Henry Switzer’s shocking pink house sat at Mathers and Taylor Way in West Vancouver. It was designed one Sunday and received attention from all over the world.

Local Landmark:

A few years ago, I wrote a story about a West Vancouver house that became a local landmark. Readers told me that they fondly remembered the pink house on the hill as the “airplane house,” the “Jetsons House,” the “windmill house,” and the “helicopter house,” because it appeared to have wings. Legend has it that Henry Switzer designed the house in an afternoon.

Unfortunately, Henry’s home only lasted for 11 years. In 1971, it was expropriated along with 50 or so other houses between Taylor Way and Horseshoe Bay to make way for the widening of the Upper Levels Highway.

Switzer House:

Henry’s great nephew Daryl Parsons recently sent me a photo of the 1,600 sq.ft house. He put me in touch with his uncle Garth Switzer, who helped Henry build his house in 1960.

Garth says the house was designed for the California hills. “One arm was the kitchen eating area, one arm was the living area and the other two were bedrooms and bathrooms,” he says. “I’m told it took about two months to knock it down because there was so much rebar and all sorts of high-density concrete.”

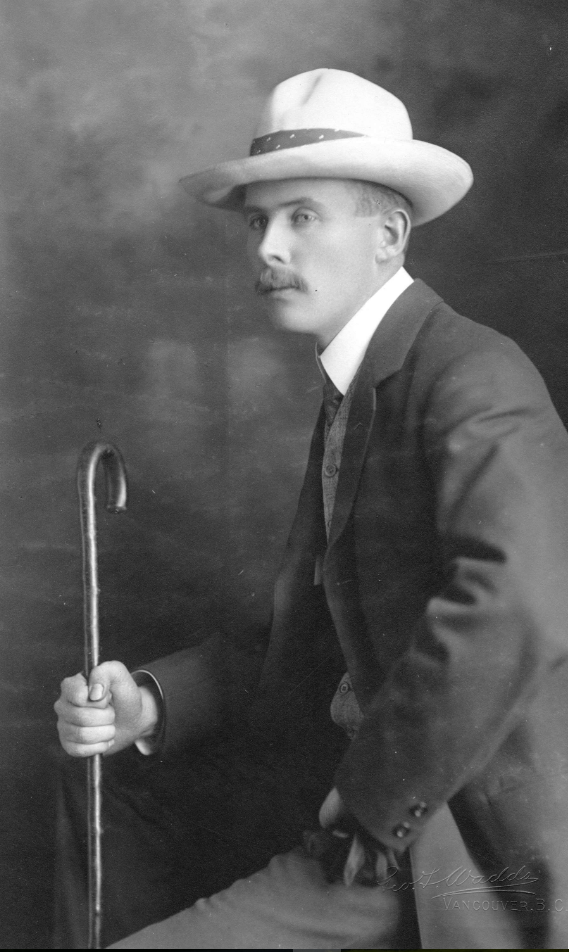

Curly Switzer:

But Henry was much more than his house. He was born in Bells Corner, Ottawa in 1904, and was the youngest of 15 children. During the 1940s and ‘50s he was the Superintendent at Marwell Construction, one of the largest construction companies in Western Canada. Henry worked on the city hall and the high school in Rossland, on the Fernie General Hospital, and the courthouse in Chilliwack. Later, he formed his own company. “I have very fond memories of his house, his gold teeth, his pink Cadillacs and his band—Curly Switzer and the Red Mountain Boys,” says Daryl. “He was a very charismatic, charming and entertaining guy.”

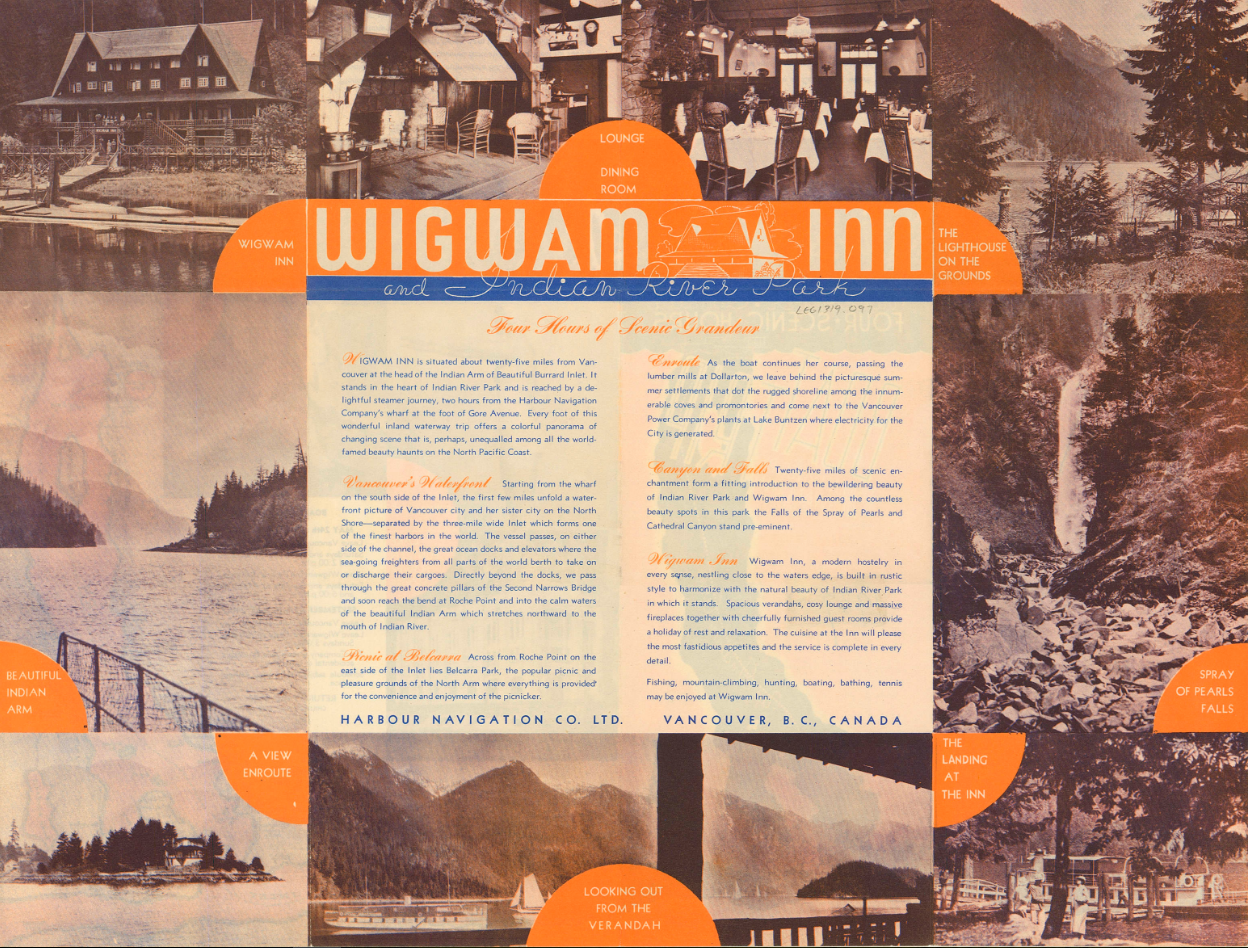

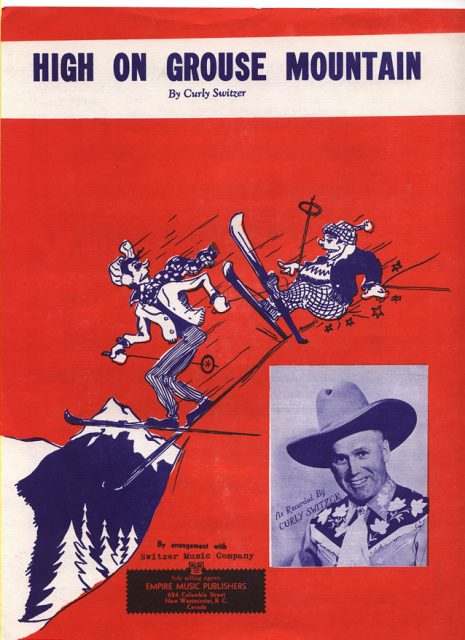

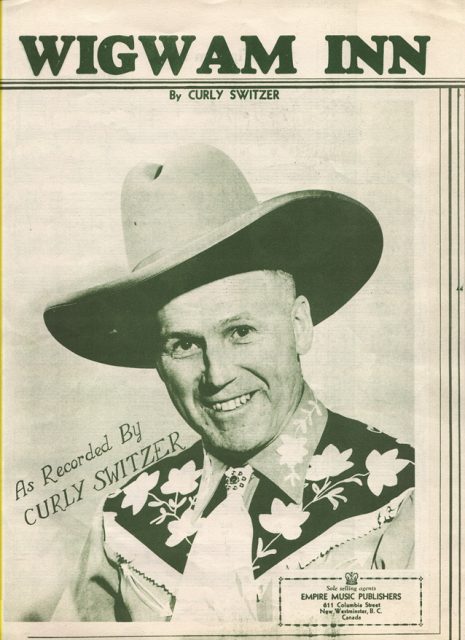

Henry or Curly as he was known, was a musician and a composer. His songs include “High on Grouse Mountain,” “Wigwam Inn,” and “The Malibu.” Henry’s wife Eleanor was a noted pianist, and Garth tells me that Peter Cowan, co-owner of Harbour Navigation and the Wigwam Inn, played the bass fiddle in the band in the early 1950s. “We had our Christmas dinner at the Wigwam Inn. Curly organized it and the band played. He was dressed up in his black cowboy shirt and pants, stetson hat and a couple of 45s on a holster,” says Garth. “He played a steel slide guitar, and he had a pretty decent voice.”

Shortly after this, the Wigman Inn became known for more nefarious activities. But if anyone has one of Curly Switzer’s albums I would very much like to hear it!

Henry died in 1976.

Related Stories:

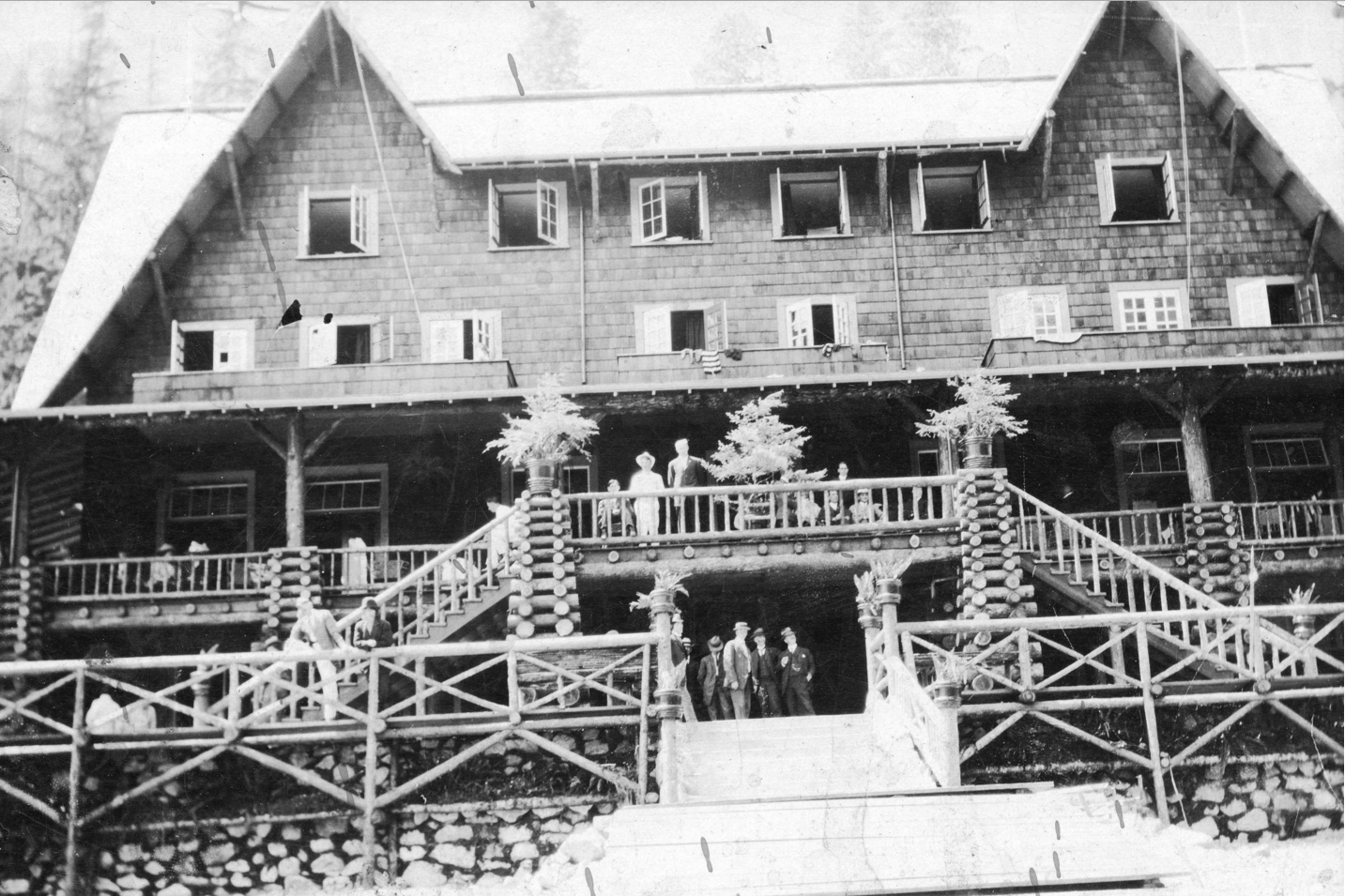

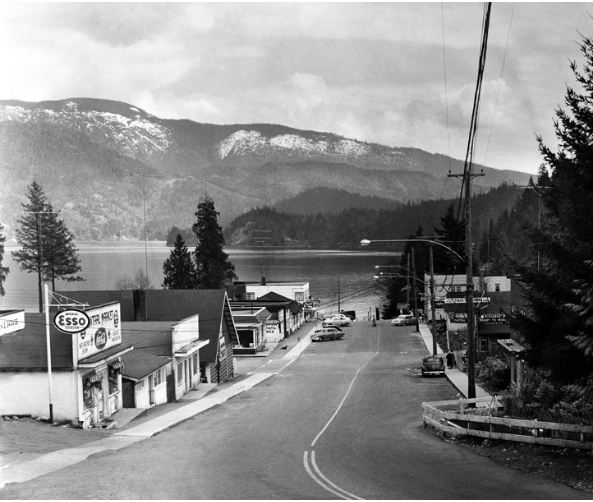

- The Wigwam Inn on Indian Arm

- Switzer House (1960-1971)

- Department of Highways film 1966 – Horseshoe Bay to Burnaby

© Eve Lazarus, 2022