On March 17, the District of North Vancouver unanimously approved a luxury townhome development on a chunk of land minutes from Edgemont Village. The North Shore News reported that the project included a community amenity contribution of $136,000 that could go to the district’s affordable housing fund.

How generous.

The 30,000 SF site was listed for just under $10 million and sold for $7 million. The number of townhouses were whittled down from 30 to 21.

capilano highlands

Instead of building more homes for the wealthy, why are we not building desperately needed middle-class housing?

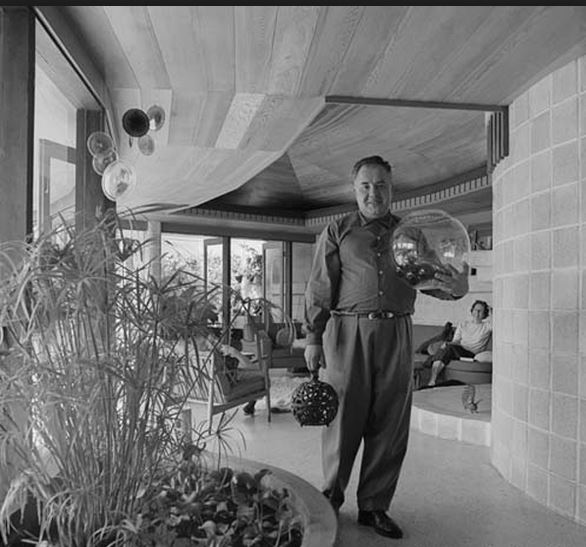

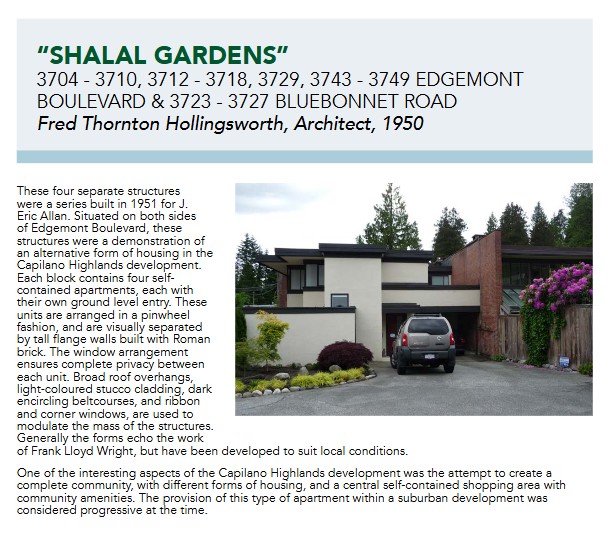

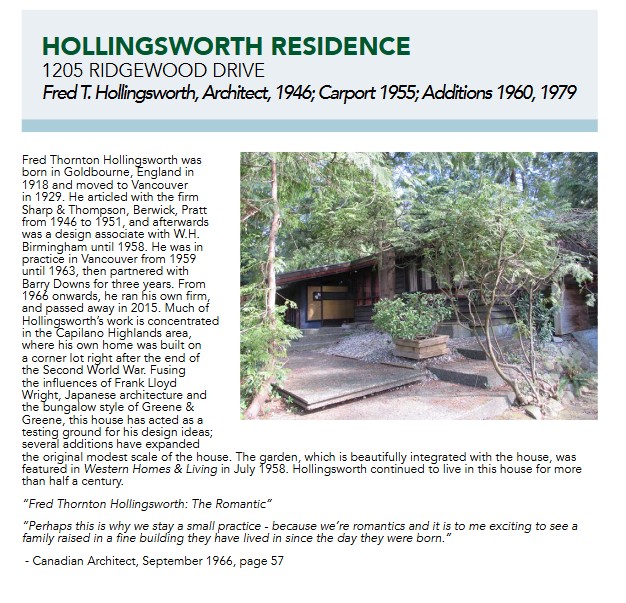

In 1949, developer Eric Allen opened up Capilano Highlands to meet the housing crisis that developed in Vancouver in the years after the Second World War. He teamed up with architect Fred Thornton Hollingsworth to bring an affordable style of West Coast modern architecture to the district where moderate income families could live and raise their families.

West Coast Modern:

These houses were mostly designed from post-and-beam construction, often with a small footprint and open plan that used glass and western red cedar to bring natural light and views of nature into the house. His houses are part art and part architecture. They are meant to blend in with the surroundings, not impose itself upon them.

Hollingsworth was inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright, in fact he met the legend in 1951 and turned down a job offer to work with him. He wanted to develop his own style.

In 1998, Hollingsworth told a Vancouver Sun reporter: “Boxes are a symbol of containment. They aren’t suitable for human occupation. You’re boxed in. We tried to open the buildings up to the landscape while providing privacy.”

Heritage Register:

People are often surprised to learn that our stock of rapidly disappearing mid-century modern houses are considered heritage and belong on the heritage registers.

The Shalal Gardens complex, Hollingsworth’s heritage buildings on Edgemont Boulevard are listed on the register. They could have been saved—the original intent was to conserve them, and then as time went by to reconstruct them. After years of dithering by the District of North Vancouver, they are now slated for demolition.

- Copies of my new book, Beneath Dark Waters: The Legacy of the Empress of Ireland Shipwreck, are available through my publisher Arsenal Pulp Press, or from any independent bookstore across Canada

Fred Hollihttps://bit.ly/40PjLimngsworth:

While his name stands for West Coast modernism and affordable homes, Hollingsworth’s architectural range was astounding. He designed the building that houses UBC’s Faculty of Law in 1971, and in 1993, he designed Nat Bosa’s West Vancouver waterfront mansion (ranked by Vancouver Magazine as the second most expensive property in BC in 2005). Yet, while he could have lived anywhere, Hollingsworth chose to spend more than half a century in the Ridgewood Drive house that he designed for his family in 1946. It’s just blocks from the Shalal Gardens.

Hollingsworth died 10 years ago this month, outliving many of his west coast modern designs. His house sold in 2018 and still stands for now.

“Think of a home in terms of a tree,” he told a Province reporter in 1949. “It should be built of natural materials, live close to the earth and provide shelter.”

This blog post has been rewritten from a longer column I wrote in the North Shore News on April 2.

Related:

- Fred Hollingsworth’s Sky Bungalow

- Our missing west coast modern heritage: what were we thinking?

- Missing Heritage

- North Shore

NO AI TRAINING: any use of this publication to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and development of machine learning language models.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.