The Vancouver Aquarium opened on June 15, 1976. Before that there were two other locations at English Bay and Hastings Park.

Hastings Park:

The first Vancouver Aquarium opened in Hastings Park around 1913. I stumbled over this while on Murray Maisey’s excellent blog Vancouver as it Was. According to a Vancouver Daily World article from 1910 that Murray found, it would not be: “a dinky little pool with some tame goldfish swimming leisurely around, but a real concrete aquarium with a glass front and all the fixings big enough to keep sharks.” By 1941, the aquarium was gone, its former digs renamed the museum building, and it became the first home of the Edward and Mary Lipsett collection. The collection was part of a display at the PNE that year and has been with the Museum of Vancouver at Vanier Park since 1971.

English Bay:

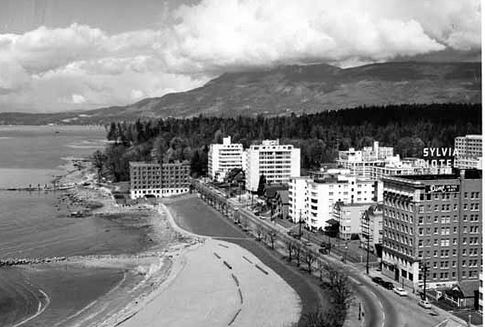

The second aquarium opened in the English Bay Bathhouse in 1939. This was totally confusing to me until I found the Vancouver Archives photo (above) that showed the two early bathhouses together—the concrete one left of frame, housed the Aquarium just east of Gilford Street and was demolished in 1964. Our current art deco one is up the beach right of frame.

This lovely wooden bathhouse opened in 1906 and was demolished in 1931 when it was replaced by our current one. CVA 447-18, 1919

This lovely wooden bathhouse opened in 1906 and was demolished in 1931 when it was replaced by our current one. CVA 447-18, 1919

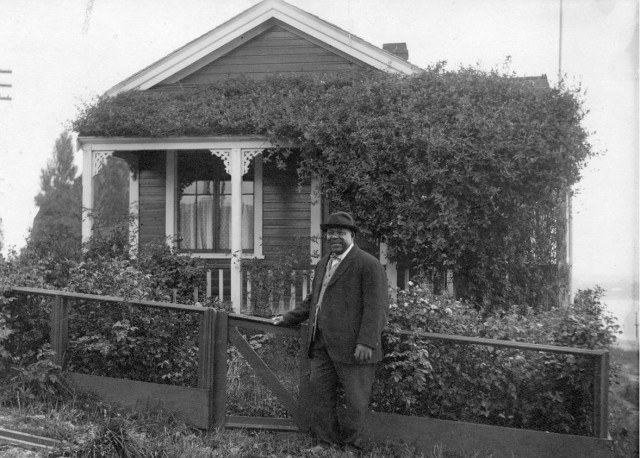

A guy called Ivar Haglund, who already operated an aquarium in Seattle, applied and received permission to open a Vancouver version in 6,000 square feet of bathhouse, down the stone stairs and just below the sidewalk. The deal was it would be a 10-year lease and the Parks Board would get 7 percent of the gross takings in the first year and 10 percent after that. Must have seemed like money from heaven in 1939.

Oscar and Oliver:

Ivar moved in “over 100 varieties of sea life” including minnows, smelts, skate, clams and crabs.” The star attraction were some seals and a couple of octopus named Oscar and Oliver (that were quietly replaced with other lookalikes after they repeatedly failed to survive in captivity). In 1966, a former aquarium cashier told a Vancouver Sun reporter that “the problem wasn’t obtaining the aquatic life, but simply keeping it alive.”

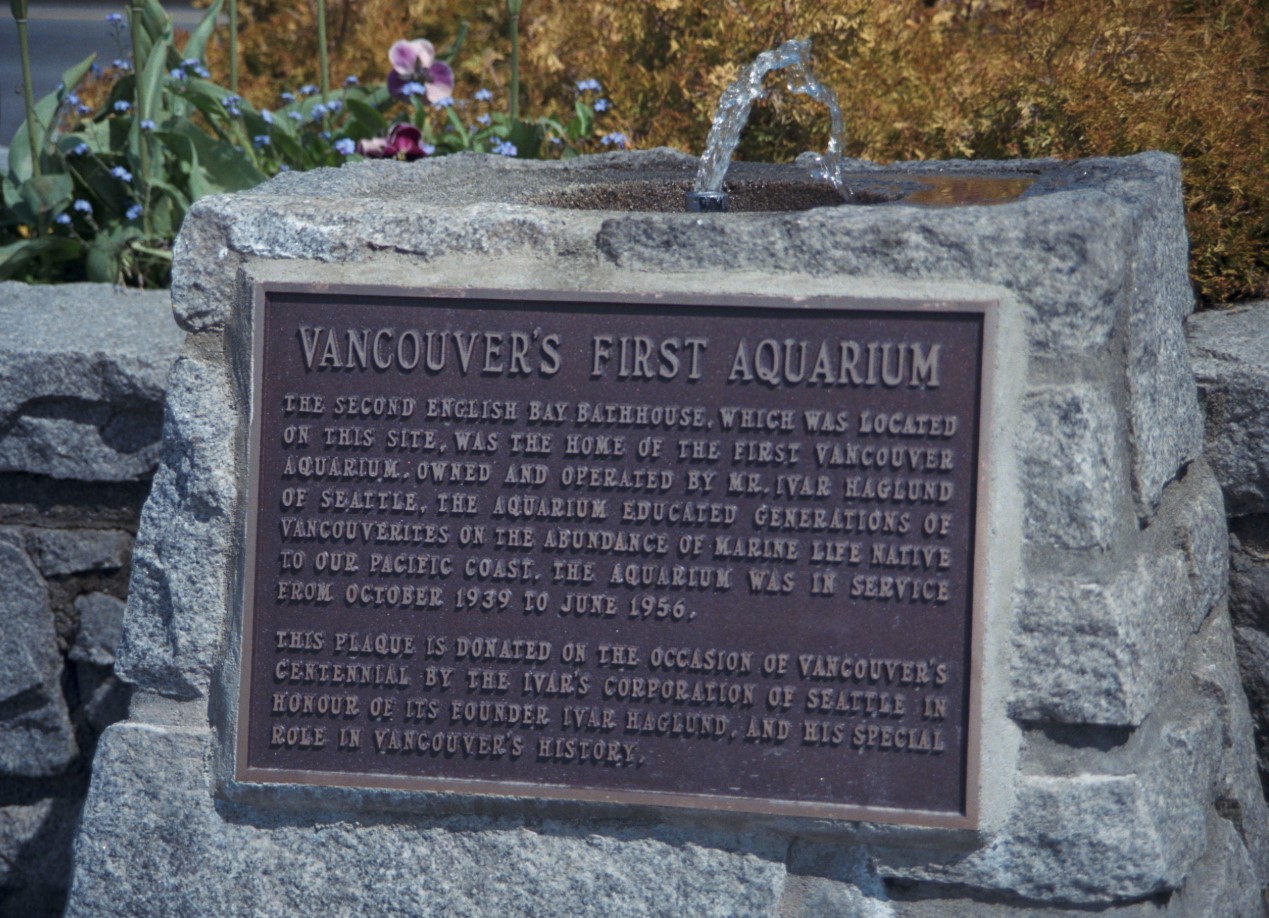

Ivar’s Aquarium closed in 1956, when our current one opened. I found this Vancouver Archives photo of the plaque taken in 1986 and situated just across from Morton Park. Have no idea if it’s still there.

- With special thanks to Murray Maisey and Neil Whaley

Related:

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.