Beatrice Lennie created a mural for the Hotel Vancouver’s lobby in 1939. It’s been hidden behind a wall since 1967. This story is from Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History.

Beatrice Lennie:

When Beatrice Lennie graduated from the first class at the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts (now Emily Carr University of Art + Design) in 1929, it took four piano movers to shift her diploma piece. She called it “Spirit of Mining.”

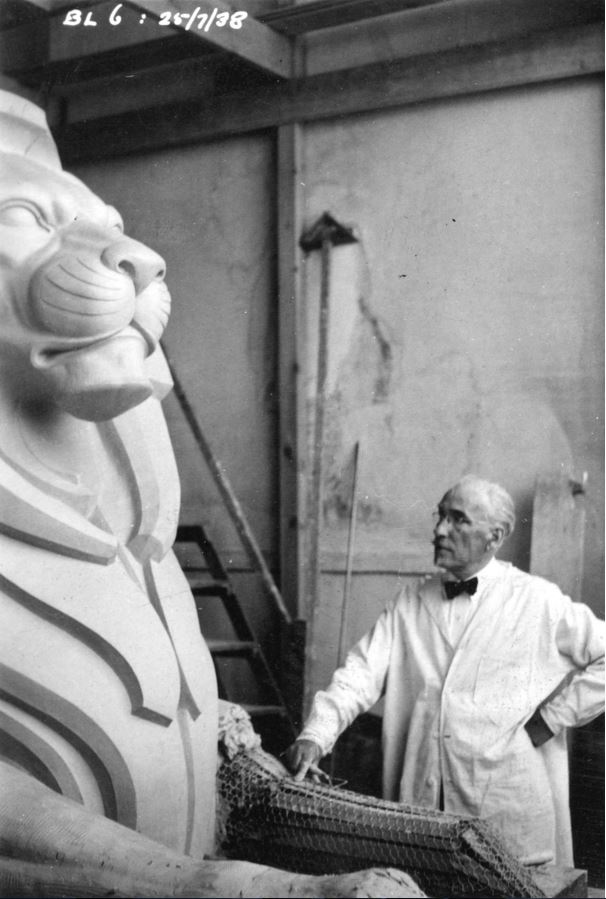

Beatrice (1905-1987) studied under Fred Varley, JWG Macdonald and Charles Marega. In 1975, she told a Province reporter that Marega had sculpted a Queen Anne ceiling for her family’s Shaughnessy home on Matthews Avenue around 1910. “It was a large decorative oval with high relief of laurel. Our ceiling was much more beautiful than Hycroft or Alvo von Alvensleben’s,” she said. “I was just a little girl when our house was built but I can vaguely remember the ceiling all coming in pieces.”

Studying sculpture:

Beatrice was the daughter of R.S. Lennie, a barrister who headed up the Lennie Commission—an enquiry into corruption in the Vancouver Police Department in 1928. Her wealthy family was horrified by her chosen career, and she received little emotional or financial support from them. “If I’d been a singer, they’d have sent me to Italy,” she told the Province. “Sculpture was not respectable or ladylike. Singing was acceptable but a woman’s place was in the home. There was terrible discrimination. Women had to be better than men. For one job I was on the scaffold at eight in the morning. I came down and just dropped in the evening. I had to prove something.”

Hotel Vancouver Commission:

In 1939, the Canadian National Railway commissioned Beatrice to create a 3.7 metre sculpture on the main floor of the new Hotel Vancouver. Called Ascension, it was finished in blue steel, brass and chromium. But when the hotel renovated the lobby in 1967, Beatrice’s sculpture and two elevators were left on the wrong side of the new wall. “I used to think sculpture would outlive you, but they bordered up one of mine,” she said eight years later. “They covered it with a wooden wall when they lowered the ceiling. It’s discouraging in one’s own lifetime.”

While you won’t be able to catch a glimpse of Ascension until the next Hotel Vancouver lobby renovation, you can see some of Beatrice’s work around Vancouver.

The Clydemont Centre, 307 West Broadway. Commissioned in 1949 when the building was the Vancouver Labour Temple.

Beatrice’s reliefs were originally at the entrance to the former Shaughnessy Hospital in 1940 when it was built as a health facility for World War 11 veterans. It’s now in the courtyard off the cafeteria at 4500 Oak Street.

Originally the College of Physicians and Surgeons of BC at 1807 West 10th Avenue, Beatrice created Asclepius in 1951. In Greek mythology, Asclepius is the god of healing and medicine.

Sources:

Province, February 28, 1975

Province, August 1, 1975

Murray Maisey, Vancouver as it Was: A Photo History Journey blog

John Steil and Aileen Stalker, Public Art in Vancouver: Angels Among Lions. Victoria: Touchwood Editions, 2009

Eve Lazarus, Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2020

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

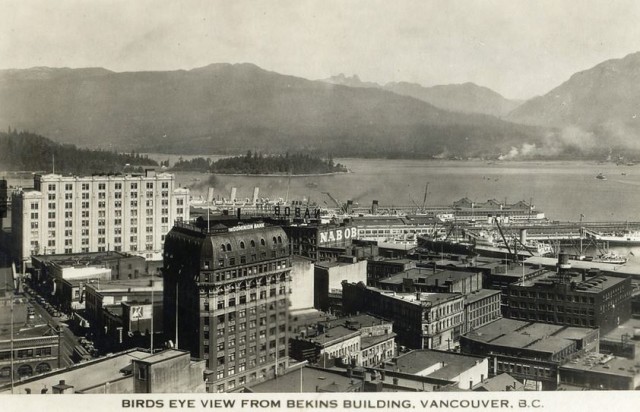

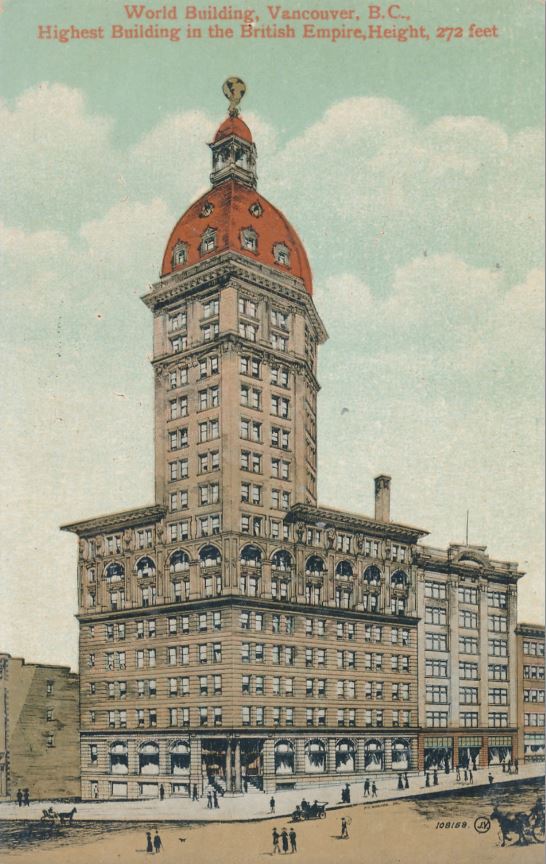

At that point Marega wasn’t very well known, but he had just shocked Vancouver’s sensibilities by carving nine topless terra cotta maidens on L.D. Taylor’s building (now the

At that point Marega wasn’t very well known, but he had just shocked Vancouver’s sensibilities by carving nine topless terra cotta maidens on L.D. Taylor’s building (now the