1967:

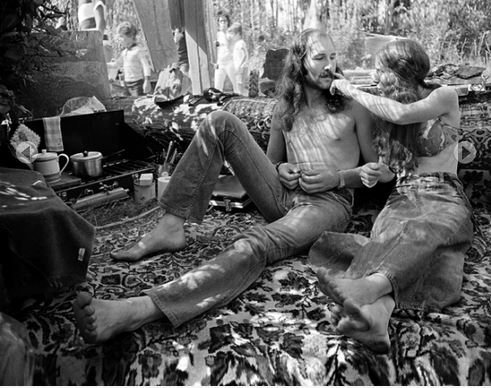

It’s been 57 years since the first Stanley Park Be-In. A local take on the be-in that had taken place in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park two months before and set the tone for the Summer of Love.

Vancouver’s event was much smaller, but about a thousand hippies, and three times as many onlookers, turned up at Ceperley Park near Second Beach in March 1967, wearing colourful beaded vests with jeans and tattered evening gowns, even monk and clown costumes. They danced to bands like Country Joe and the Fish, dropped LSD, and carried signs that read, Make Love, Not War, and Burn Pot, Not People.

This event officially marked the beginnings of Vancouver’s counterculture and set the stage for the launch of the movement’s newspaper, the Georgia Straight, the first issue of which hit the streets on May 5 1967, with a cover price of 10 cents.

1972:

The sixth annual Easter Be-In was held on April 2, 1972. Less than three weeks later, the Park Board would unleash the bulldozers and demolish the hippy huts in All Seasons Park. Thanks to their tenacity and ability to live without running water (the hippies not the Parks Board), instead of a huge hotel and condo development, we have Devonian Harbour Park.

1973:

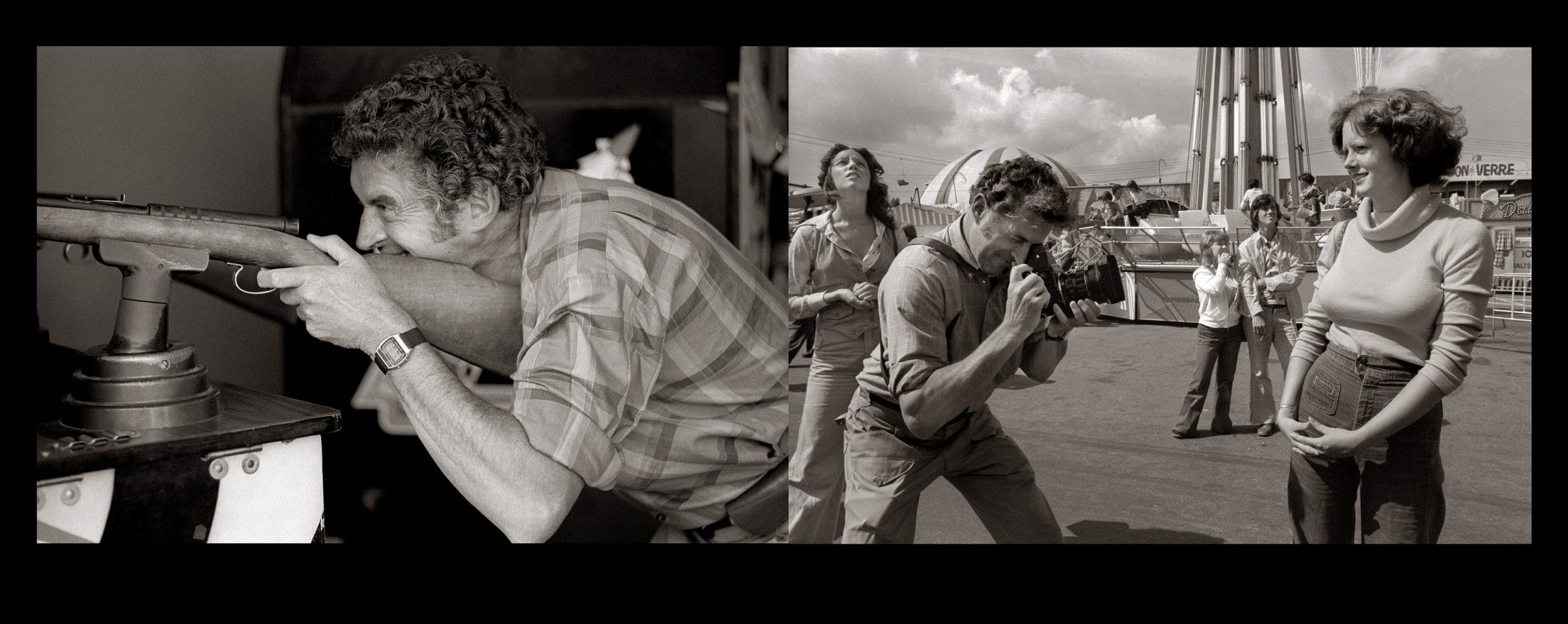

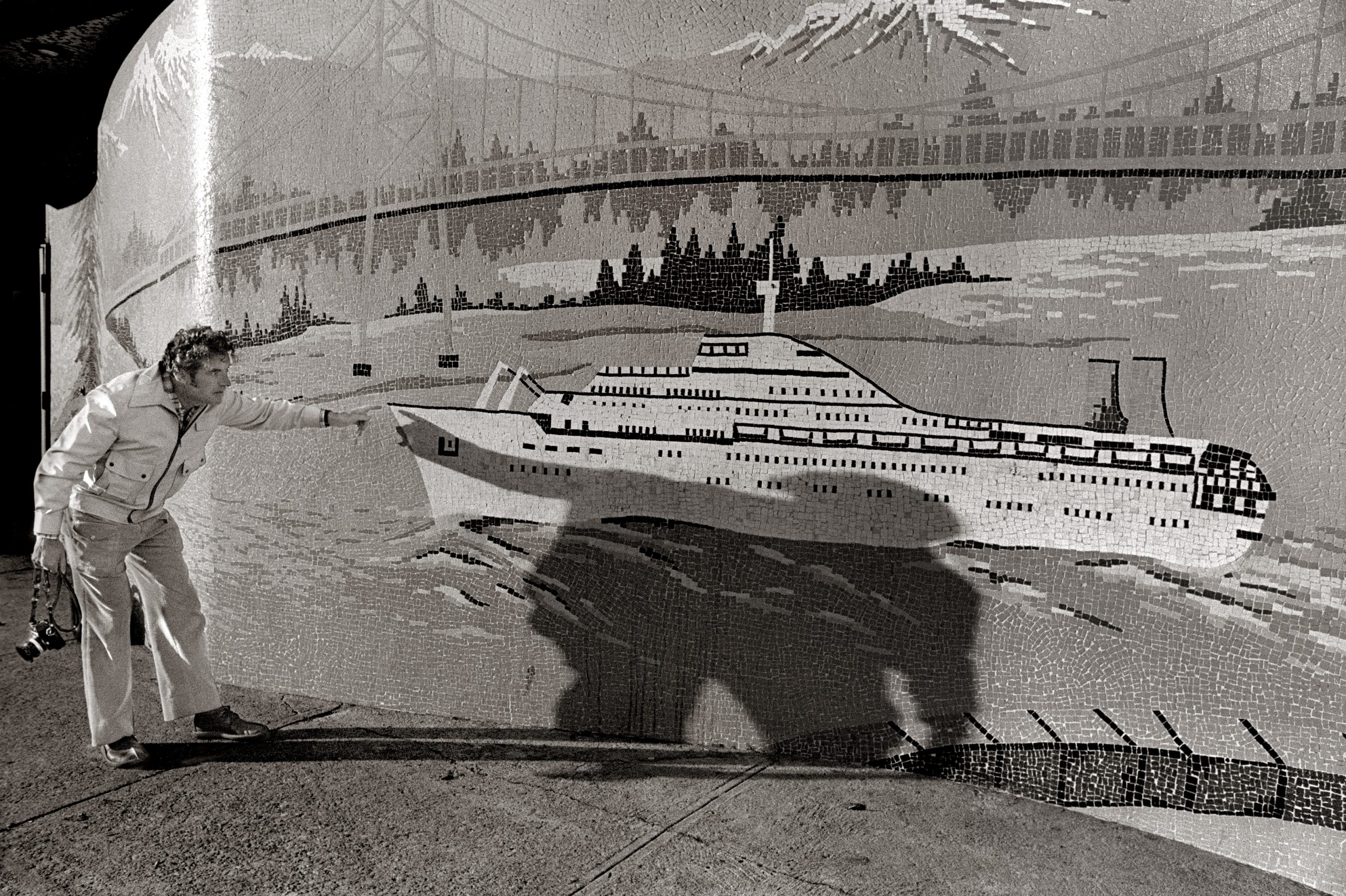

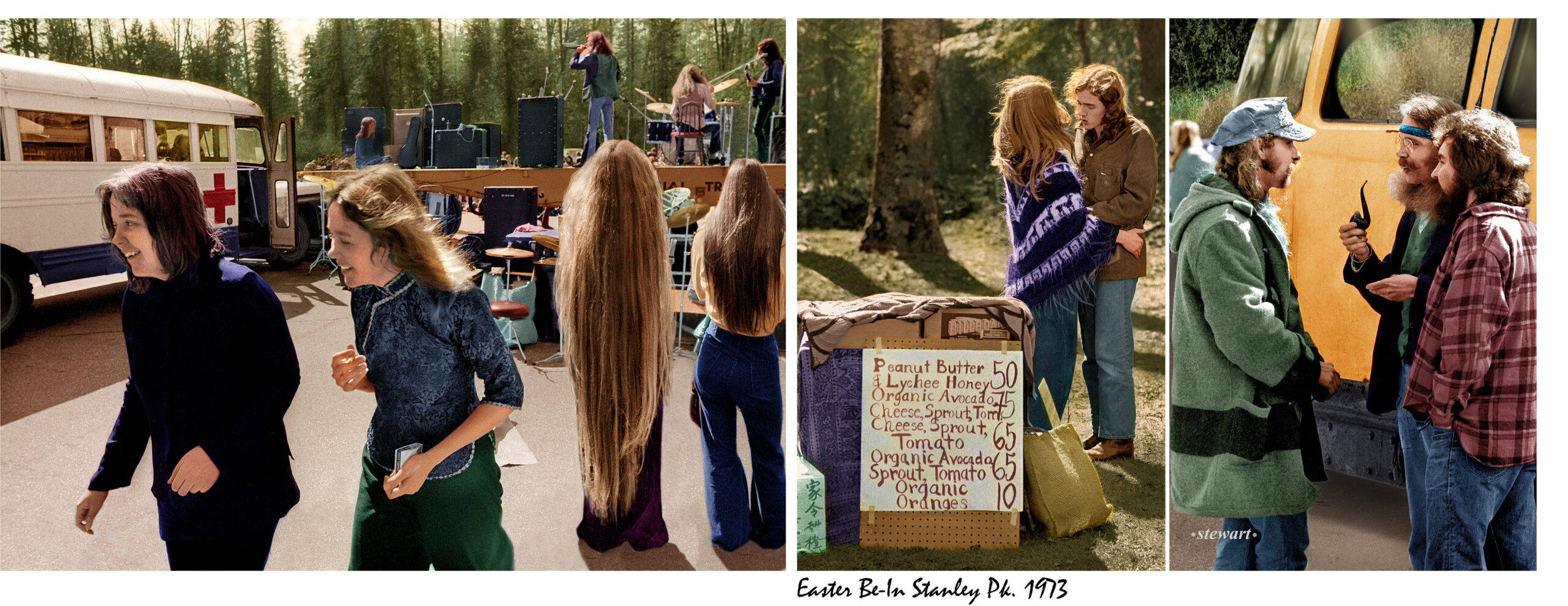

On April 22, 1973, when Bruce Stewart shot these fabulous photos, the Be-In was in its seventh year. About 10,000 people turned up to listen High Flying Bird, Brain Damage, Dandy Tripper Band and One Man’s Family. It was still counterculture, if not as novel as it had once been, and the story made its way out of Vancouver into the Star-Phoenix in Saskatoon and the Windsor Star in Ontario. The biggest issue that year was the traffic jam in the Stanley Park Causeway.

Sax Man is Ross Barrett. Ross, who also played flute and keyboard, was in the psychedelic band Mock Duck, and around the time this photo was taken, was with Sunshyne, playing with Bruce Fairbairn and drummer Jim Vallance.

1974:

In April 1974, A headline in the Vancouver Sun quoted a teen who called the Be-in “kind of boring.”

By 1977, less than a thousand turned out for the April Be-In and the festival moved to Semiahmoo.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

Related: