At the end of our last post, we were watching harbour seals at Mosquito Creek. Now we’re going to take the Spirit Trail to Harbourside. While you may see a large tract of vacant land, as well as some businesses, a Spa Utopia, and an auto mall–developers see 700 condos, office space, retail stores, and a hotel.

Did you know that all the land at the bottom of Fell Avenue used to be tidal flats? In the late 1800s, James Pemberton Fell and his uncle Arthur Heywood-Lonsdale, bought District Lot 265 which included the foreshore rights. James had lofty goals that included a million-dollar marina and industrial complex. He got as far as building a seawall and creating 21 acres (8.5 hectares) of additional land before the Great War hit and all infrastructure plans were put on hold.

So, over 100 years later, let’s not go counting those condos until they’re hatched.

Back on our bikes we’re going to ride along the waterfront past the off-leash dog park and take a hard right up Kings Mill Walk and the Harbourside West Overpass and onto Pemberton Avenue.

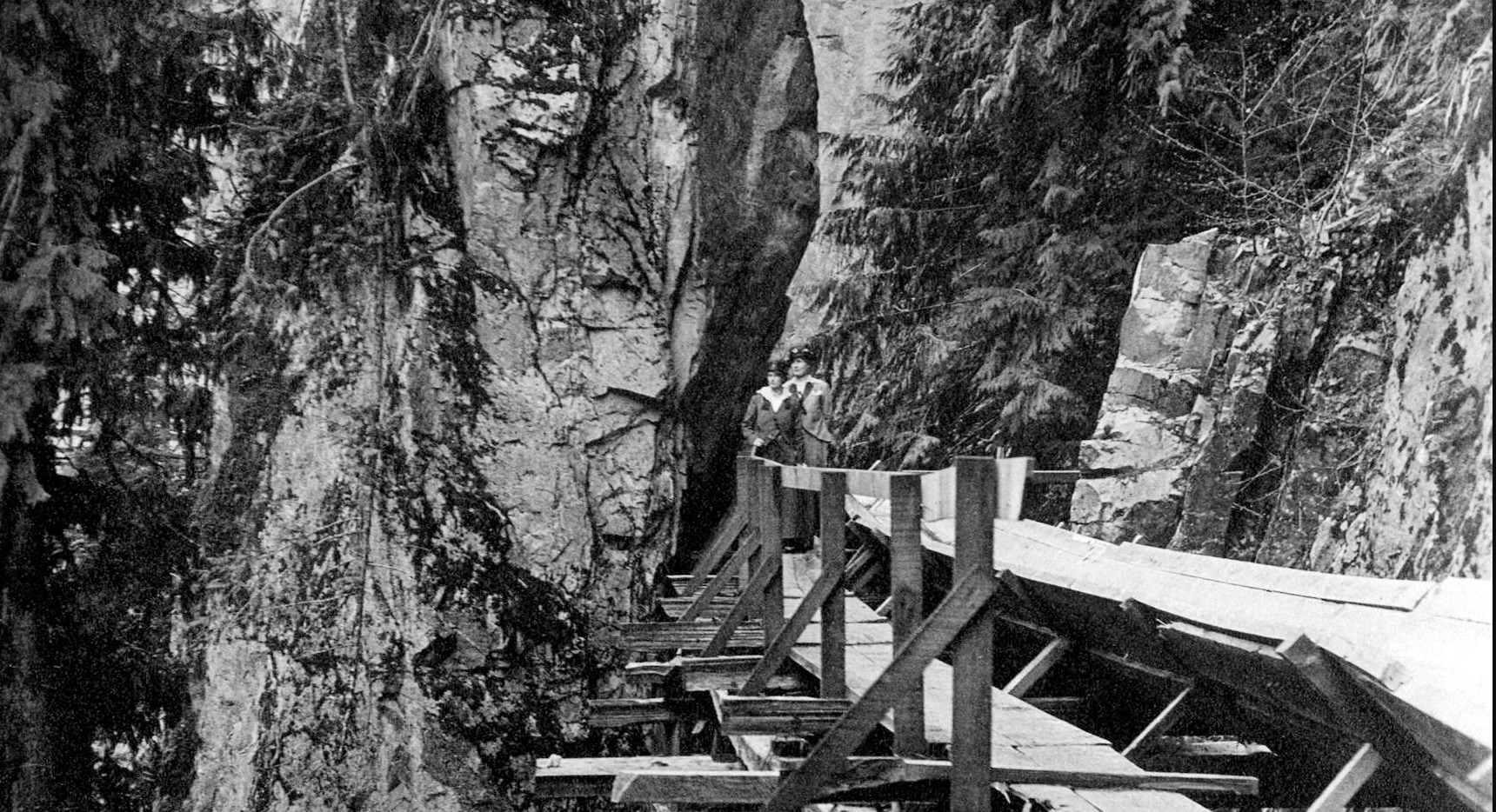

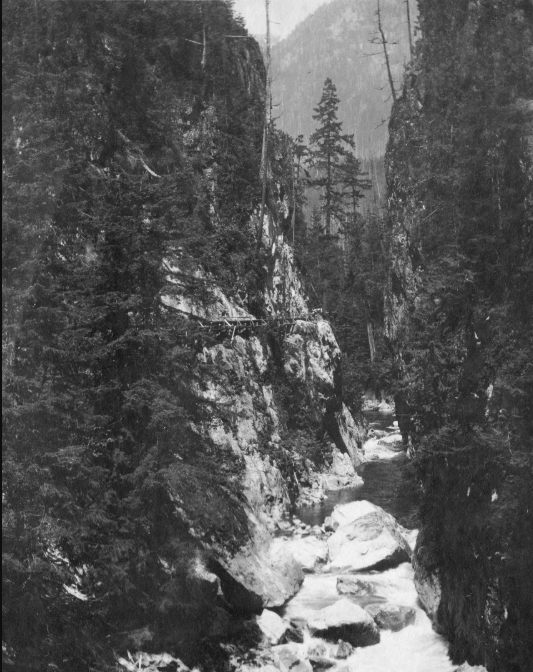

In the early 1900s several different flumes in North Vancouver transported logs and shingle bolts from the forests to the sea. They were long wooden chutes filled with running water, used by loggers like conveyor belts to float cedar shingle bolts from the hills above to the mills below.

The Capilano River flume was the longest at over 12 kilometres in length. Built in 1905, it ran from Sisters Creek, just north of where the Capilano Reservoir is today, to a mill at the foot of Pemberton Avenue. The flume had a catwalk that ran alongside it so crews could do maintenance, but it was also accessible to the public.

In the early part of the 20th century the Capilano Timber Company had its own railway for transporting fir, hemlock and cedar logs from the upper Capilano valley to the firm’s grounds near the foot of Pemberton. The railway ran down the west side of the Capilano River, crossed the river and headed eastward, running along what is now the Bowser Trail behind Save on Foods. The train crossed Pemberton and Marine drive and headed south and lasted until the early 1930s.

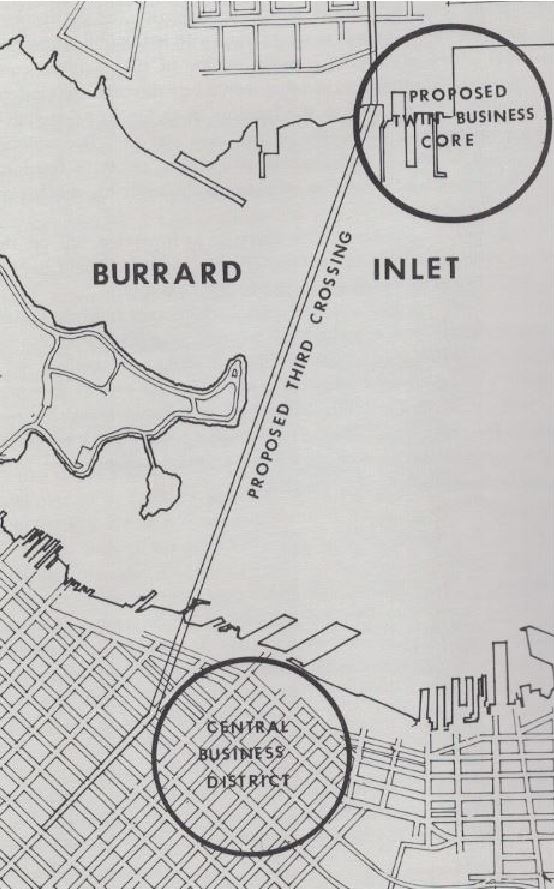

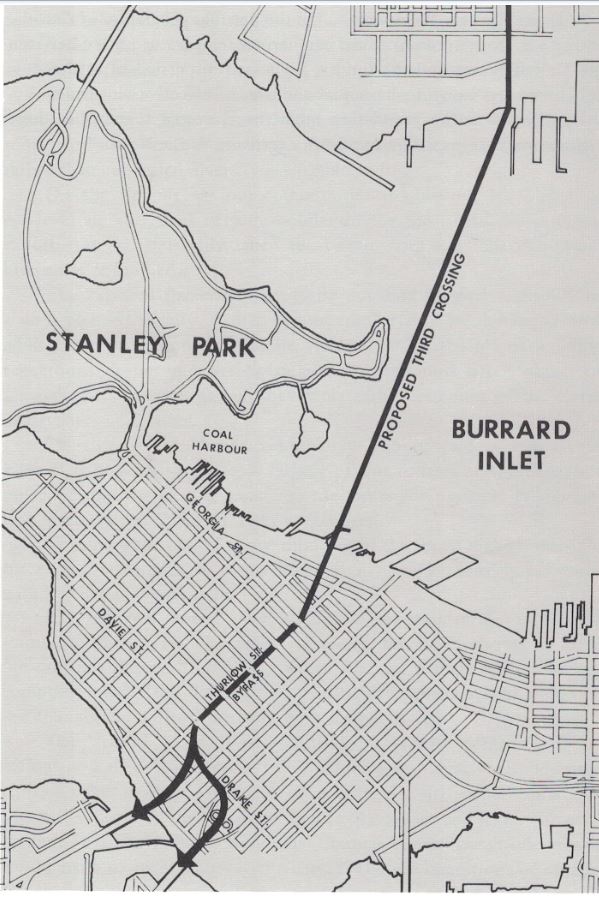

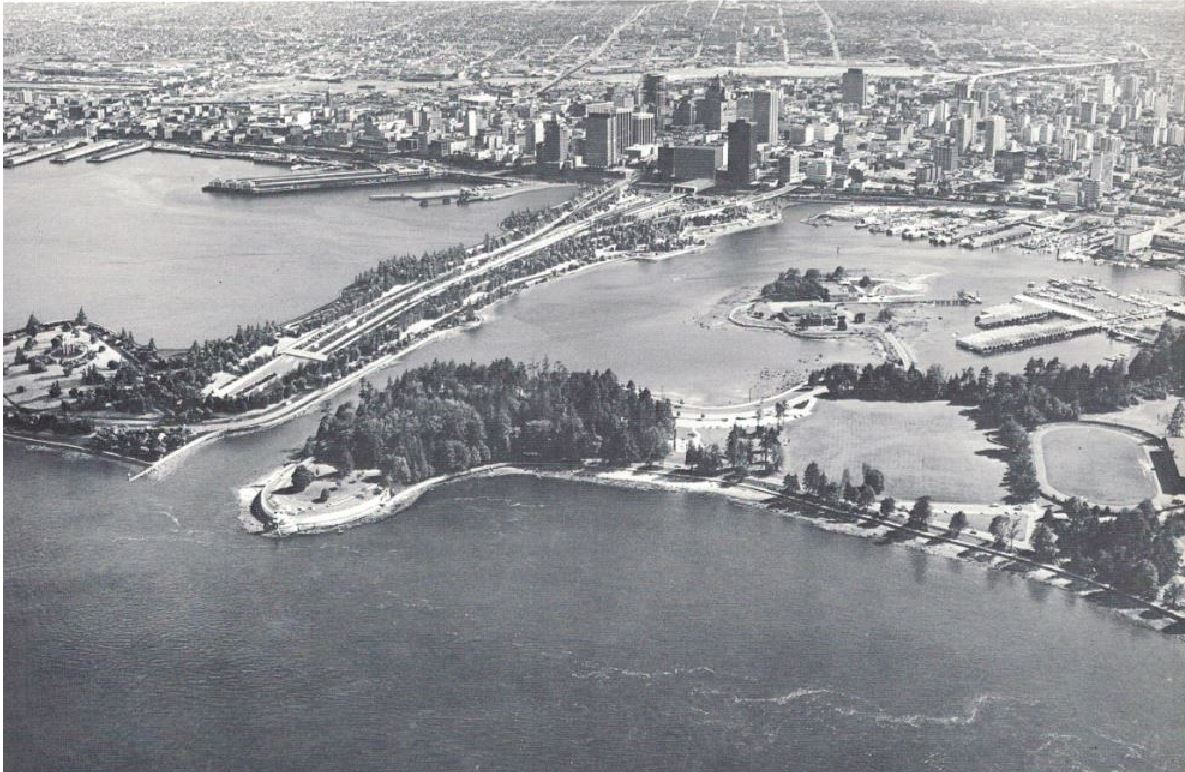

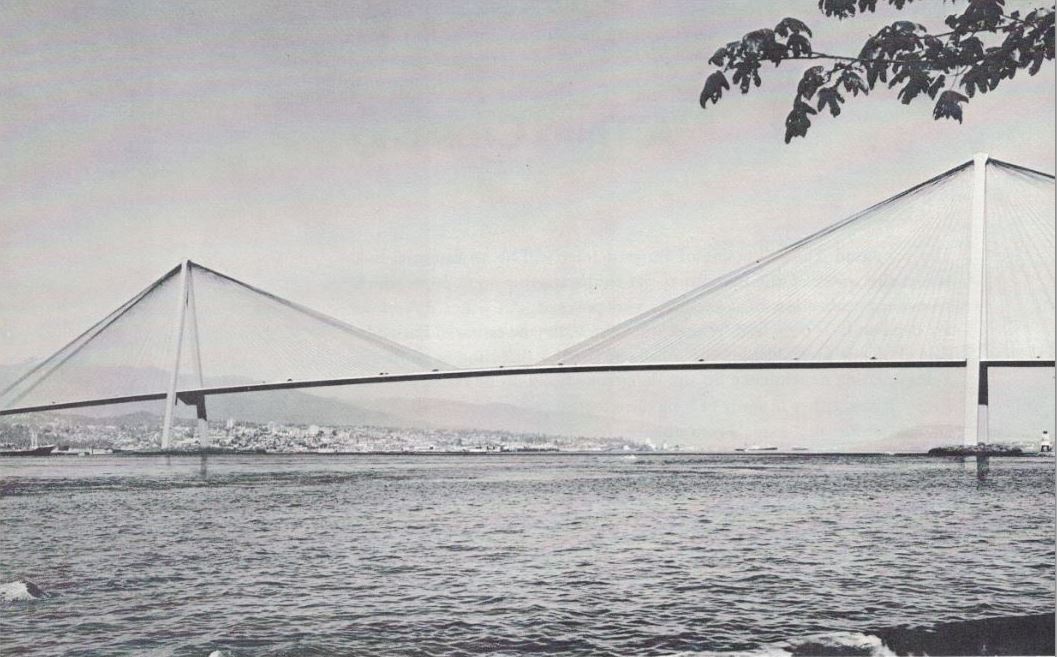

In the 1970s, Pemberton Avenue almost became the jumping off point for the North Shore’s third crossing. Alderman Warnett Kennedy, an architect and town planner lobbied for a tunnel under Thurlow Street that would carry cars and rapid transit to the North Shore over the world’s biggest cable bridge, and exit at Pemberton Avenue.

Instead, you’ll find Vancouver Shipyards and the headquarters of Seaspan, the largest tug and barge company in Canada. After winning a federal government contract in 2011 to build 17 ships that include a Polar-class icebreaker for the Coast Guard, the company built a new office on the western spit of the Seaspan property. Seaspan expects to fill it with more than 1,300 new shipbuilding and office staff by 2020.

Next post we’ll be winding through Norgate to Ambleside.

The North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Moodyville (part 1)

Moodyville to Lonsdale Quay (part 2)

Pemberton to Capilano River (part 6)

- Top sketch: from Concert developers

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.