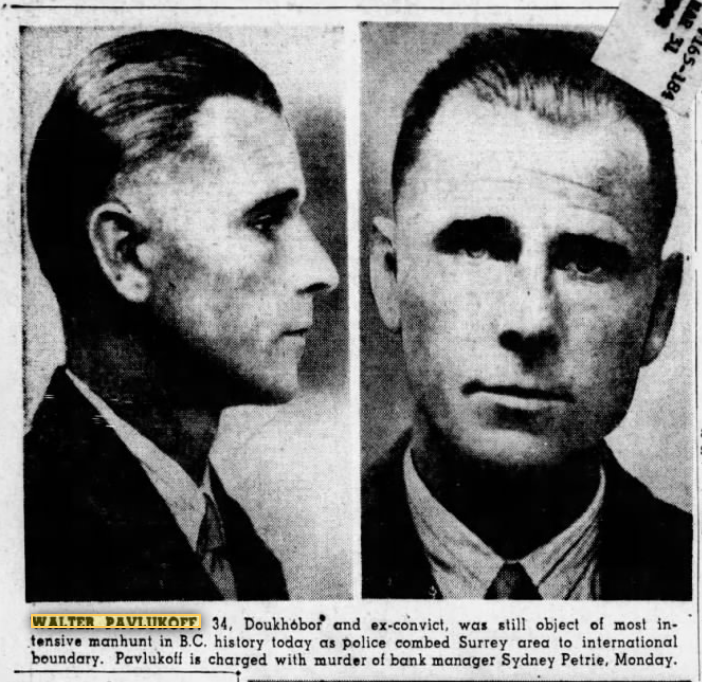

Walter Pavlukoff stepped out of his hotel room on August 25, 1947 and joined the PNE parade. Then he robbed a bank and murdered the manager.

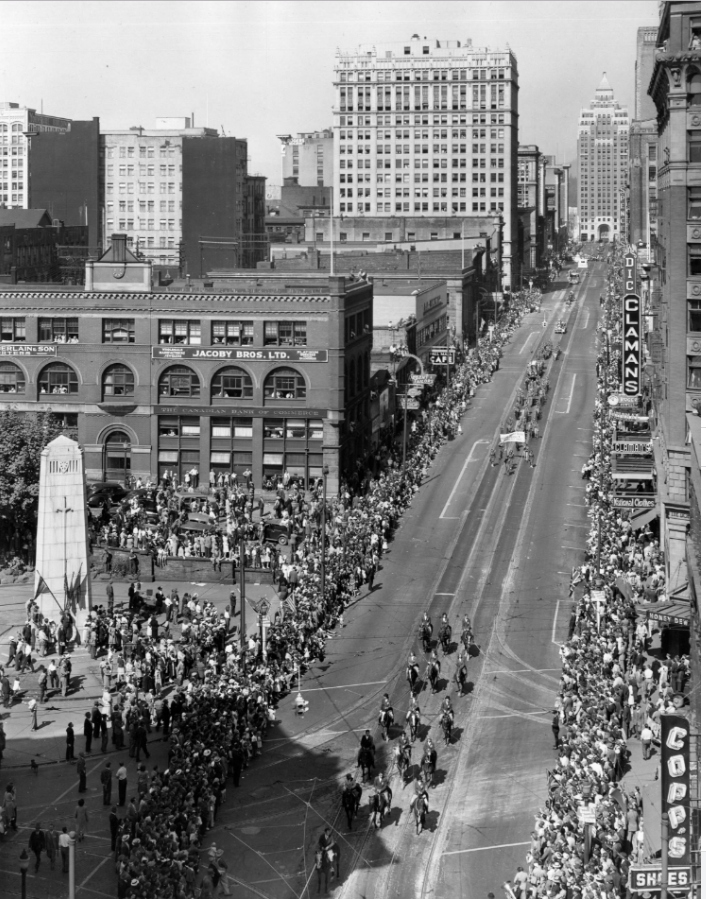

PNE Parade

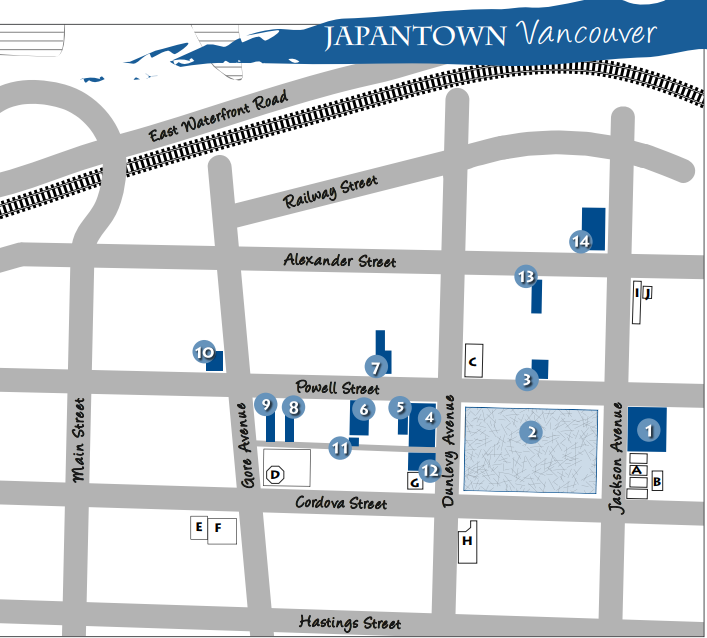

On August 25, 1947, 34-year-old Walter Pavlukoff stepped out of his hotel room on East Cordova Street in Vancouver with a luger automatic pistol in his pocket. He joined over 100,000 people who were watching the Pacific National Exhibition parade—the first one in six years because of the war.

Walter then crossed the bridge to Kitsilano, bought a paper bag and a newspaper from a grocery store and proceeded to hold-up the CIBC on West Broadway (at MacKenzie).

CIBC Bank:

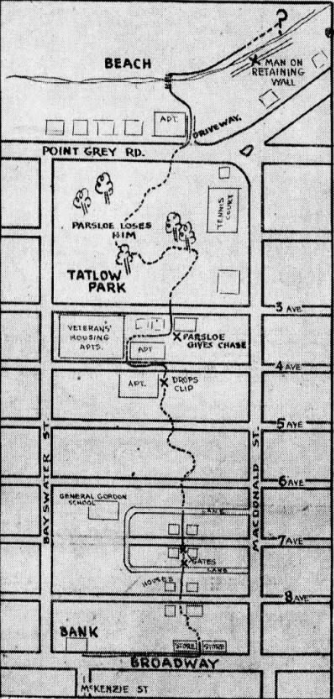

It was shortly before closing time and the bank was full of customers. Walter managed to shoot and kill the bank manager, before fleeing the bank empty-handed and pursued by half a dozen civilians and a police officer who happened to be sitting outside.

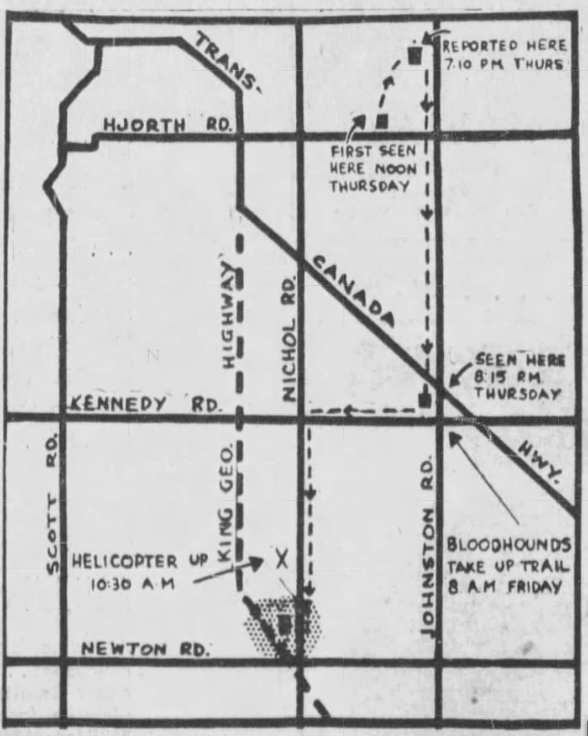

Walter managed to escape the roadblocks that were thrown up around Kitsilano, and didn’t come to police attention again for three days. A prison guard from Oakalla, where he had spent time, recognized him robbing the eggs from his Surrey farm.

On the run:

Armed police from all over Metro Vancouver converged in Surrey armed with rifles, automatics, sub machine guns, sawed-off shotguns and tear gas. It was early days for communications, so police borrowed walkie-talkies from the PNE to use for on-the-ground communication, and 200 hunters, trappers and other civilians joined in the chase. It was the largest manhunt in Vancouver’s history.

You’ll be surprised how far he got, how long he evaded police, and how he was eventually caught.

Show Notes

Credits:

- Intro and outro music: Duke Ellington’s St. Louie Toodle

- Intro: Mark Dunn

- Words of Walter Pavlukoff voiced by Matthew Dunn

- Background track created by Nico Vettese

- Outro: Audionetwork.com

Sources:

- Blood, Sweat, and Fear: The Story of Inspector Vance, Vancouver’s First Forensic Investigator, by Eve Lazarus (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2017)

- Angelo Branca: Gladiator of the Courts, by Vincent Moore (Douglas and McIntyre, 1981)

- Inquest for Sidney Petrie (BC Archives)

- Vital Statistics

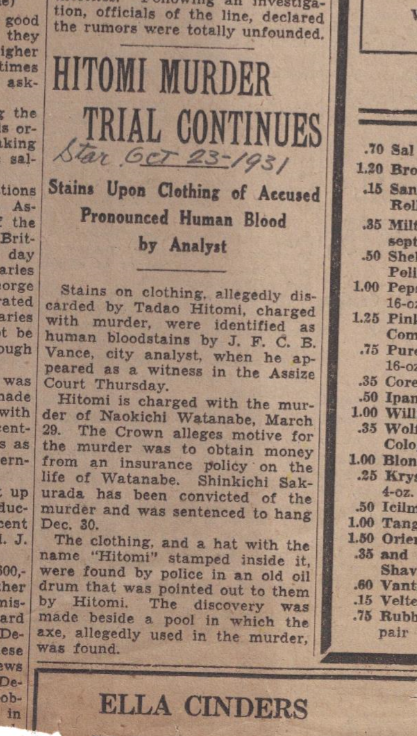

- The personal files of Inspector John F.C.B. Vance

- Newspapers: Vancouver Sun, Province, Vancouver News Herald, Calgary Herald, Lethbridge Herald, Globe & Mail

Featured Promo: Dark Poutine True Crime and Dark History