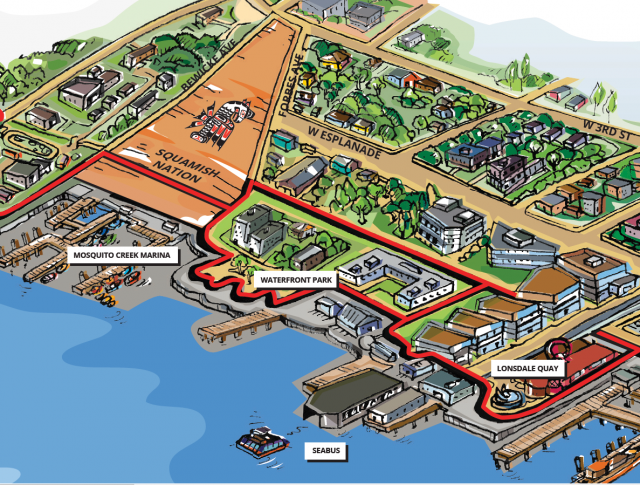

Last week we left off at the Shipyards Coffee at Lonsdale Quay. Grab your bike and we’ll ride the Spirit Trail down Cates court, loop around Waterfront Park and enter Squamish Nation land.

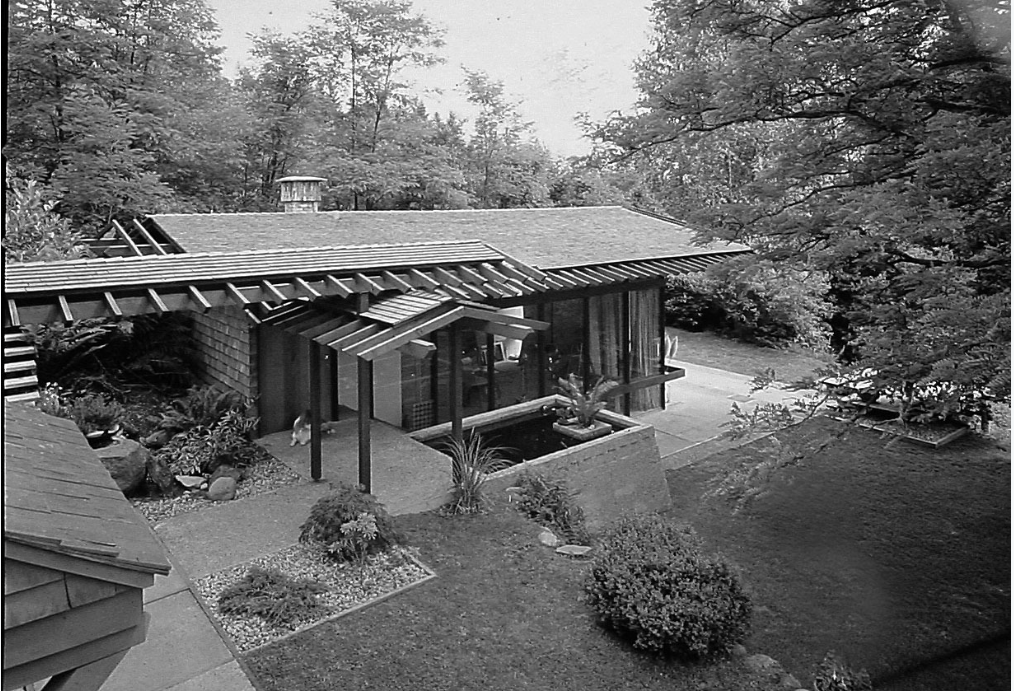

The Coast Salish aboriginal people established a permanent village called Slah-ahn (also known as Ustlawn or Eslha7an), meaning “head bay” in the 1860s. The village was located along a stretch of mudflat at the mouth of Mosquito Creek.

With the arrival of European settlers, it became known as Mission Indian Reserve No. 1—the first permanent settlement on the north shore of Burrard Inlet.

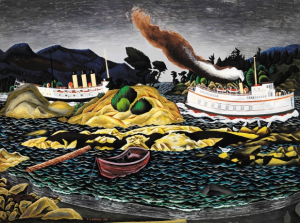

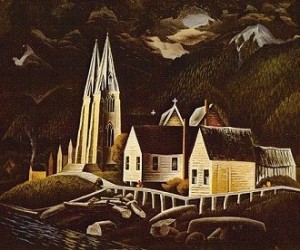

Emily Carr used to visit her friend Sophie Frank, a Squamish basket maker who lived at Mission Reserve and both she and E.J. Hughes painted the area.

In 1932, the Mission Reserve Lacrosse team won the BC Championship—they were that good. The team consisted mostly of members from the Baker, Paull, and George families, who took up the game, because as Simon Baker told a North Shore Press writer, they had nothing else to do during the Depression. “We used to practice and practice and that’s how we became famous in lacrosse. We used to pass that ball, push it in circles real fast. We were good stick handlers,” he said. The team was disbanded after the win because they couldn’t get a sponsor.

You’ll notice a vibrant community of houseboats. A diner called the High Boat Cafe, and some great art. You can also see the 1884 St. Paul’s Church with its twin spires and gothic revival style.

Over the years, the natural course of Mosquito creek has been altered by logging, landfills, and new subdivisions, destroying much of the natural habitat and salmon. Much of that is being restored and rehabilitated.

The most recent portion of the Spirit Trail was just finished this year. It runs below sea level and dips under the boat lifts at the marina. Each time we’ve been there so has a ‘haggle’ of harbour seals, sunning themselves on the wood (behind me) or swimming by the trail.

- With thanks to the NVMA which makes all this research possible.

Next Week: Harbourside to Norgate.

The North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Moodyville (part 1)

Moodyville to Lonsdale Quay (part 2)

Pemberton to Capilano River (part 6)

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.