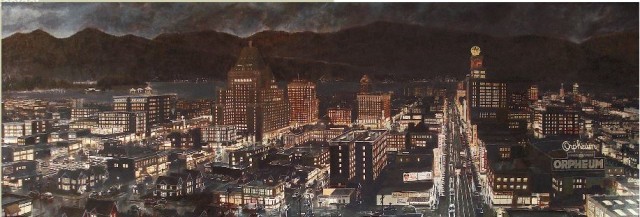

It’s hard to imagine today, but from the 1930s until the mid 1950s there were three daily newspapers—the Vancouver Sun, the Province and the Vancouver News-Herald operating in Vancouver—all independents fighting for market share in a population of less than 350,000.

The Vancouver News-Herald called itself “Western Canada’s Largest Morning Herald.” When it was founded in 1933 the Herald had a circulation of 10,000. Always the underdog, it was a feisty paper, well laid-out, and staffed with well-known newspaper people such as Pierre Berton, the paper’s city editor when he was just twenty-one, Barry Broadfoot, and Himie Koshevoy, who became managing editor at the Vancouver Sun. In those early years, reporters sat on orange crates and shared typewriters.

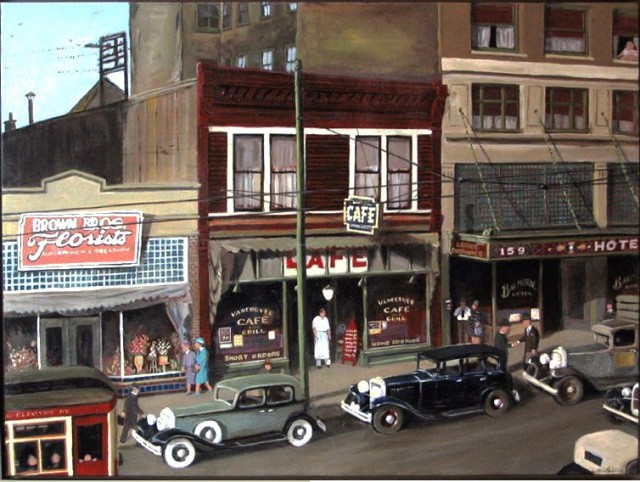

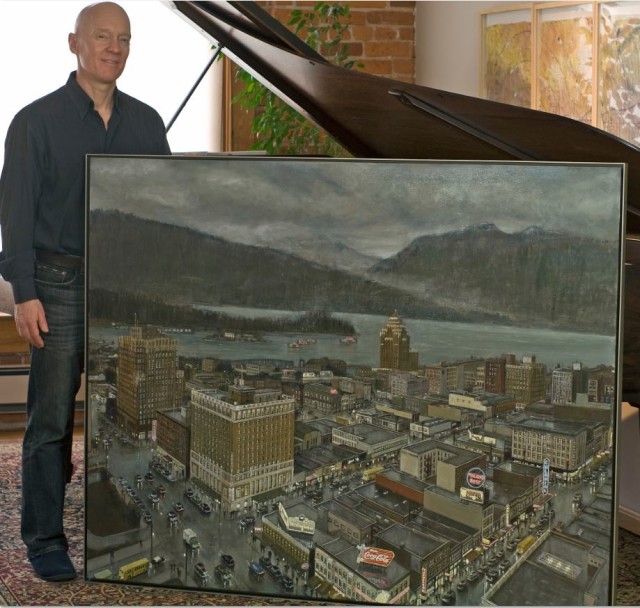

The Herald was located at 426 Homer Street for most of its existence, which is interesting because, although horribly disfigured, parts of the building still exist. It’s one of the oldest in the city. The building was designed by Samuel Maclure and Richard Sharp in 1892 for the Vancouver World—another independent owned by serial mayor L.D. Taylor. The World built what’s now the Sun Tower on Pender and Beatty Streets, and left its former digs to a series of occupants that included a real estate company, a bowling alley, printing presses and the Army and Navy Vet Association before becoming the Herald’s home in 1935.

The Herald remained on Homer for the next two decades, and in 1954 it moved to a larger building on West Georgia (where the Shangri-La Vancouver now sits). Shortly after, it went out of business.

The Homer Street building is looking a lot worse for wear these days and its current tenant is the Platinum Club, which advertises “erotic” and “safe and discreet” services from “sexy escorts.” There’s more information about the building and a great then and now picture at Changing Vancouver.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.