Love this photo taken in 1921 from Howe Street looking down West Hastings. The big building closest to the photographer is the Metropolitan at 837 West Hastings. It was built in 1912 to house the Metropolitan Club which then became the Terminal City Club and the building lasted until 1998. It was replaced with a 30-storey building called the Terminal City Tower. We also lost the beautiful lamp standards as well as the building next to it—which was the original Vancouver Club, built in 1893 and with members who lived close by back then, and included people such as Henry Ceperley, B.T. Rogers, Alfred St. George Hamersley, Gerry McGeer, Wendell Farris, H.R. MacMillan, and the building’s architect Charles Wickenden.

The second Vancouver Club, which is still there, was built in 1913.

It seems amazing now, but in 1914 there were seven men’s clubs all in fairly close proximity. The Vancouver Club was made up of the city’s elite, while the Terminal City Club attracted a scrappier crowd that had to earn their own money. Others were the University Club at Cordova and Seymour, the Commercial Club in the Vancouver Block, the Public Schools Club at 700 Cambie Street, the United Services Club at 1255 Pender, and the Western Club at Dunsmuir and Hornby.

When the Vancouver Club took its members to the new building at 915 West Hastings, the 72nd Seaforth Highlanders Regiment moved in and stayed until 1918 after which the building became the home of the Great War Veterans Association, and in 1925, the Quadra Club.

Jason Vanderhill sent me a couple of links to photos of the old Vancouver Club, which he had zoomed in on and found some interesting signage. “On the left you can see the new Vancouver Club; on the right, the telltale notice of development!” notes Jason. “I can barely read the signs, but I can just make out on the left, the sign starts out: “Be proud to live in Vancouver, some very small print. Pemberton & Son. On the right, the sign says: ‘This property to be developed on expiry of existing lease. Will sell for $375,000 For space see Pemberton & Son’.”

It seems that even 85 years ago we were flogging houses with the demolition permit attached.

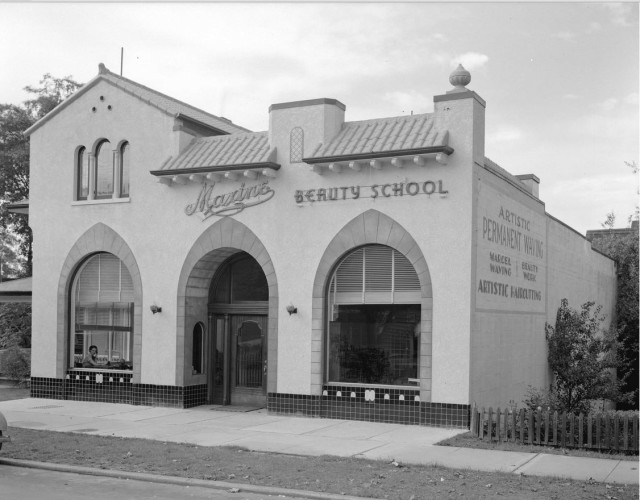

And, as the photos show, the old Vancouver Club came down in 1930, and its tenant the Quadra Club moved to 1021 West Hastings, near the spanking new Marine Building.

For more posts see: Our Missing Heritage

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.