Harry Jerome and Percy Williams were two of the most remarkable sprinters in Vancouver’s history.

This story is from Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

Former Province sports reporter Brian Pound tells me that the first time the two officially met was at a photo shoot that he had set up at a clothing store near the insurance office where Percy worked. “Harry broke Percy’s long time 200 yard record and just missed his 100 yard mark,” says Brian. “The photo of the two of them was taken by famed Province photographer Bill Cunningham. They are holding my story of the meet.”

Harry breaks record:

Harry broke Percy’s 200-yard mark set three decades ago at the 1959 Vancouver and District Inter-High meet.

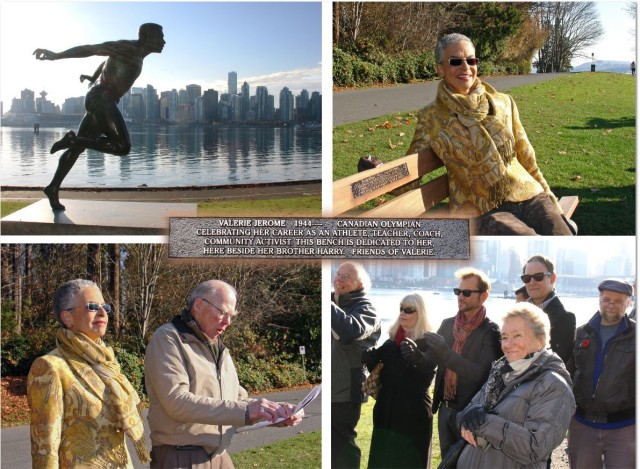

Harry is well known—his name adorns recreation centres and his statue is in Stanley Park. And at one time he was the fastest man alive, setting a total of seven world records, Percy, who before Harry came along was the fastest man alive, remains a bit of an enigma. In these days of super-charged Olympic athletes, he was truly unique.

Grew up in Mount Pleasant:

Percy Williams was born in 1908 and spent a good chunk of his life on West 12th Avenue in Mount Pleasant. He was a scrawny kid, standing just 5’6” and weighing 110 pounds. He had a bad heart from childhood rheumatic fever

Percy’s coach, Bob Granger, told a reporter that he took Percy on after he tied a race with his sprint champion in 1926. “It violated every known principle of the running game,” he said. “He ran with his arms glued to his sides. It actually made me tired to watch him.” Granger had interesting training techniques. His idea of a warm-up was having Percy lie on the dressing table under a pile of blankets. Another was making him run flat out into a mattress propped up against a wall. Unorthodox maybe, but Percy kept winning.

Brings home Olympic medals:

By 1928, Percy had bulked up to 125 pounds. That was the year he brought home two gold medals for the 200 and 100 metre sprints at the Amsterdam Olympics. The newspapers dubbed him “Peerless Percy,” and he returned to Vancouver to a welcome from 40,000 people. Kids got the day off school and one firm brought out an “Our Percy” chocolate bar.

Percy was a reluctant star, and when a leg injury ended his track career in 1932, he seemed relieved. He told a reporter: “Oh, I was so glad to get out of it all.” By 1935, the public had forgotten all about him, and he soldered quietly on as an insurance salesman.

Percy held onto his record for the 200-metre dash for 32 years—when Harry Jerome set a new record in 1959. The tragedy was both men died in 1982. Harry, 42, from a brain aneurysm just eight days after Percy, suffering from arthritis, shot himself in the head in his West End bathtub.

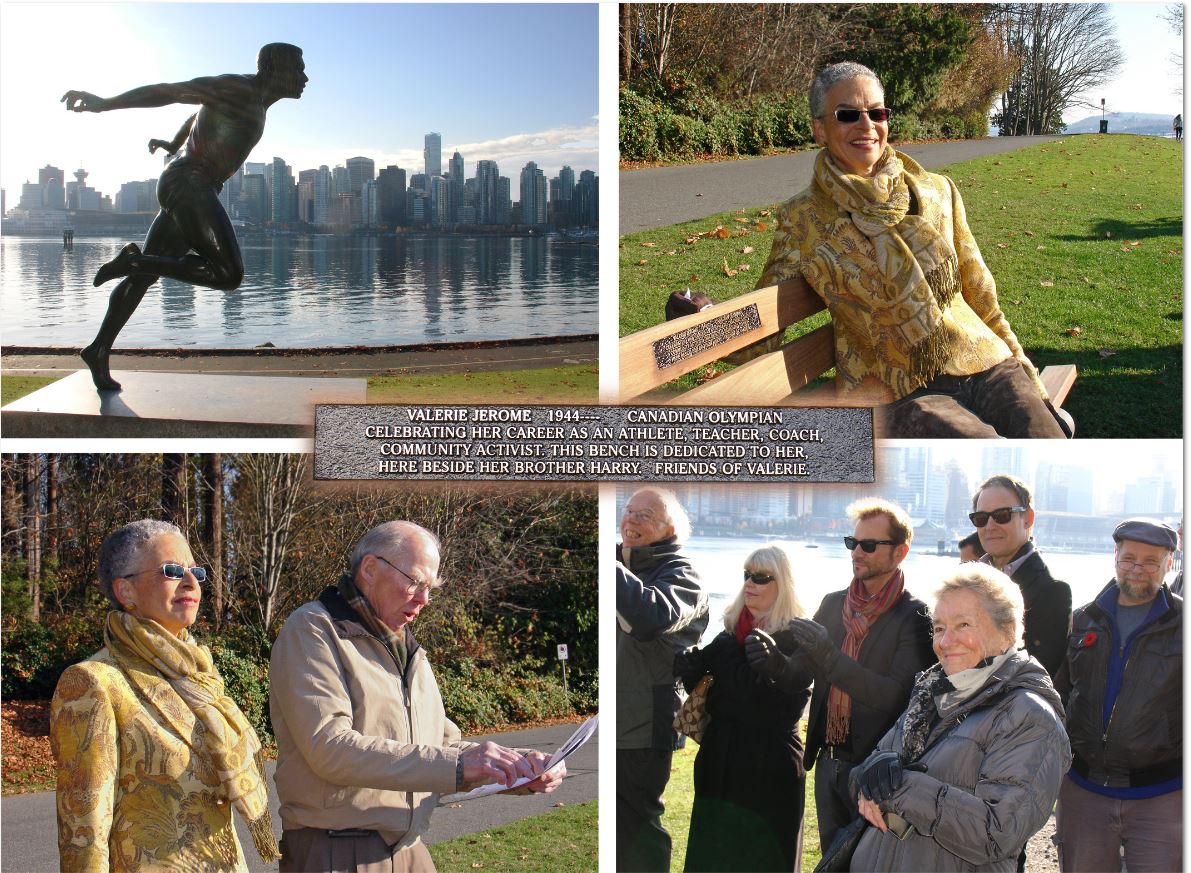

Related: Valerie Jerome: fastest woman alive

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus