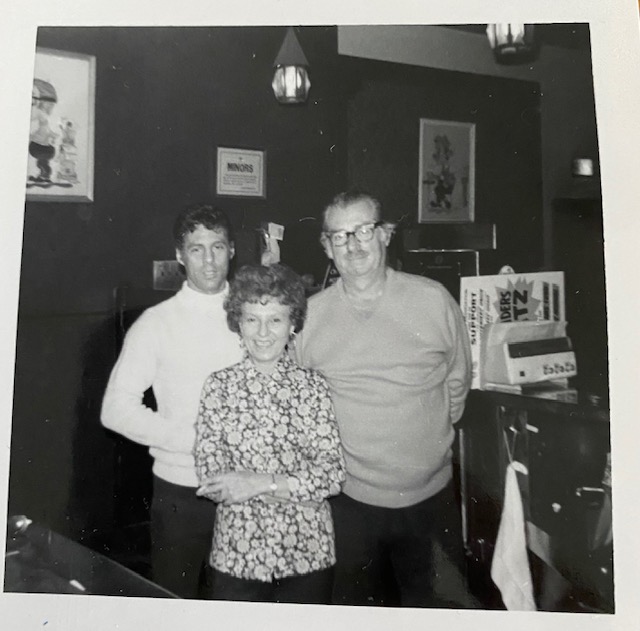

Leone’s son Goliardo (Gillie) eventually joined the family business, married Ermie (sister to the legendary street photographer Foncie Pulice) and they had Leon and Charlene. Younger son Harry arrived 17 years later. Both Leone and Gillie did time at Oakalla prison, but it didn’t slow the family business and Gillie’s sister Elma took baby Charlene out for a walk every day around the East End in a stroller with a false bottom.

“She would take her daily stroll from 507 Prior with Charlene,” says Harry. “Unbeknownst to the law at the time, she was actually making sales of alcohol as well.” Charlene became a popular performer in Vancouver with a star on Granville Street. Gilley made enough money from working at the Columbia Hotel and bootlegging to buy the Melbourne Hotel in 1942. Gillie ran the beer parlour and Elma looked after the rooms.

The Melbourne Hotel

“Pretty well every hotel at that time was built with a beer parlour on the main floor and a few floors of single rooms,” says Harry. “It was literally just a room with a sink and a communal washroom on each floor.” Gillie’s son Leon went to work at the family hotel, and Harry started working the nightshift as a teen in the late ‘60s. After high school he worked in the beer parlour.

By the early 1970s, the area had changed and Gillie sold the hotel. “He sold it to a couple of young guys who had made a bit of money in real estate and thought it would be fun to buy a skidrow hotel,” says Harry. “When it came time to do the deal, one of the owners wanted to change the name to something New Orleans style—and he wanted a colour and a number in the name.” He asked Gillie to name his favourite colour –which was orange, and his favourite number. “My dad said that’s easy. He was a huge Yankies fan and Joe Dimaggio wore Number 5.” Leon stayed on to manage the beer parlour and Gillie held the mortgage.

No5 Orange

The new owners painted the building orange, brought in a live DJ and cranked up the rock ‘n roll. It was hugely successful, but by 1973 they were tired of the business, Gillie had passed away and Harry, Leon, Charlene and their mother Ermie bought the building back.

The night business boomed but the place was an empty shell during the day. They tried various ideas to increase business, and then one day Leon checked out the Olympic Hotel in North Vancouver. He noticed that the strippers danced for the lunch crowd and left. “Leon said ‘why are they doing this? They have a place full of people and then they stop the entertainment, Why?”

The Brandolinis called a family meeting and voted to turn the No5 into a daytime strip club. “Leon’s hand went up, Charlene’s hand went up, my Mum’s hand went up, and I got outvoted,” says Harry.

Strip Club

Charlene’s husband James Hibbard, a choreographer from Los Angeles, worked with the strippers during the day and live music continued at night. No5 went under renovation in 1976 and Harry brought in the R&B Allstars to play weekends. It was a big hit, but after a year or so the competition from nearby hotels started to affect business and the line ups outside the building were no longer. “We decided to flip the switch and go full time with the dancers, from 11 in the morning to 1 a.m.,” says Harry. “We created a really great business and treated everybody with respect. If we hired you, you became part of the family. The dancers felt very safe at No5.”

The Brandolini’s bought the Brass Rail Pub in Coquitlam and sold the No5 in 1981—after nearly forty years as a family business. Leon died in 2012, and his son Dean is now the keeper of the family’s colourful history.

*Being from Melbourne, Australia I was intrigued how and why the Melbourne Hotel got its name. The Brandolini’s don’t know, and according to Changing Vancouver, the first owners Donald McRae and Elizabeth McCannel are from Ontario.

Related:

- Iaci’s Casa Capri

- Bernie Smith and the Penthouse

- Foncie’s North Vancouver Connection

- That House on Yale Street

- 446 Union Street

- © Eve Lazarus, 2022