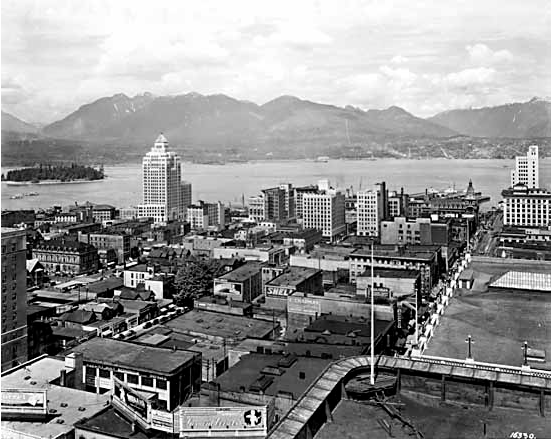

Members of the Town Planning Commission passed a resolution stating that they were not in favour of Deadman’s Island as a site for a proposed museum of Vancouver art, historical and scientific society. It was declared the Coal Harbour site was too inaccessible—Province: April 9, 1932

It continues to amaze me that Stanley Park has survived, despite all the attempts to develop it over the years.

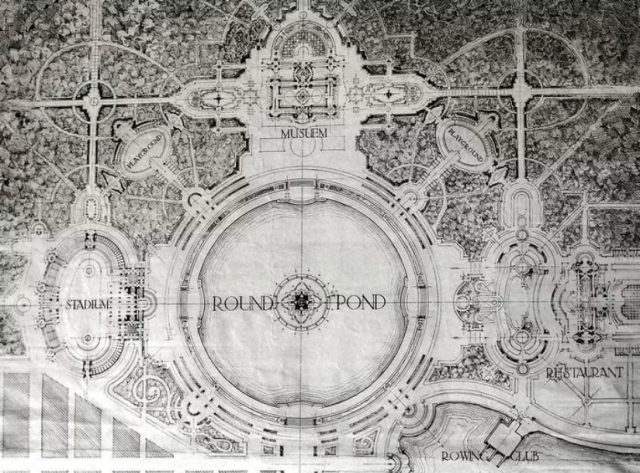

In 1912, there was a push to “transform” Lost Lagoon into Grand Round Pond, with a surrounding museum, stadium and amusement park. There would be ornamental gardens, fountains a children’s playground, library and Georgia Street would be the “Champs-Elysees.”

Fortunately, commonsense prevailed. Said Mayor James Findlay: “Thomas Mawson may be the finest architect in the world, but he cannot put Stanley Park back for us once it is destroyed.”

In the 1960s and ‘70s there were three attempts to turn Seasons Park—the 14 acres at the entrance—into a massive hotel and condo complex.

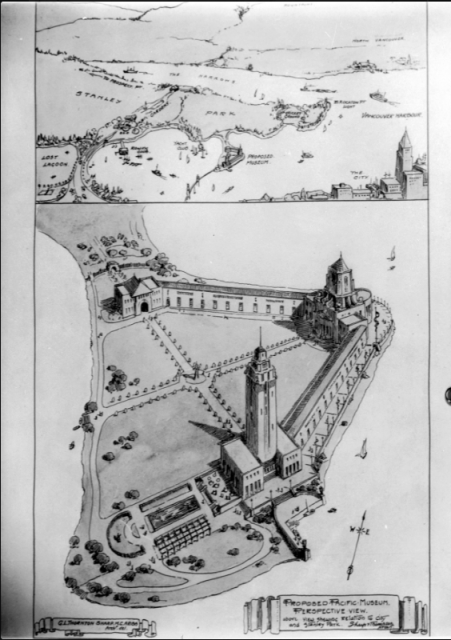

And in the early ‘30s there were plans to plop a castle-like museum building complete with citadel, on Deadman’s Island.

Measuring just 3.8 hectares, and attached to Stanley Park by a short causeway, Deadman’s Island, or Skwtsa7s (meaning island), has an amazing history. It was a battle site. It was an indigenous burial ground, where the dead were placed in wooden coffins and buried both in the ground and up in the trees. When small pox hit, it was used to quarantine the victims, and later bury those who didn’t make it. The land has also claimed British Merchant seaman, people from Moodyville, victims from the Great, and workers killed while extending the CPR line from Port Moody to Coal Harbour. One article says West Vancouver’s Navvy Jack is buried there.

In 1930, the federal government leased the island to the city. Shortly after, the city commissioned Sharp and Thompson Architects to draw up designs for Pacific Museum. It didn’t get very far, and in 1944, became the site of HMCS Discovery Naval Reserve.

When the 99-year lease came up for renewal in 2007, Mayor Sam Sullivan tried to make it publicly accessible. He told the Globe and Mail he wanted a ferry service from downtown and a museum that could preserve and display the maritime heritage of native people.

The Musqueam just wanted it back.

Except for an open house once or twice a year, which I always seem to miss it, the site remains off limits.

Sources:

- Jason Vanderhill’s Illustrated Vancouver

- Vancouver Public Library’s Special Collections

- Globe and Mail, April 27, 2006

- Vancouver Sun, December 28, 2018

- Vancouver Courier, March 30, 2010

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.