Heritage Vancouver released their annual top 10 watch list last month (for 2021), and rather than look at endangered buildings, they have focused on space. I was interested to find Victory Square on the list—or rather not the square itself, but the buildings that surround it, some of which date back to the 1800s. The challenge, according to Heritage Vancouver, is to find the sweet spot between heritage retention and the need for low income housing.

This story is from Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

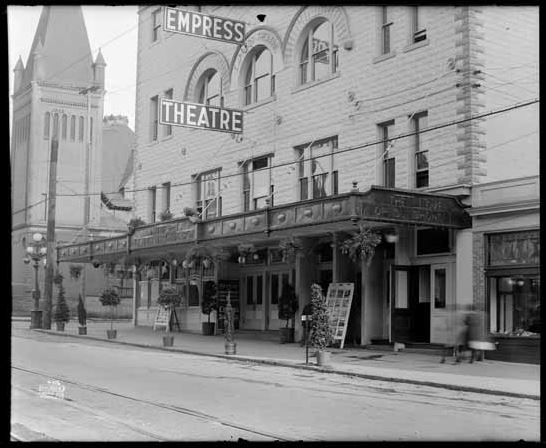

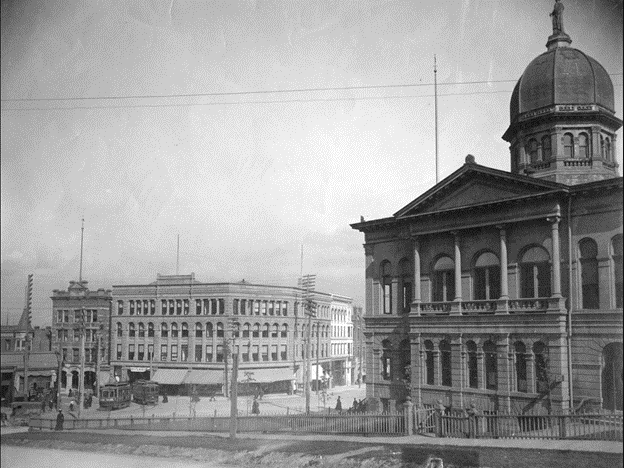

What a lot of people don’t know is that before Victory Square was Victory Square and home to the cenotaph, it was a happening part of the city known as Government Square, because it was the site of the first provincial courthouse.

The Original Vancouver Court House:

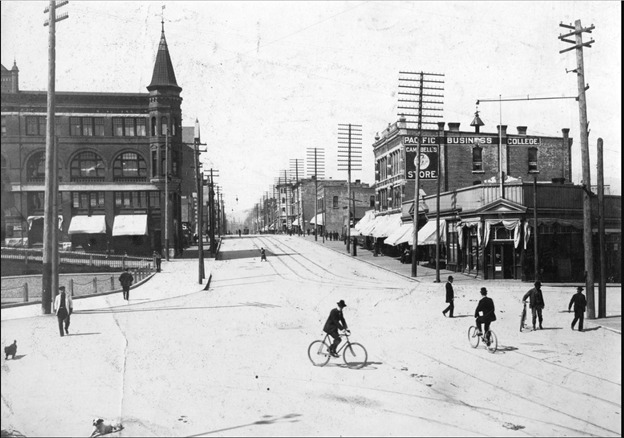

The impressive domed building was operational by 1890 and was the first major building outside of Gastown. It was quickly apparent that it was too small for our growing city, and within a few years it was given a large addition with a grand staircase and portico facing Hastings Street.

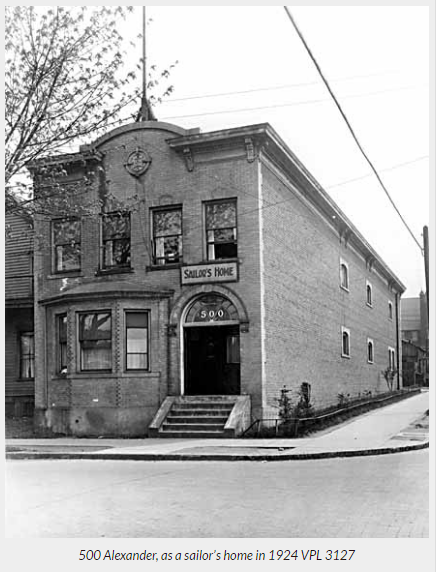

Other buildings started to spring up around the Courthouse. In 1898, architect William Blackmore (Badminton Hotel, Strathcona Elementary) designed a building for Thomas Flack who had made his fortune in the Klondike and wanted to see an impressive building bear his name.

Military and Religion:

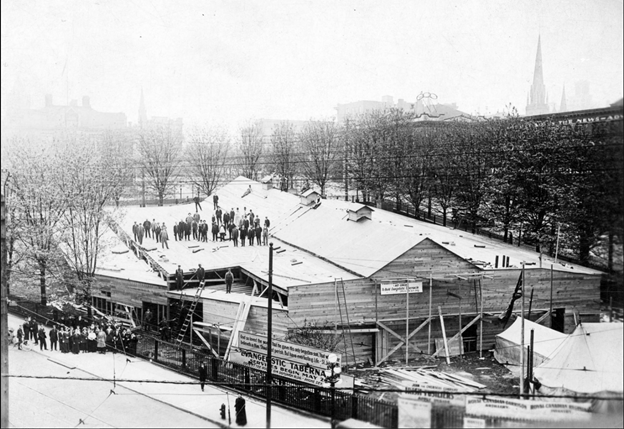

The original courthouse lasted just 20 years. It was demolished when the new law courts opened on West Georgia Street in 1912. The square, which is actually a triangle, is bounded by Hastings, Cambie, Pender and Hamilton Streets. It didn’t remain empty for long. By 1914, it was filled with a military tent, used to recruit soldiers to fight in the First World War. Then, in 1917, up went the Evangelistic Tabernacle.

The Cenotaph:

The church too was short lived. The Southams, owners of the Province Newspaper, which was housed across the street, donated funds to develop a park, which was then renamed Victory Square. By 1924, enough public money had been raised to build the cenotaph designed by G.L. Sharp. Sharp had the 30-foot cenotaph constructed from granite from Nelson Island.

The inscription facing Hastings Street reads: “Their name liveth for evermore. Facing Hamilton it says “Is it nothing to you.” And Facing Pender Street: “All ye that pass by.”

Heritage Vancouver Top 10 2021

- Pandemic spaces

- Food Hub near Joyce Station

- False Creek South

- Reconciliation and the Fairmont Building

- Mount Pleasant

- 800 Block on Granville Street

- Kingsway

- 555 West Cordova Street

- Victory Square

- Neighbourhood Businesses

© Eve Lazarus, 2022