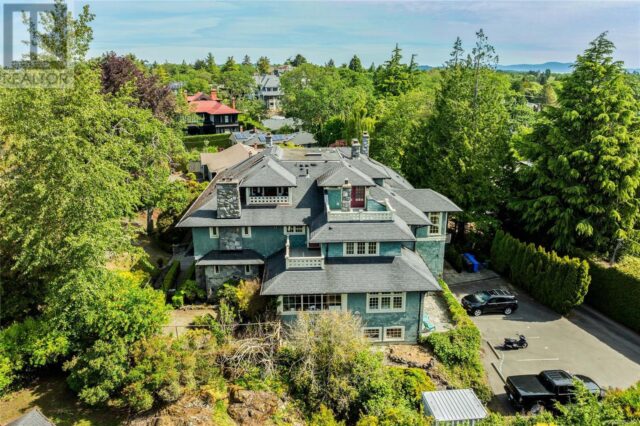

Emily Carr’s 100-year-old Oak Bay cabin could be yours for $5.5 million dollars! The good news is that it comes with a 10-bedroom heritage house designed by Samuel Maclure.

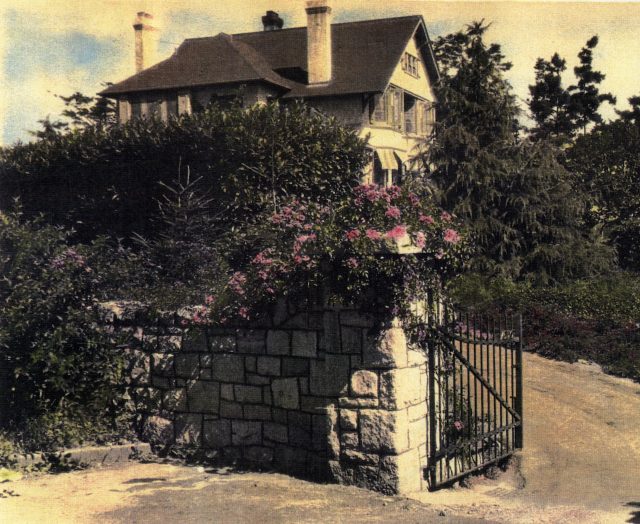

In 1913, Emily Carr paid $900 for a plot of land on Victoria Avenue in Oak Bay. According to a story,* she built a 12 by 20 foot cabin the following year, “nail by nail” at a cost of $150 with the help of “one old carpenter.”

Assessment records show that the builder was Thomas Cattarall, the same “old carpenter” who built Craigdarroch for the Dunsmuir family and later worked with architect Samuel Maclure on Hatley Castle. By 1914, he was 70, retired, and living not far away on Beach Drive.

Story from: Sensational Victoria

Emily wrote extensively about James Bay and her family home in The Book of Small, about her time as a landlady in The House of All Sorts, and about selling that house, her family home, and her later houses in Hundreds and Thousands. Yet with all these books, including her biography, there is not one mention of the Oak Bay cabin.

Probably the cabin was a much-needed refuge from her hated landlady duties, a place she could escape to in summer.

Sold in 1919:

In 1919, both her sisters Clara and Edith died, and Emily sold her cottage to Ellen Hodgson Phipps, the wife of a local farmer. The little cottage went through a series of owners and renters—mostly single women—as well as a number of alterations. In 1995, new owners wanted to build a house on the property but didn’t want to destroy the cottage. They tried to give the cabin to the provincial government which runs Carr House, but officials said no thanks.

At this point Terry Tallentire stepped in. She paid the city $1.00 and then spent another $4,000 to move it to her house at 825 Foul Bay Road. An artist herself, Terry used Emily’s cabin for her studio. She moved years ago, but the cabin remained.

New owners were renovating the house into suites when I was researching this story in 2011 and I was able to get in and have a look around. According to the current real estate listing, it has a 3,600 sq.ft. owner’s suite, five private suites, and one “historic detached cottage.”

Emily loathed being a landlady, but somehow, I think she would have liked this house.

*Mention of the “story” was in Emily Carr: The Untold Story, by Edythe Hembroff-Schleicher (1978)

Related:

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.