A few months back, I spent a frustrating hour searching for a plaque at the corner of West Hastings and Hamilton Streets. It was unveiled in 1953, as evidenced in a Vancouver Sun article and photo.

It wasn’t there.

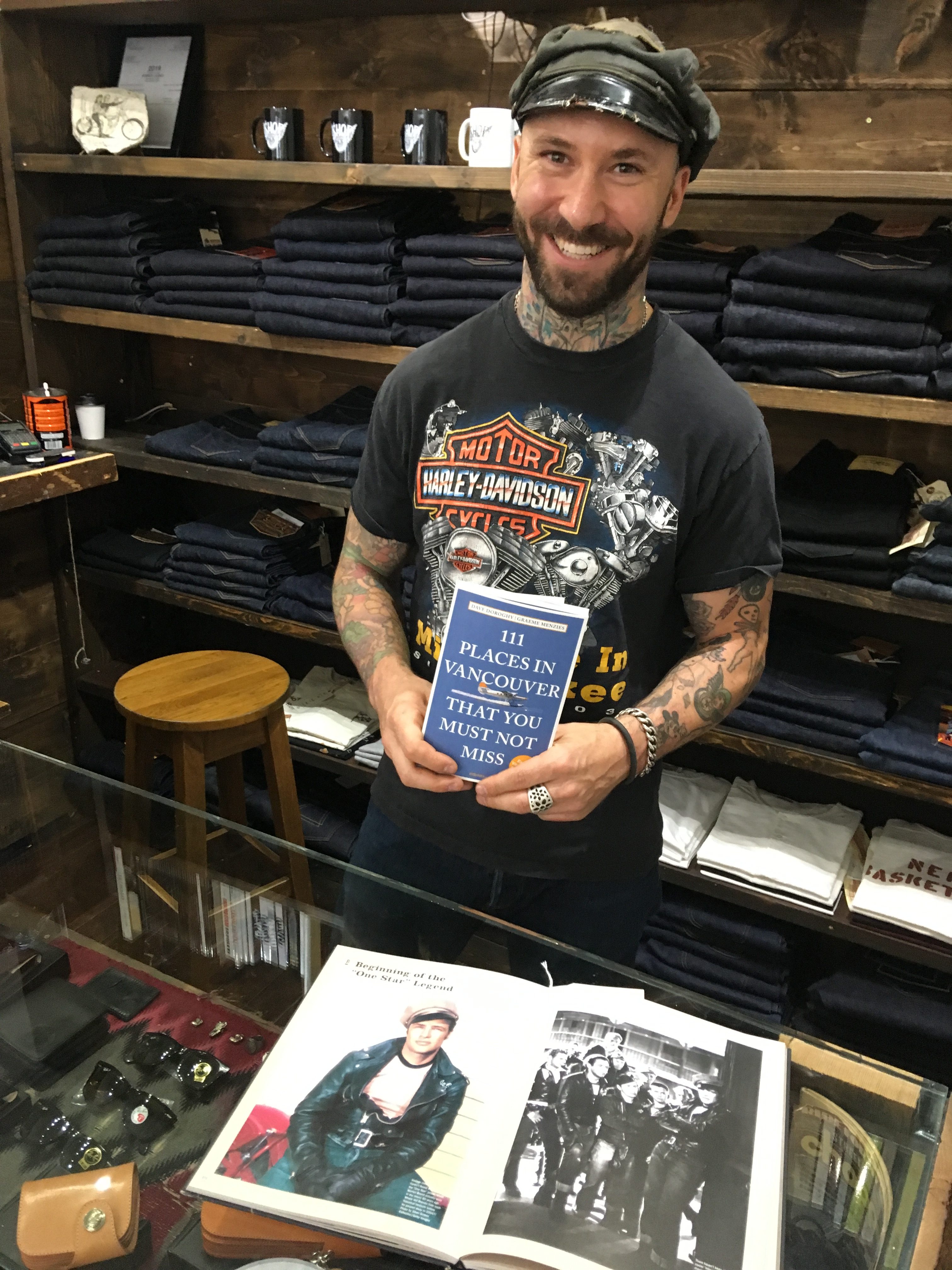

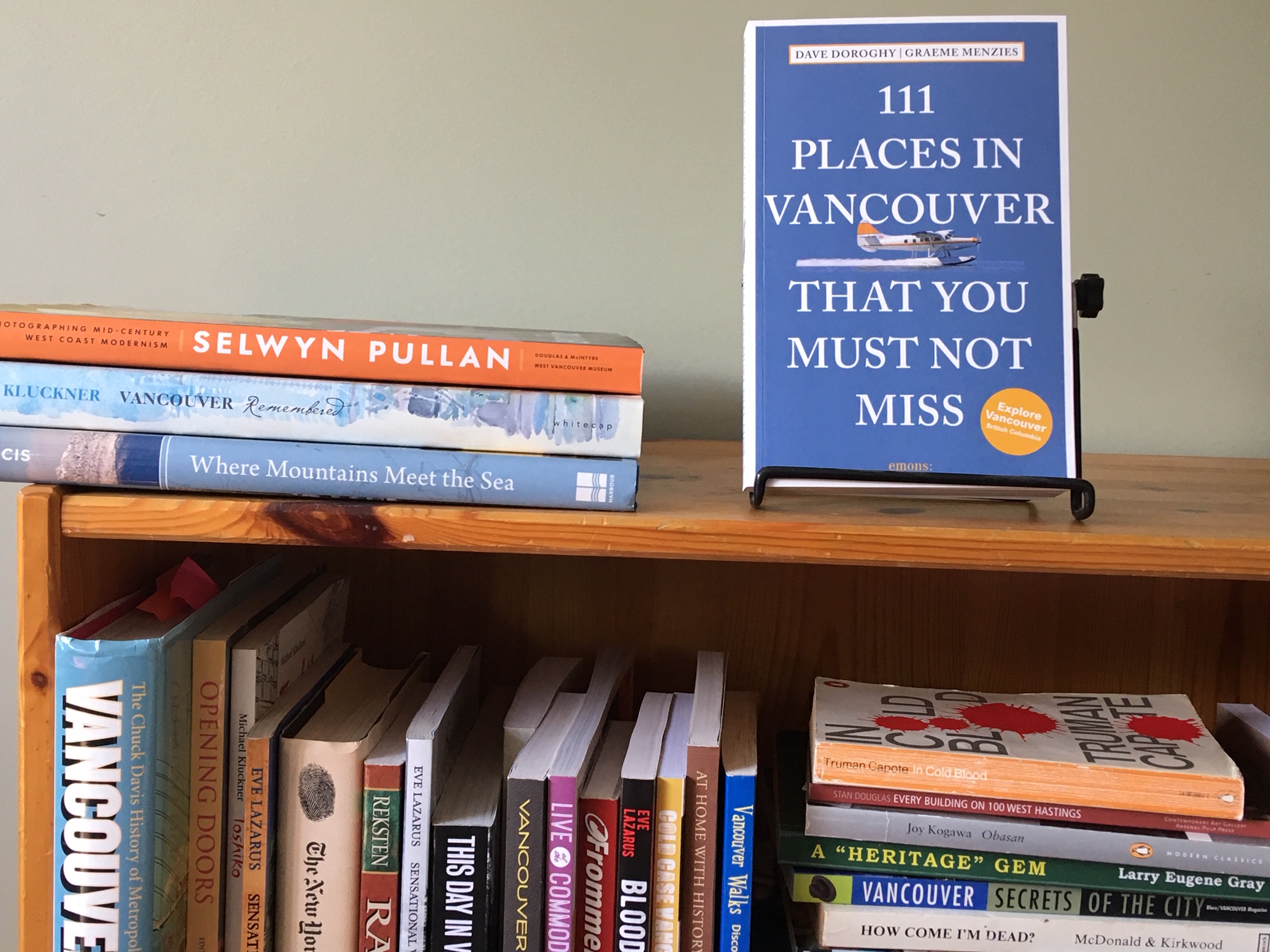

Graeme Menzies, co-author of 111 Places in Vancouver that you Must Not Miss, tells me he did the same thing while researching his book and it’s entry #41: “Hamilton’s Missing Plaque.” Turns out it was taken down about five years ago when the CIBC building was demolished and it was never replaced. I suspect no one wanted to advertise that a white dude called Lauchlan Hamilton named streets after himself and his railway pals.

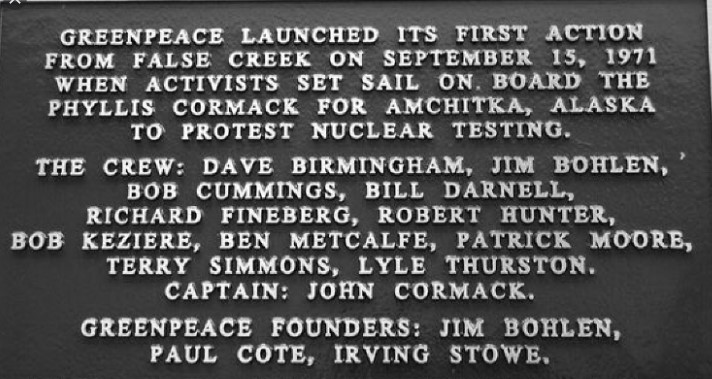

One plaque you can see is entry #37—the Greenpeace Plaque. It tells the story of the crew of 12 setting sale for Alaska from False Creek on September 15, 1971.

Graeme met his co-author Dave Doroghy when the two worked at the Vancouver 2010 Olympics. Graeme looked after the official publications and digital communications, while Dave was director of Sponsorship sales. They bonded over a love for history and quirky Vancouver stories.

“I am a bit of a history buff and in another life would have enjoyed being an archeologist, so peeling back the layers about a place to find something new really rings my bell,” says Graeme. “I enjoyed learning about the Toys R Us sign on West Broadway and finding the original Fluevog store was very rewarding. The Billy Bishop pub is another favourite—it’s one of those places that is so different on the inside that you wonder if the doorway isn’t really some sort of Alice-in-Wonderland portal to another world.”

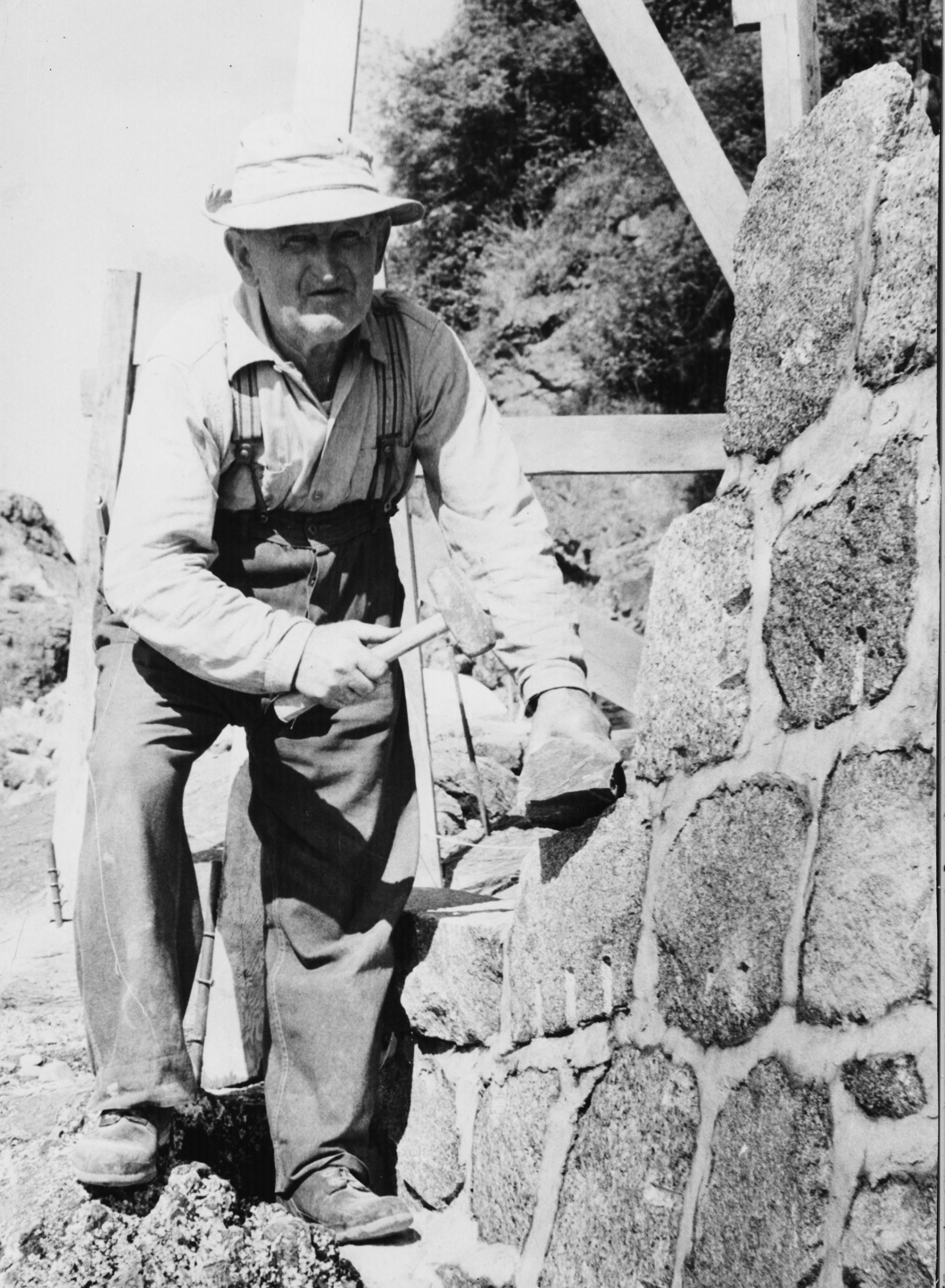

I’ve written a lot about Jimmy Cunningham over the years—he’s the guy who built most of the Seawall—but until I read this book, I didn’t know that there were symbols—a hockey puck, hockey stick, the four card suits and a maple leaf—carved into the stones of the wall near Third Beach.

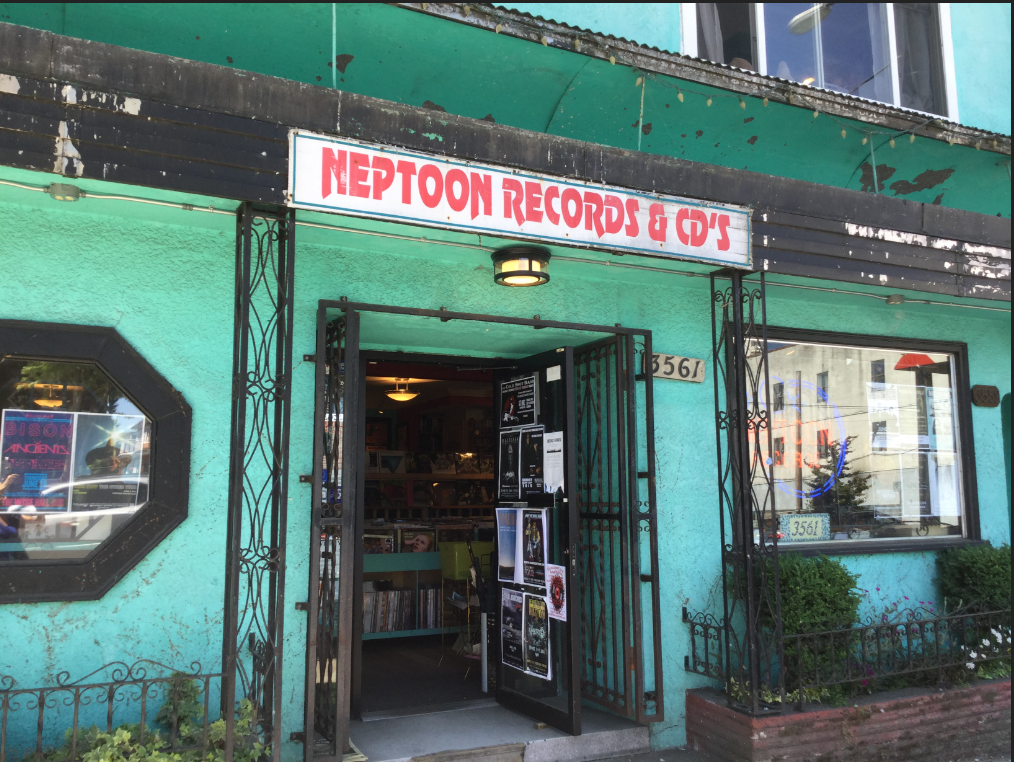

You’ll also find some very Vancouver-type businesses such as Lotusland Electronics that sells things like vintage stereo turntables and vertical record players on Alma Street in Kitsilano; and there is Cartem’s on Main Street, a donut shop inside a 1912 building. Just up the road a bit Rob Frith’s Neptoon Records, still does a roaring trade in vinyl.

The good news is that many of our indie bookstores are open for online orders and curbside pick up. For instance, the Book Warehouse is offering a flat $5 delivery fee anywhere in the Lower Mainland. Check out this map for bookstores that deliver near you or offer curbside pickup, and thanks for supporting local bookstores, local publishers and local authors like me.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.