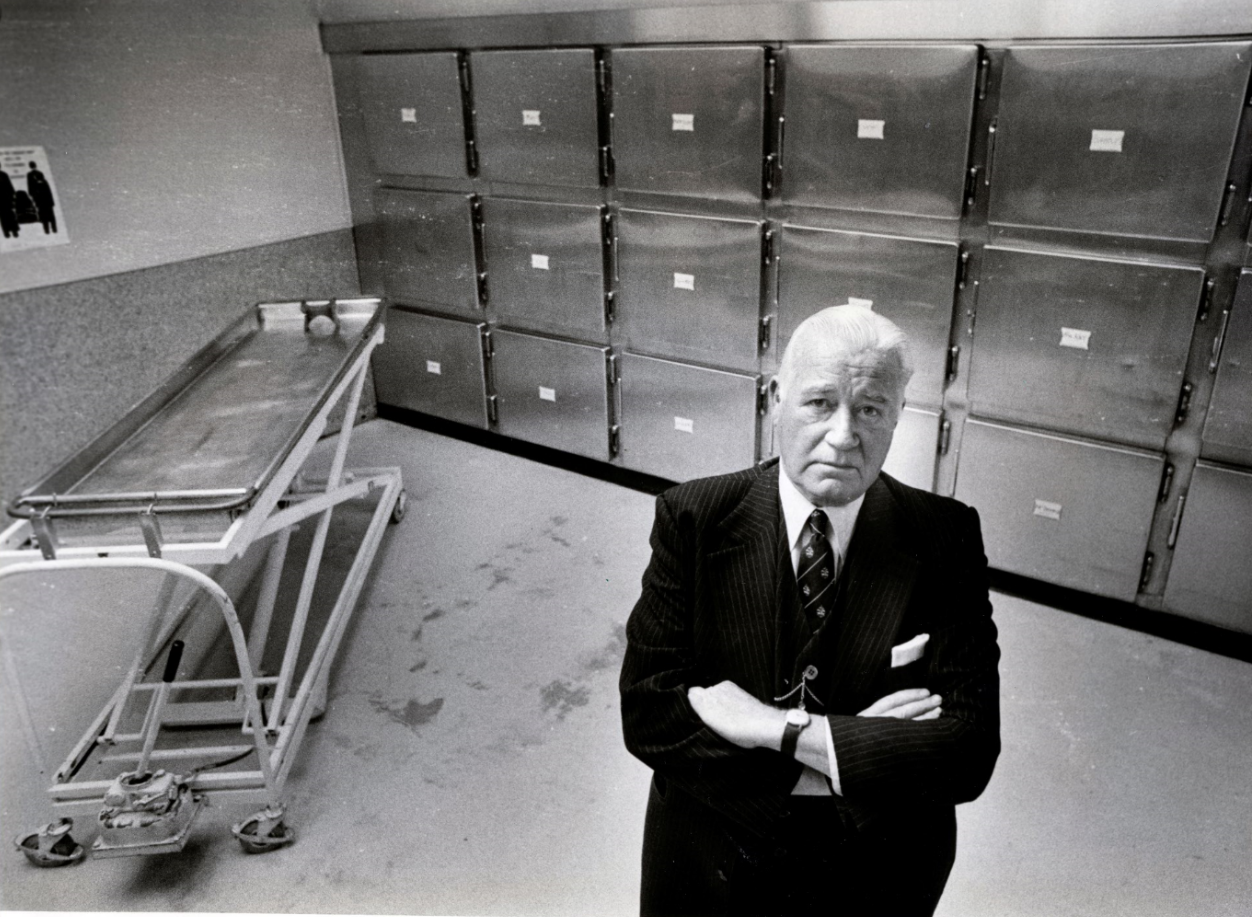

Glen McDonald was easily Vancouver’s most colourful coroner. He called himself the “Ombudsman of the Dead” and served from 1954 to 1980.

If I was able to go back in time and choose six people to interview, Glen McDonald would be high up on the list. I got to know him while I was researching Murder by Milkshake, and his 1985 book How Come I’m Dead? has a prime position on the book shelf above my desk.

McDonald was Vancouver’s coroner from 1954 to 1980. Unlike the star of CBC’s new show Coroner, McDonald was not a doctor. In BC—and I’m quoting from a government job posting—there are 32 full-time coroners with backgrounds in law, medicine, investigation and journalism.

Ombudsman of the Dead:

McDonald, who was a lawyer and a judge, called himself the “Ombudsman of the Dead.” He told people it was his job to find the cause of death in order to help the living, and he did this from his morgue on East Cordova Street (now the Vancouver Police Museum and Archives) where an average of 1,100 bodies passed through each year. He smoked 50 cigarettes a day, drank beer and spirits kept beside forensic specimens in an office fridge, and conducted one or two inquests a week that looked into deaths ranging from shootings and stabbings to drug overdoses and traffic accidents.

Finding Cause of Death:

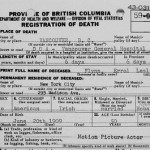

His job was to assemble a jury and determine whether death was natural, accidental, suicide, or homicide. After he retired, he admitted to occasionally lying to priests so that his Catholic victims could be buried in consecrated ground. He’d say he hadn’t reached a conclusion. The funeral would go ahead as if the death was not a suicide and McDonald would sign the death certificate when the body was safely in the ground.

He said his job was to find the cause of death in order to protect the living, and he investigated everything from deaths by shooting, stabbing, and strangulation, to poisoning, suicide, drug overdoses, and death by traffic, rail and boat accidents.

Ironworkers Memorial Bridge

He officiated over the Inquest of 18 men who were killed when the Second Narrows Bridge collapsed while under construction in 1958. And, he was in charge when CP Flight 21 blew up over the BC Interior killing all 52 people on board in 1965.

One of his more famous cases was the death of Aussie actor Errol Flynn in 1959. Flynn, 50, was in Vancouver with his 17-year-old girlfriend trying to sell his yacht Zaca to a local millionaire. He had a heart attack while at a party in the West End and ended up in McDonald’s morgue. (The full story is in Sensational Vancouver).

Murder by Milkshake:

The first time McDonald came across death by arsenic poisoning was in 1965 with the murder of Esther Castellani. The first thing he did was install himself in the science section of the VPL and read everything he could find about arsenic poisoning. As he wrote in How Come I’m Dead? he suspected that Rene Castellani had been at the library some months before, doing exactly the same thing.

My favourite McDonaldism is when he gained national notoriety for calling Bingo Canada’s most dangerous sport. He was referring to the number of seniors who were run over while walking to their weekly games.

McDonald died 23 years ago—on January 23, 1996. He was 77.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.