You wouldn’t buy a house without having a building inspector check the foundation, so why wouldn’t you research your potential home’s history?

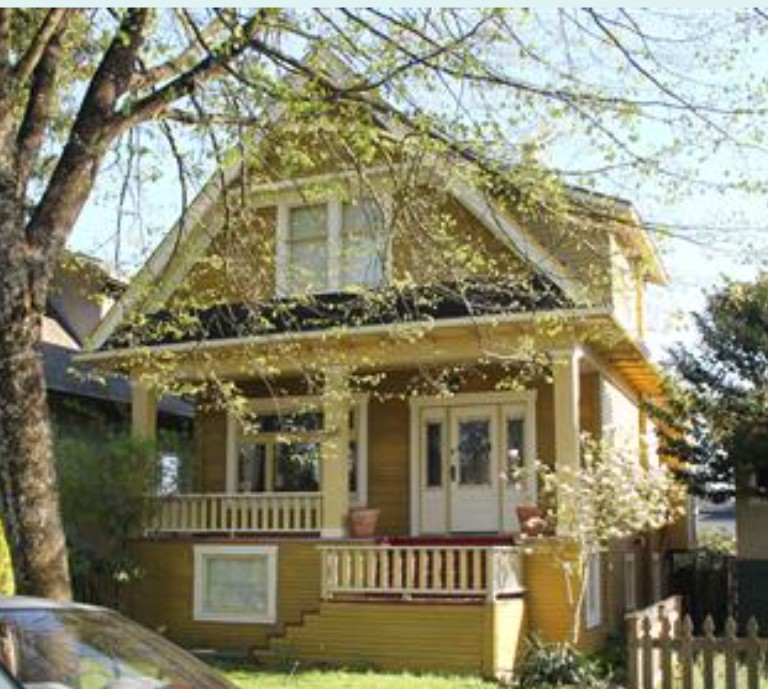

A heritage house at Fraser and East 10th went up for sale last week for $1.4 million. It wasn’t the price-tag though (low by Vancouver standards) that captured people’s attention, it was the house’s murder history.

Unsolved Murder:

The Mount Pleasant house has sat empty for 30 years—since the day in August 1991 when the 20-year-old resident was murdered. Wanda Watson had recently moved from hometown Victoria and was living in the house owned by her parents. It’s believed that Wanda surprised two robbers and was stabbed to death, and the house set on fire. Wanda’s murder remains unsolved.

Old houses have stories, but over the years they fade in people’s memories. Murders that happened before newspapers went online are just not that easy to find. House numbers change, neighbours move away, people forget, and while some homeowners will serve up a murder as dinner party fodder, most live in fear that a murder will bring down the value of their home.

In 2007, I wrote a booked called At Home With History: the secrets of Greater Vancouver’s heritage homes. The idea behind the book was that a house has a genealogy or a social history, and I included a chapter on murders that happened in houses that still stood.

HOUSE MURDERS:

The duplex where Esther Castellani was slowly poisoned to death by arsenic in 1965 and featured in Murder by Milkshake is still standing in Kerrisdale.That same year, 17-year-old Thomas Kosberg made milkshakes for his father, mother and four siblings, drugged them, and after they fell asleep, hacked the family to bits with a double-bladed axe. That story is in Vancouver Exposed and is now a podcast.

In 1971, Louise Wise had just turned 17 when she was stabbed to death in her East Vancouver home. Her story is in Cold Case Vancouver and also a podcast.

In 1975, Vancouver poet Pat Lowther, 40 was beaten to death by her husband in her house on East 46th Avenue. And, in that same year, Shaughnessy’s 68-year-old Marion Hamilton was strangled by her cousin so that she could inherit her Nanton Street house.

In the same neighbourhood, five decades earlier, 23-year-old Scottish Nanny Janet Smith was found shot in the head in the basement of her employer’s home. Her murder remains unsolved.

Selling a murder house:

Grant Stuart Gardiner is a North Vancouver realtor who specializes in selling heritage houses. He says in British Columbia, a realtor is only obliged to disclose a murder if asked.

“I’ve never had somebody ask me if there has been a murder in a house, although I have had somebody ask me if there has been a death,” he says. “If there has been one you are duty bound to disclose it, but there’s no duty to research it and try and figure it out.”

Grant doesn’t know about any murders in the houses that he’s sold, but he has had a death. He was showing a Grand Boulevard house one day when a woman came to look but refused to go up the stairs. “She said there’s some weird spirits or something spooky about this house.”

Much later a neighbour told him that a man had hung himself in the attic back in the ’50s. “If it’s not disclosed when you buy it the neighbours sure as hell tell you when you move in,” he says.

Tips on How Not to Buy a Murder House:

- Ask your realtor if there’s been a murder or suspicious death in the house

- Ask the neighbours

- Google the address. The caution here is that occasionally savvy owners have kept the house and changed the street number.

- Same idea, but this time do a free online search through your library on local papers, or if you have a subscription, through newspapers.com

- Both the Vancouver and the Victoria public libraries have murder files packed full of old newspaper clippings.

- Check the index of my true crime/history books—I may have already written about it.

I was invited on CKNW this week to talk about Would you Live in a Murder House?

Related: