Those of us who write history books are used to being told “my dad would love that.” And while hearing things like this warms our hearts; it’s nice to think that our books are finding a wider audience.

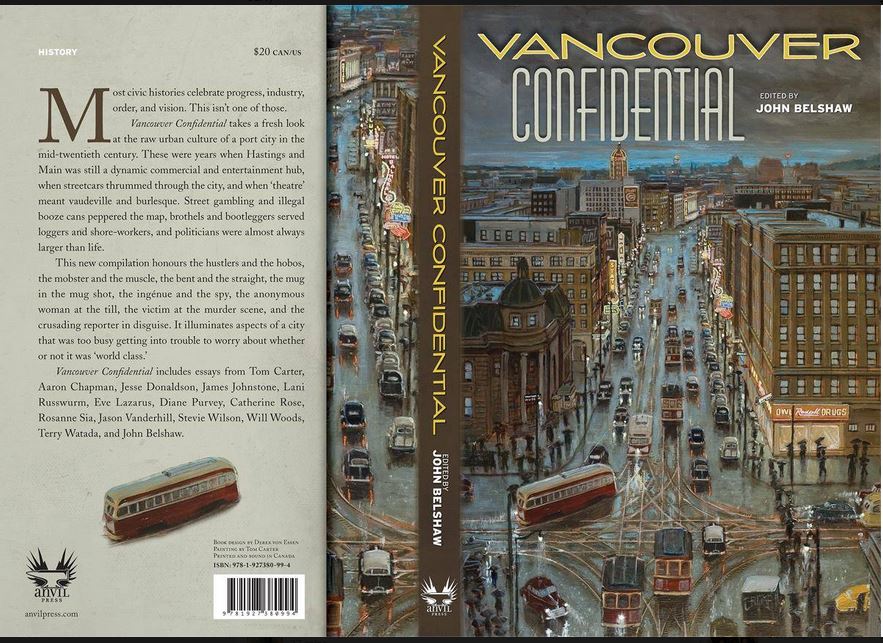

I reckon John Belshaw has nailed it with Vancouver Confidential, a book that should appeal to all demographics and interests. As John writes “most civic histories celebrate progress, industry, order and vision. This isn’t one of those.”

I’m proud to be one of the 14 contributors to this book. My colleagues are academics, writers, artists, tour guides and musicians, all drawn together by a fascination for obscure facts and ephemera, and a love for non-traditional history.

It’s my pleasure to introduce three of our young and talented contributors: Catherine Rose, Rosanne Sia and Stevie Wilson.

Cat Rose is a crime analyst with the Vancouver Police Department who moonlights as a Sins of the City tour guide. It’s a dual role that gives her a unique insight into Vancouver’s underbelly. Her chapter “Street Kings; the dirty ‘30s and Vancouver’s unholy trinity” features a corrupt chief of police and two of Vancouver’s most notorious criminals.

“When I was digging through our files at the Police Museum one day, I found some long lost documents pertaining to an internal enquiry in 1935,” she says. “There’s a perception in society that “the Thin Blue Line” protects even the most corrupt police officers from facing justice, but I thought it was really interesting to see how corruption was perceived by members of the Vancouver police themselves back in the 1930s and how many officers were willing to rat out their brothers to try and put a stop to it.”

Before moving to L.A. to work on her doctorate in American Studies and Ethnicity, Rosanne Sia taught English

in Paris, worked as a storyteller for the Vancouver Dialogues Project, as a researcher for the Visible City project, and worked on the Hope in Shadows calendar with Pivot Legal Society in the DTES.

Rosanne’s chapter describes a 1937 murder that triggered a ban on white waitresses in Vancouver’s Chinatown, and is punctuated by a Vancouver Sun photo of 15 waitresses on a protest march from Chinatown to Vancouver City Hall.

“What is so remarkable about these young women is that through their personal experience working in Chinatown they had learned to see issues around race and ethnicity in a different way than almost every other Caucasian in Vancouver,” she says. “I loved their determination and the brazen attitude they displayed to the authorities.”

At 26, Stevie Wilson is the youngest of our group, but she already has a formidable resume. Stevie is a columnist for Scout Magazine, and she wrote and co-produced Catch the Westbound Train, a documentary that aired on the Knowledge Network in August and has already notched up a slew of awards. The film and Stevie’s chapter drops us into the Vancouver of 1931, where hobo jungles sprang up to house the homeless men who poured into the city looking for work.

“I stumbled upon a few archival photos of the hobo jungles while doing research for a column and was immediately both confused and curious. Who were these men who had constructed these small shelters with their bare hands? More importantly, why had I never heard about them?” she says. “I felt this subject was something that Vancouverites should know about, and that the story of these men provides a few thoughtful parallels to our own modern issues of homelessness and unemployment.”

The book launch for Vancouver Confidential kicks off at 6:00 p.m. Sunday September 21 at the Emerald Supper Club in Chinatown.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.