After you’ve spent most of December at Christmas Parties and work functions, the small talk can just dry up. Here are some conversational kickstarters to get you back on track over the holiday festivities and help you find your feet.

- The Story of the Severed Feet

I was at a Christmas party last week when the conversation turned to severed feet. You remember all those ones that turned up wearing running shoes in spots like False Creek, Richmond and Gabriola Island? It wasn’t some twisted serial killer or gang sign, when the body decomposes the feet separate (disarticulate). Normally the feet would sink, but sneakers like Nike Air have air pockets, which turns them into little life jackets. Sadly, the found feet belonged to suicides.

- The Ku Klux Klan’s Shaughnessy digs:

In 1925, the Ku Klux Klan moved into a Glen Brae, a Shaughnessy mansion on Matthews Street. While Vancouverites were a racist bunch back then, apparently living near a mob of men wearing white robes and hoods and carrying fiery crosses through the tree-lined streets, was over the top. The KKK lasted less than a year in Vancouver. The mansion is still there, it’s now Canuck’s Place Children’s Hospice.

Source: At Home With History: The Secrets of Greater Vancouver’s Heritage Houses

- Hit and Run Over:

My favourite Chuck Davis story is from October 6, 1909. Vancouver’s first mechanized ambulance was out for a trial spin, dodged a couple of streetcars and then hit and killed a wealthy American tourist crossing Granville and Pender Street. The story ran in several North American newspapers and reported that C.F. Keiss, from Austin, Texas was in Vancouver “preparing to start on an extended hunting trip.”

Source: The Chuck Davis History of Metropolitan Vancouver

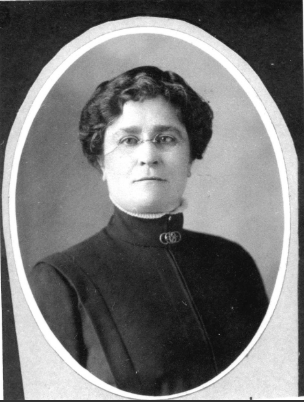

- Lurancy Harris’s Beat

If you think it’s tough being a woman in the police, RCMP or military ranks today, imagine what it was like back in 1912 when Lurancy Harris became one of the first two women police officers in Canada. She was sworn in as a fourth-class constable, given full police powers and thrown into the job with no training, no uniform and no gun. Her big break came when she got the job of escorting Lorena Mathews on the train back to Oklahoma to stand trial for murder. Mathews had bolted to Vancouver with her two children and Jim Chapman, her 25-year-old black lover who were suspected of murdering her much older husband (you just can’t make this stuff up!) Chapman was convicted, Mathews was acquitted and Lurancy got a promotion. She ended her career as an inspector with the VPD, although she was kept at the pay scale of a sergeant.

Source: Sensational Vancouver

- Shark Attack in False Creek:

On July 5, 1905 eight-year-old Harry Menzies was wading near the mouth of False Creek when he was nearly eaten by a 1,100 pound shark. “The boy ran; the shark followed,” reported the Vancouver Daily World. Ed Dusenberry saw the dorsal fin and attacked the shark with the hook of a pike pole and tried to pull it ashore. “Enraged by the pain, the shark opened its mouth and showed the most ferocious set of teeth he had ever seen, something like a man would expect in a horrible nightmare.” After it died, Dusenberry put a tent up around the shark and charged 10 cents admittance.

Source: This Day in Vancouver

- The World Belly Flop and Cannonball Diving Championship

Yup, belly flops started here in Vancouver, or more accurately, were a way to publicize the (Westin) Bayshore’s new pool in 1974. The event quickly gained momentum and spread to the old Coach House Inn in North Vancouver, drawing between 3,000 and 4,000 spectators, entrants from Fiji and Japan, as well as US President Jimmy Carter’s brother Billy as a judge. Tom Butler, the PR guy behind the stunt, told the Globe and Mail: “It’s something that is universally understood. I mean, there’s no subtlety to it. But what else can a 300-pound truck driver do and get to have NBC television declare that he’s champion of the USA?”

Source: Tom Butler, the Coach House Inn and the Belly Flop that Soared

- Loretta Lynn and the Chicken Coop

Country music singer Loretta Lynn was discovered in Vancouver. No, it wasn’t at the Cave or the Palomar or another club of those times, she was singing in a backyard chicken coop on East Kent Avenue in Fraserview. Executives from a local record company called Zero Records, and with financial backing from Art Phillips (who became mayor in 1973), heard her sing, signed her up, and Loretta’s first single “I’m a Honky Tonk Girl,” came out in 1960.

Source: Vancouver Was Awesome: A curious Pictorial History

- Van-Tan

Have you hard the story about the nudist camp at the top of Mountain Highway in North Vancouver? Turns out it’s not an urban myth, Van Tan was founded in 1939 and now has about 60 members that get to hang out sans clothes on several acres of cleared forest. When you get to the car park, it’s behind a locked gate, and another two clicks up a curvy, unpaved road. Sure you can hike it, but why not wait and check it out at one of their open houses this summer?

Source: Van Tan Nudist Camp

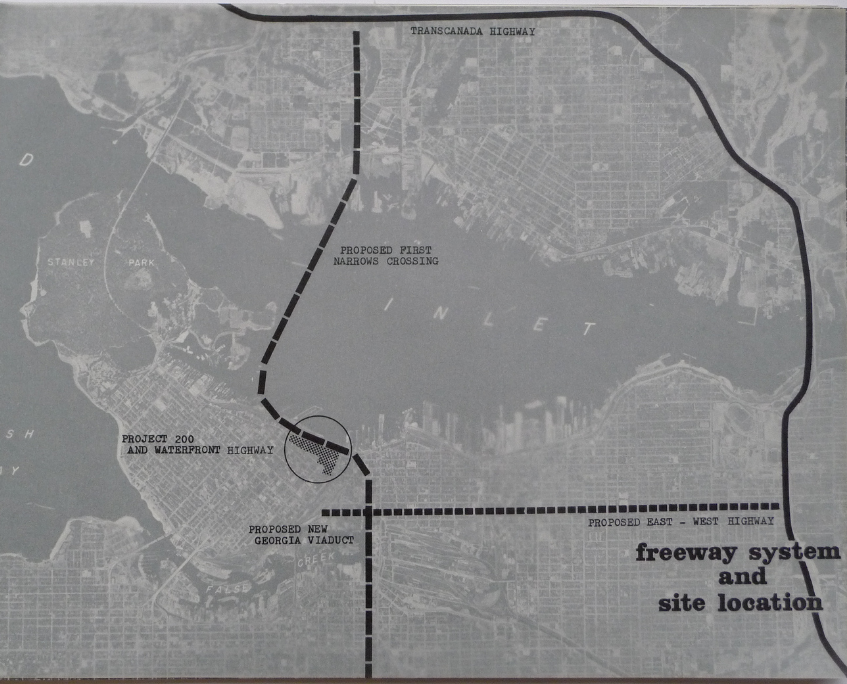

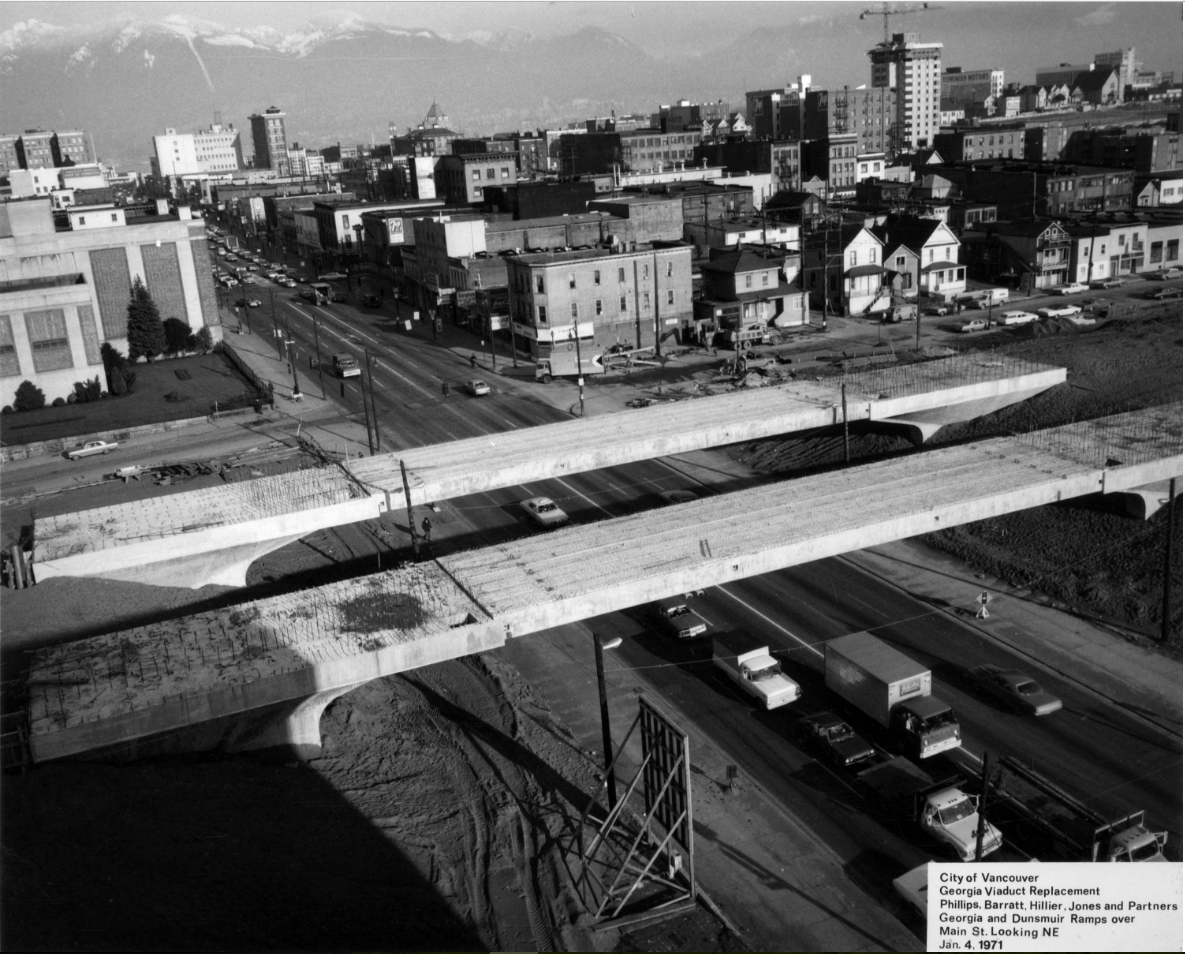

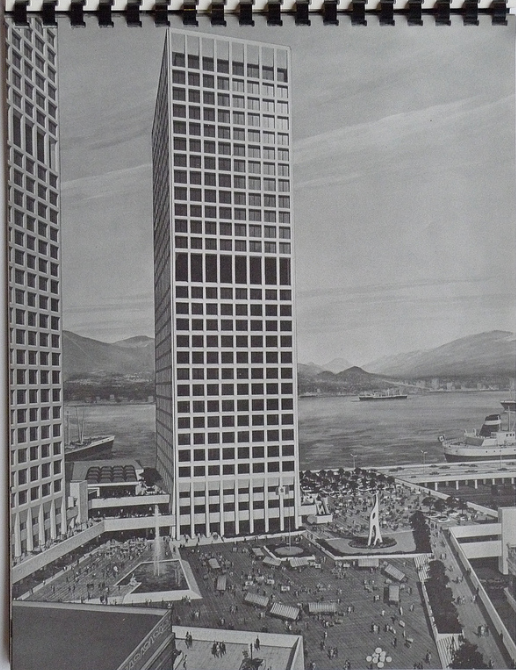

- Project 200

Gordon Price called it “the most important thing that never happened” to Vancouver, and certainly if Project 200 and the rest of the freeway plans had gone ahead, Vancouver would be unrecognizable today. The plan was to construct a freeway system that would connect Vancouver to the Trans-Canada Highway and to Highway 99. The freeway would run between Union and Prior Streets, and wipe out Strathcona, most of Chinatown, much of the West End, plop an ocean parkway along English Bay, and turn Vancouver into a mini Los Angeles. To get a sense of the magnitude of Project 200, check out the plaza and the tower at the foot of Granville Street. Then imagine a forest of office and residential towers, plazas, a major hotel, and parking for 7,000 cars that would take out Waterfront Station, most of the Sinclair Centre and the heritage buildings in Gastown.

Source: aborted plans

- The Murder Factory

If you are driving up East Cordova Street these holidays, take a look at #629. It’s now a duplex, but back in 1931 it was a “private hospital” run by a Japanese man named Shinkichi Sakurada. Sick people would go in, they’d take out an insurance policy naming Sakurada as their beneficiary, and then they would die. According to the Globe and Mail, the “murder factory” was run by an “organized assassination ring” and was responsible for as many as 20 deaths.

Source: Blood, Sweat, and Fear: The Story of Inspector Vance, Vancouver’s First Forensic Investigator

For more ideas: Eve Lazarus Books

https://evelazarus.com/books/© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.