In July 2016, several large cardboard boxes filled with photographs, clippings, forensic samples, and case notes pre-dating 1950, and thought to be thrown out decades ago, were discovered in a garage on Gabriola Island. They form the basis of Blood, Sweat, and Fear: the story of Inspector Vance, Vancouver’s first forensic investigator.

Crime Scene:

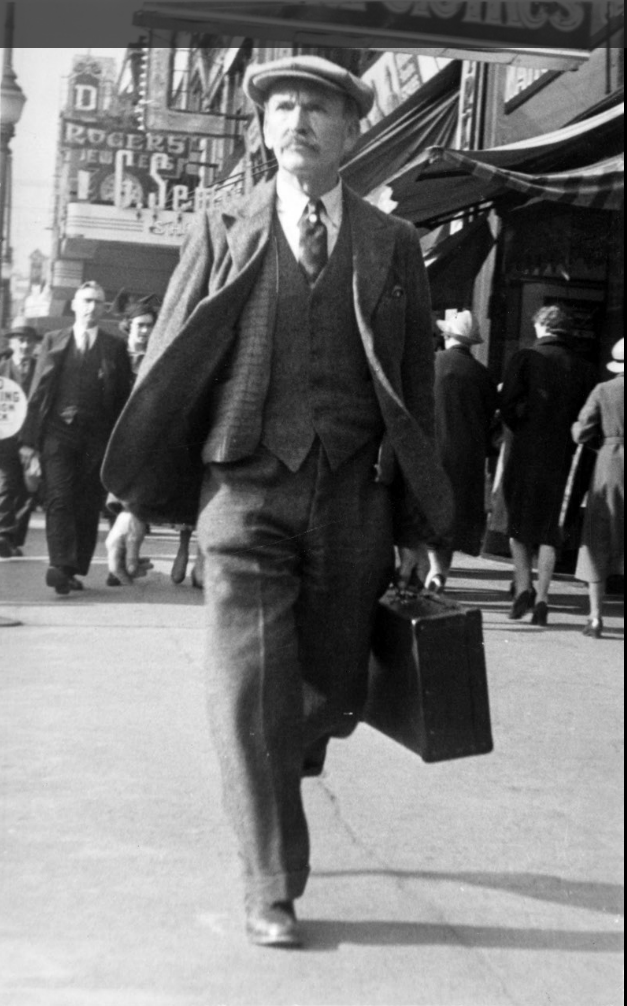

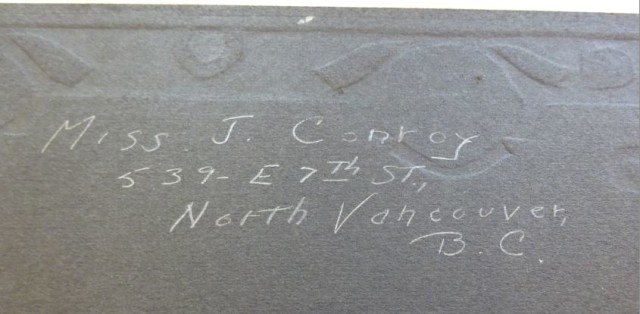

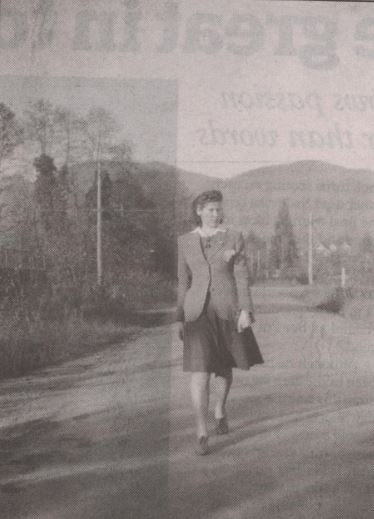

I first “met” Inspector John F.C.B. Vance when I was writing Cold Case Vancouver. He turned up at a crime scene in Chapter 1, the murder of Jennie Eldon Conroy, a 24-year-old war worker who was beaten to death and dumped at the West Vancouver Cemetery. It turned out that Vance wasn’t actually a police officer–he ran the Police Bureau of Science for the Vancouver Police Department, and his cutting-edge work in forensics solved some of the most sensational cases in the first half of the last century.

Unfortunately, Jennie’s wasn’t one of them.

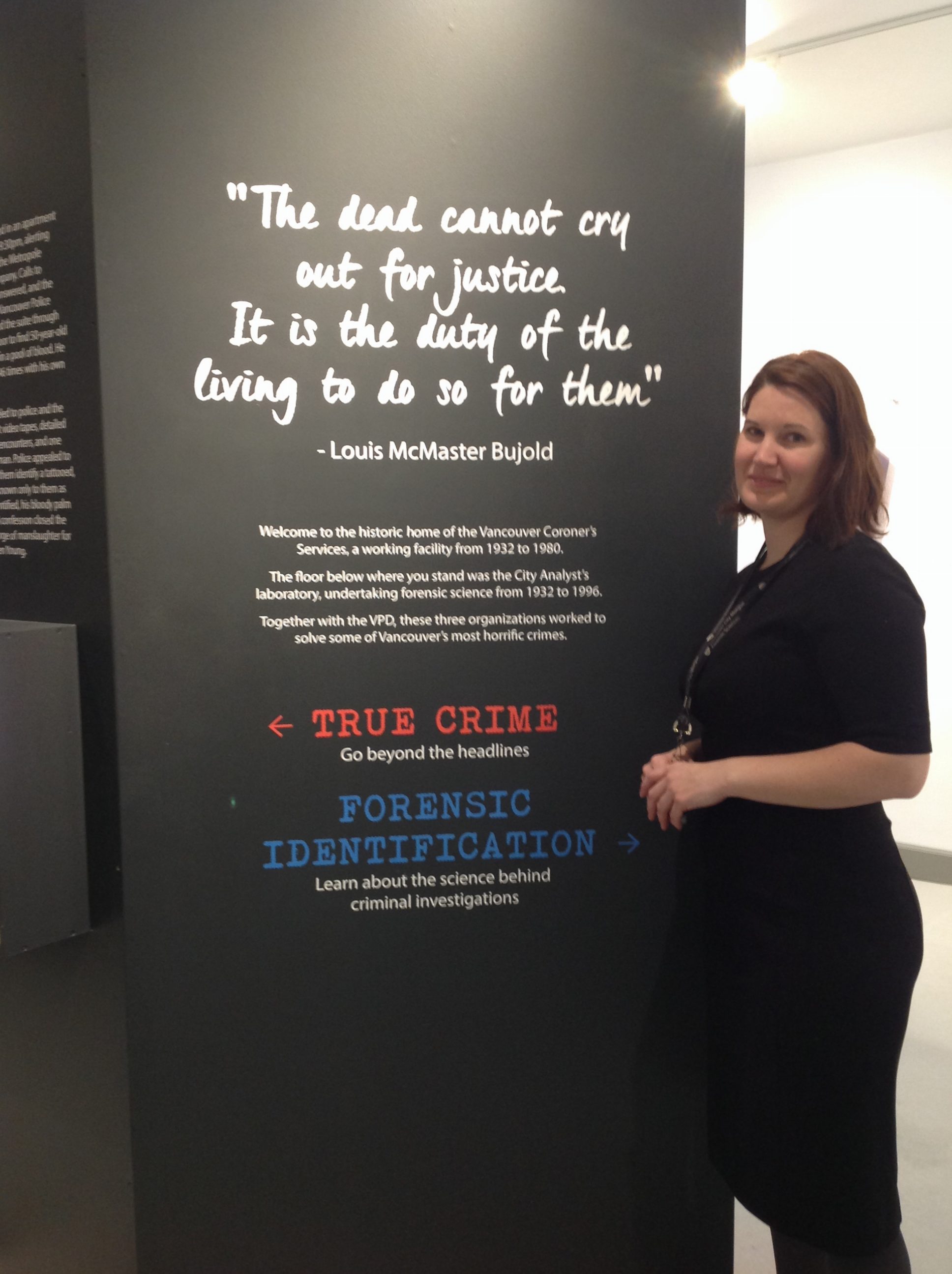

240 Cordova:

For most of his career, Vance worked out of 240 East Cordova Street, the building that now houses the Vancouver Police Museum. With their help, I was able to track down a couple of Vance’s grandchildren. Janey and David remembered that J.F.C.B.—as Vance was known in the family—had packed up several cardboard boxes full of photographs, clippings, and case notes from dozens of cases when he retired in 1949. He took them with him when he moved in 1960, but no one had seen them for years, and it was thought that they’d been thrown out. And then, in July 2016, more than half a century after Vance’s death, the boxes were found in another grandchild’s garage on Gabriola Island.

Jennie Conroy:

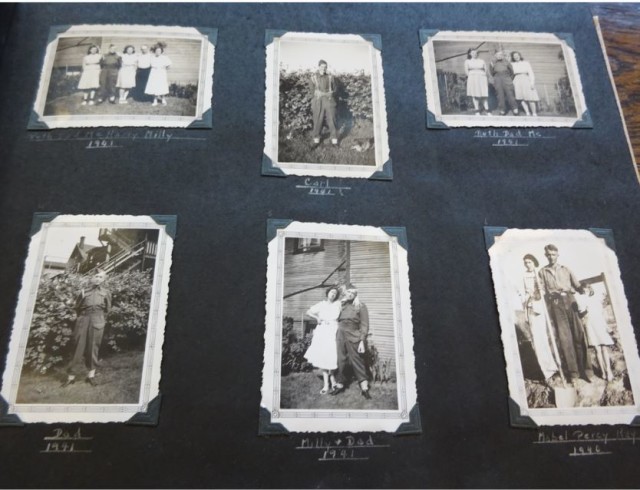

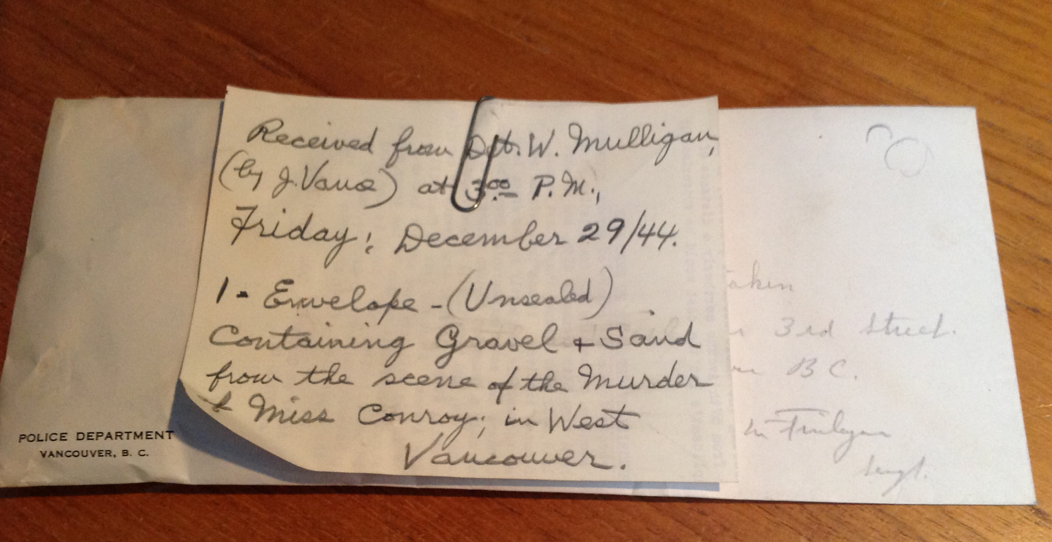

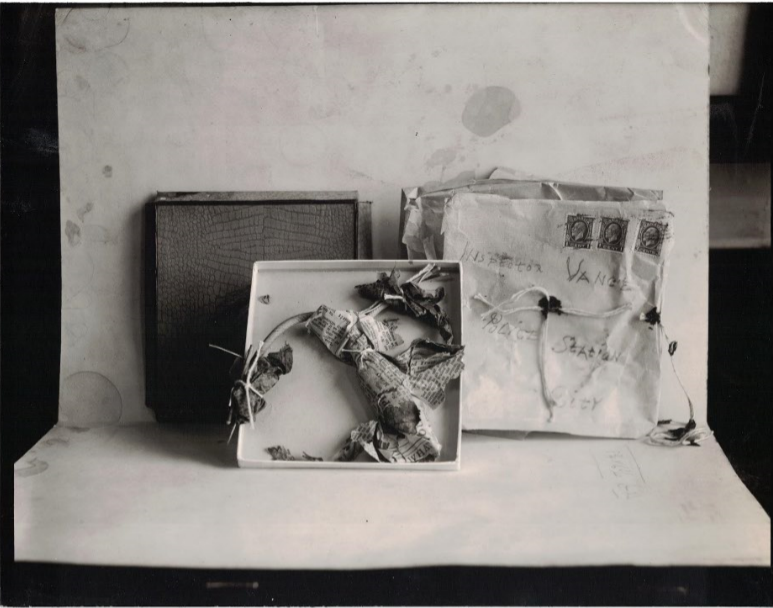

Incredibly, when Janey opened the first box she found a large, tattered envelope labelled Jennie Eldon Conroy murdered West Vancouver, Dec 28, 1944. Inside there were smaller envelopes marked with the VPD insignia and filled with hair and gravel samples from the crime scene, an autopsy report, crime scene photos, and several newspaper clippings.

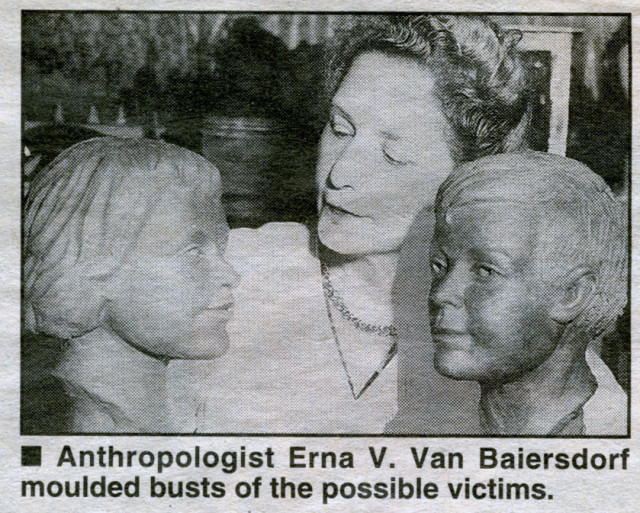

Vance was skilled in serology, toxicology, ballistics, trace evidence and autopsy. He was a familiar face at crime scenes and in the courtroom, and was called the Sherlock Holmes of Canada by the international media. Yet few people have heard of him.

Hopefully that will change with the publication of Blood, Sweat, and Fear, but best of all, all those boxes, the crime scene photos, the case notes, even Vance’s personal diary, are now with the Vancouver Police Museum and Archives. They’ll be properly processed, cared for, and eventually made available to the public.

Related: Blood, Sweat and Fear: A True Crime Podcast

Blood, Sweat and Fear: The Story of Inspector Vance is now a 12-episode True Crime podcast

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.