The Dunsmuir Tunnel opened in July 1932. It started at Waterfront Station, passed under Thurlow, crossed to Burrard and came out by the Georgia Viaduct.

While you’re stuck for an hour on the Lions Gate Bridge or crawling through the George Massey Tunnel, it may be comforting to know that traffic problems, just like the price of real estate, have always been an issue in Vancouver.

Story from Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

The crossing:

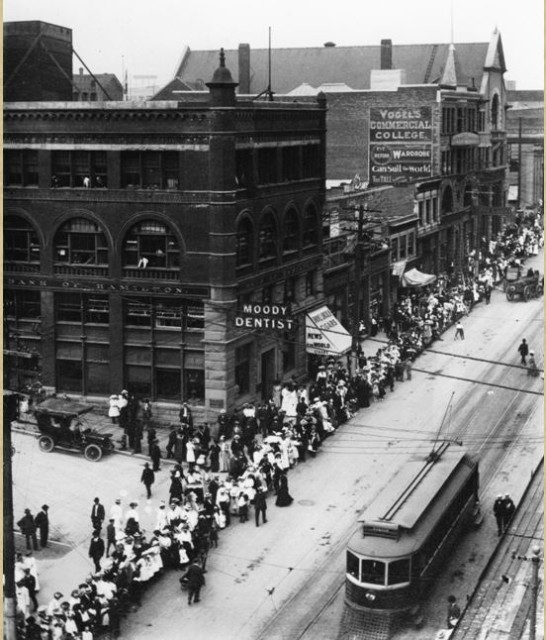

As early as 1914, there were calls for an end to the Carrall and Hastings Street crossing, where freight and passenger trains could hold up traffic for up to an hour a day getting from the CPR yards on Burrard Inlet to the yards at False Creek.

The crossing was still there in 1929 when a Vancouver Sun editorial called it an obstacle to the growth of Vancouver. “It costs Vancouver people thousands of dollars. It depreciates real estate values in the neighborhood to the extent of hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

The tunnel:

The Dunsmuir Tunnel finally opened in July 1932. The new tunnel was 1,400 metres (4,600 feet) long and lined throughout with concrete. Steam engines now followed a 190-degree arc from Waterfront Station, passing under Thurlow, crossing to Burrard and then going under Dunsmuir to Cambie where the tunnel cut under the old bus depot at Larwill Park and came out by the Georgia Viaduct.

Andy Cassidy worked for the CPR at the Drake Street roundhouse until it closed in 1981. “I travelled through that tunnel daily for years either on the passenger cars going from the station to the coach yard, or later on while taking the locomotives from the shop over to the waiting train at the station,” he told me. “I used to have to adjust the locomotive headlights regularly on the way through.”

Last train:

The last train went through the tunnel in August 1982. The tunnel then went under a $10 million renovation and was repurposed as SkyTrain’s Expo line, with the westbound track now stacked above the eastbound track. The new tunnel, with the Burrard and Granville Street stations built inside, opened in time for Expo 86.

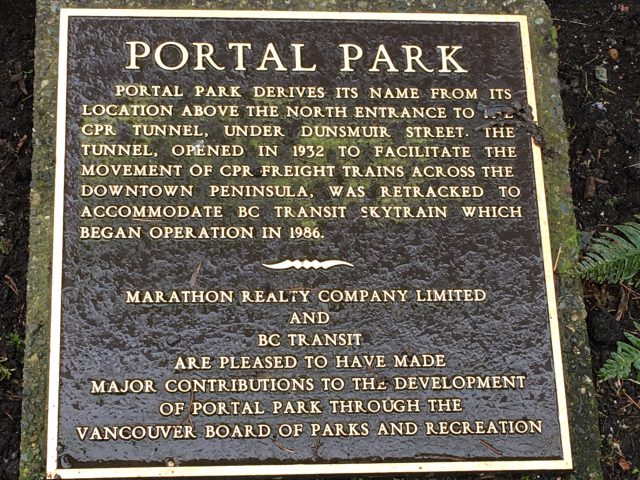

The eastern entrance to the tunnel was a concrete art deco portal set into the base of the cliff below Beatty Street. It was demolished to make way for the Cosmo, a 27-storey tower that opened in 2012. The western end of the tunnel is under Portal Park at West Hastings and Thurlow Streets—a City of Vancouver park built on a concrete roof in June 1986.

Related:

- The Dupont Street train station

- Thornton Tunnel and the fake house

- The train that ran down hastings street

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.