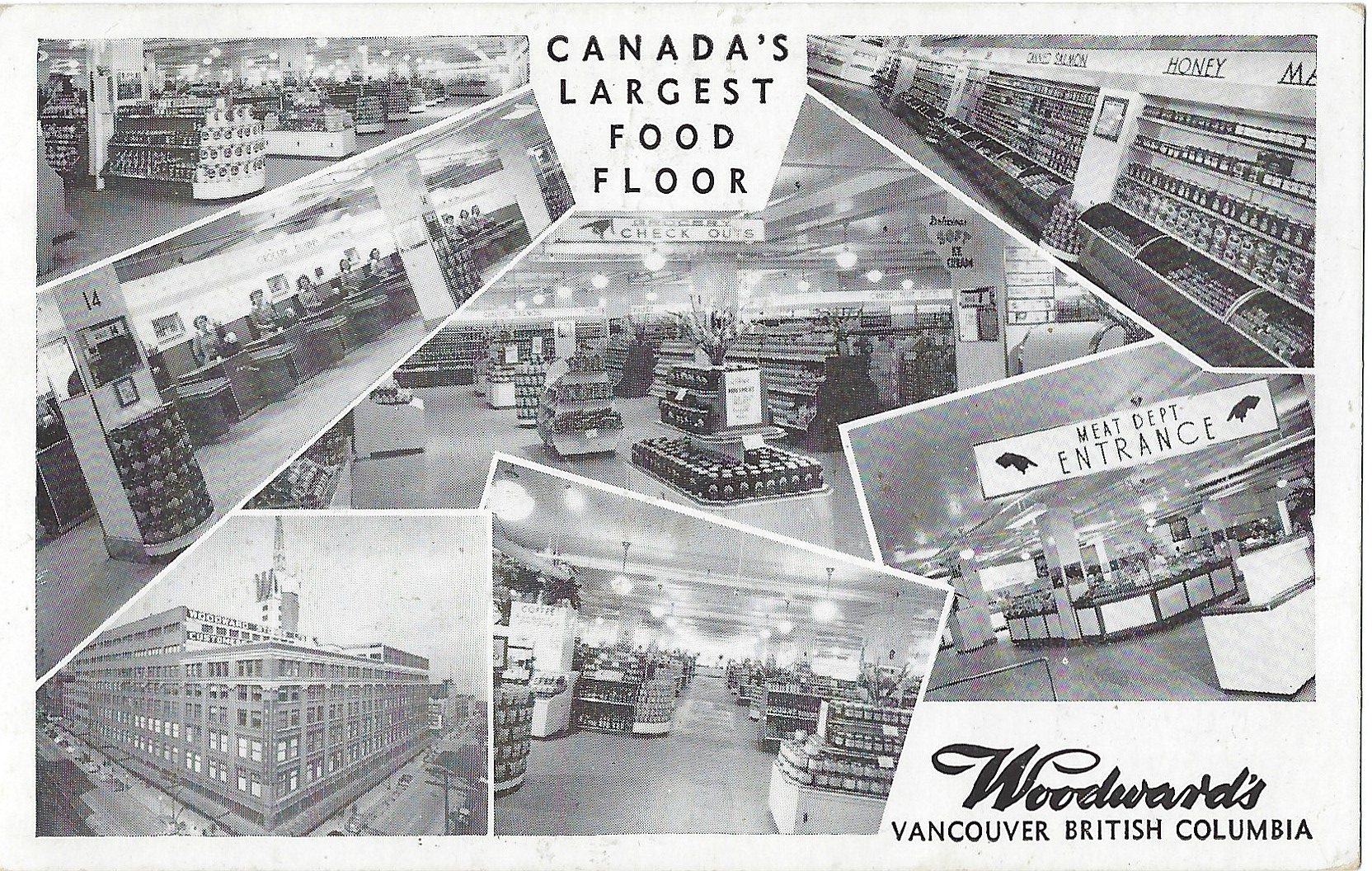

Margaret Cadwaladr has written a memoir Food Floor: My Woodward’s Days, a nostalgic walk through the area, filled with black and white and colour photos.

When I first came to Canada in the mid-1980s the Woodward’s Food Floor saved my life. It was literally the only place in Vancouver that sold jars of vegemite. And I certainly wasn’t the only one. Lots of other immigrants and travellers were able to find things from home, everything from Scandinavian rye crackers to saffron and matzo to rattlesnake meat imported from Florida.

Food Floor:

Margaret Cadwaladr kindly sent me her new memoir, Food Floor: My Woodward’s Days, a nostalgic walk through the area, filled with black and white and colour photos.

Margaret started work at the downtown Woodward’s store in 1967, but her relationship with the store, like many locals, started way before that.

“I had known Woodward’s all my life. I remember, as a child, taking the tram down Main Street with my grandfather. We would visit the hardware department then go down the wide steps to the grocery department and order cases of Carnation condensed milk, grapefruit juice and tins of food for Muggins the cat,” She writes: “The next day the blue Woodward’s truck would deliver the order.”

Test Kitchen:

There was Bea Wright’s test kitchen that dished out advice and recipes, elevator operators a small café, a book shop and $1.49 day. Employees got to take their breaks on the roof with views of the North Shore mountains and harbour.

It was a good time to work in retail. Cadwaladr says decent wages and perks such as medical benefits, paid holidays, a pension, profit-sharing and a 15% discount, kept unions out. Social events included picnics at Bowen Island and roller-skating.

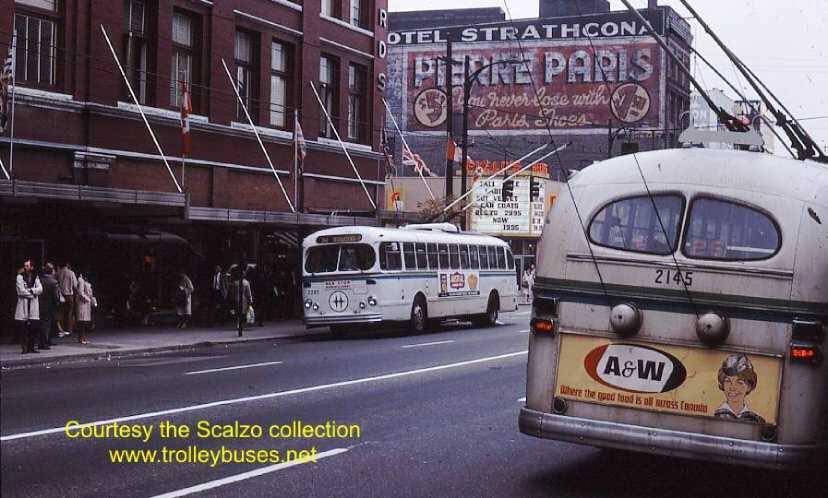

At its height, Woodward’s had 26 stores in BC and Alberta. Store #1, as it was known, operated at the corner of West Hastings and Abbott Streets for 90 years, while everything changed around it. When the store opened in 1903 for instance, the courthouse was at Victory Square and several theatres lined Hastings Street.

The chain went bankrupt in 1993 and store #1 sat empty and boarded up. The original building is now surrounded by retail stores and housing. A replica of the giant red W was installed on the new project in 2010. You can visit the original in the courtyard, near Stan Douglas’s spectacular photo mural depicting the Gastown riot of 1971.

Food Floor: My Woodward’s Days sells for $15.95 and is available through Margaret Cadwaladr’s website and Chapters/Indigo.

Related:

- The Woodward’s Christmas Windows

- $1.49 Day

- The Missing Elevator Operators of Vancouver

- A Brief History of the Woodwards Department Store

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.