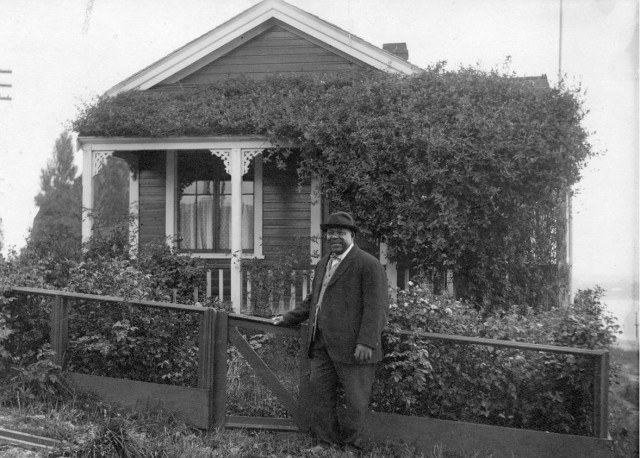

About six years ago, I was doing some research for my book Sensational Vancouver and took a tour of Strathcona with James Johnstone. I was excited to meet Paul Yee, a historian who now lives in Toronto, and has written several brilliant books which include Salt Water City, Tales from Gold Mountain, and most recently, A Superior Man (see Paul’s website for a full list).

Paul told me that he lived in three different houses in Strathcona between 1960 and 1974.

“I was an orphan,” he said. “When whole blocks of houses around me were demolished, I felt like I was being shoved onto a stage for the world to see all the shame that came from living in a slum. Even as a child, I knew Vancouver had better neighbourhoods. I was embarrassed to tell people my address, show others my library card.”

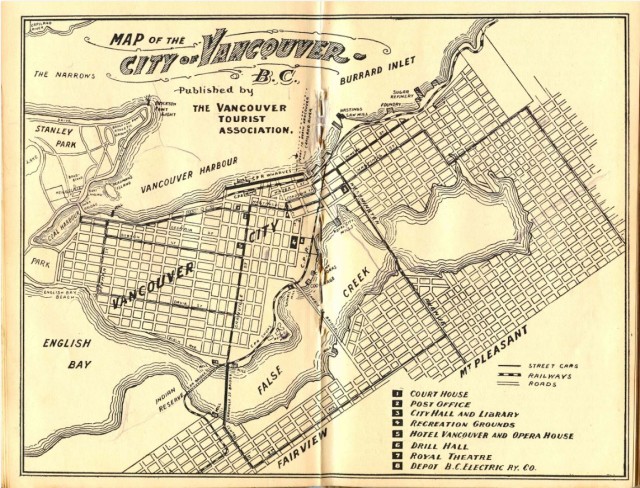

Paul’s first address was 350 ½ East Pender Street. The house is long gone, and the ½ refers to a smaller house that stood at the rear of the main residence, he says. The family left in 1968 to live above the Yee’s family store at 263 East Pender, and in 1971 they moved to 540 Heatley Street. Later, the Yee’s moved east into the Grandview Woodlands Neighbourhood.

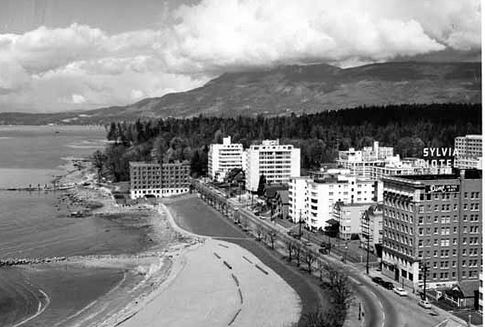

Paul, was amazed at how much Strathcona had changed “When I walk through Strathcona now, what really hits me is how green and lush it is. The place is now respectable, unlike when I lived there,” he said.

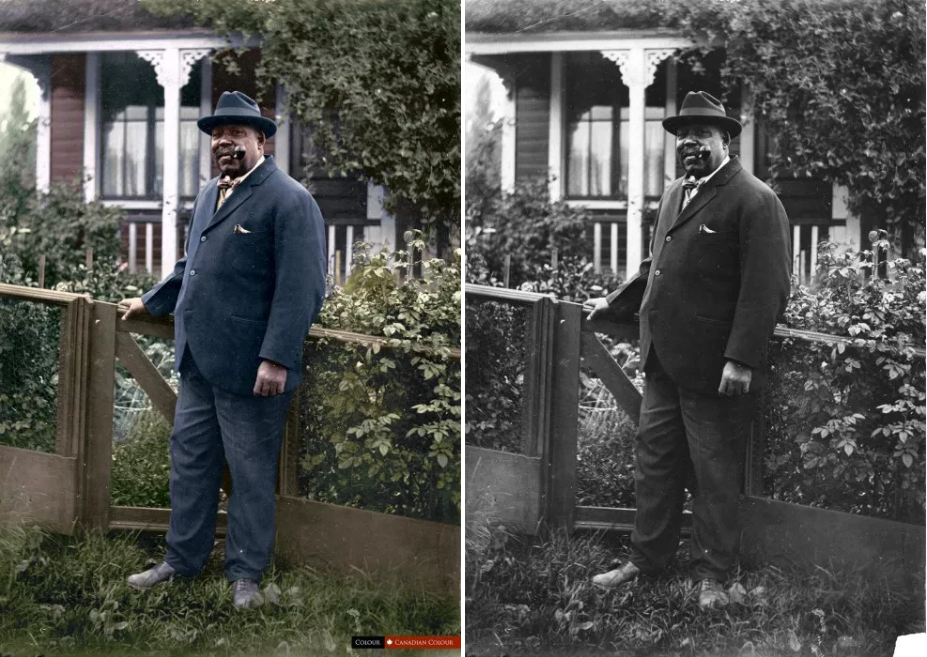

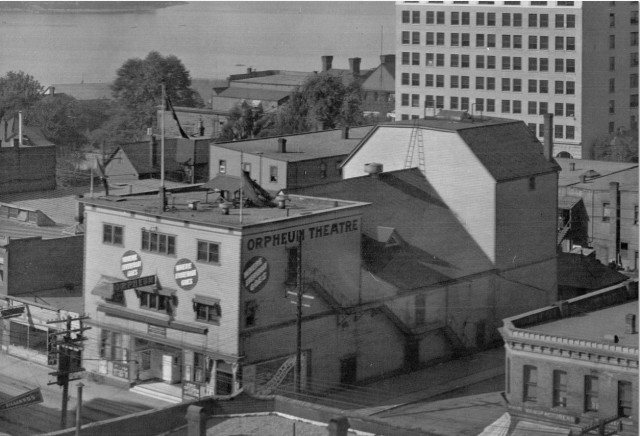

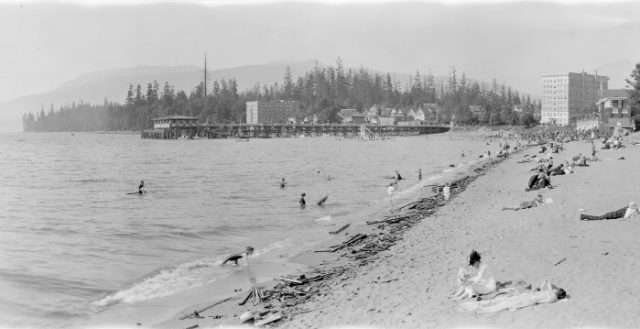

This week, Vancouver Archives announced that thanks to funding from the Friends of the Vancouver City Archives, they have now digitized 3,700 photos that the Yee family donated in 2014. Many are Paul’s own photos, and there are also oral interviews online from the ‘70s and ‘80s with Chinese Canadian seniors and community members. You can read more about it on their great blog AuthentiCity.

Many of the historical photos that you see in our books and on the many Facebook pages that are about “old” Vancouver, including my own Every Place has a Story, come from Vancouver Archives, and it’s all free of charge. It’s an incredible resource, and if you become a member of the Friends of the Vancouver Archives, your money goes to digitizing more of these records.

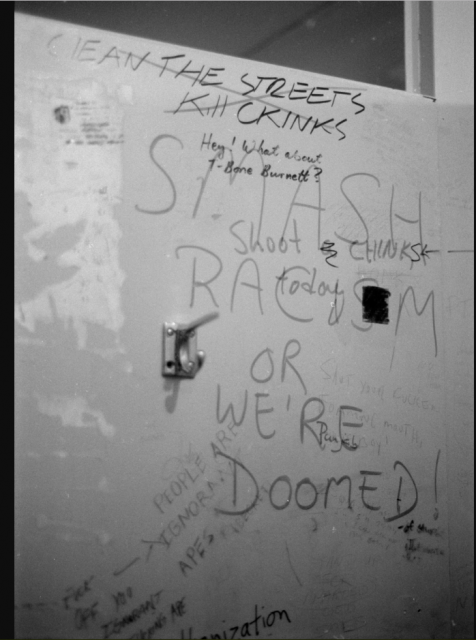

Personally, I’m looking forward to the AGM on March 31 with guest speaker Ron Dutton. Ron started the BC Gay and Lesbian Archives in 1976, and he recently donated over 750,000 posters, sound recordings, photographs, magazines and clippings to the Archives.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.