Janet Stewart was going through her mother Edna’s things after she passed away recently and came across four sketches by Frits Jacobsen. They showed various Vancouver buildings in the late 1960s. Janet googled his name, came across a story by Jason Vanderhill on my blog, and kindly sent me photos.

Hornby and Nelson:

I posted Jacobsen’s drawing of the corner of Hornby and Nelson Streets from 1969 on my Facebook page Every Place has a Story. Barry Leinbach commented that in 1968 he was working at a part time job in the parking lot across the street (now part of the law courts). He saw smoke coming out of the house on the corner. “I phoned the fire department and fortunately they saved most of the house, but they never repaired it.” At the time, Barry studied at King Edward campus, which burned down in 1973.

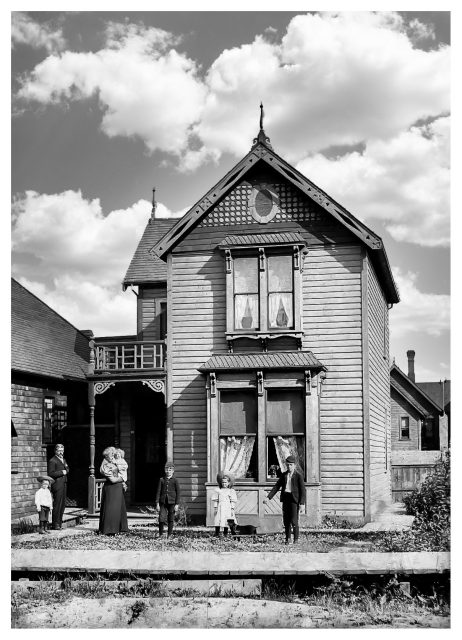

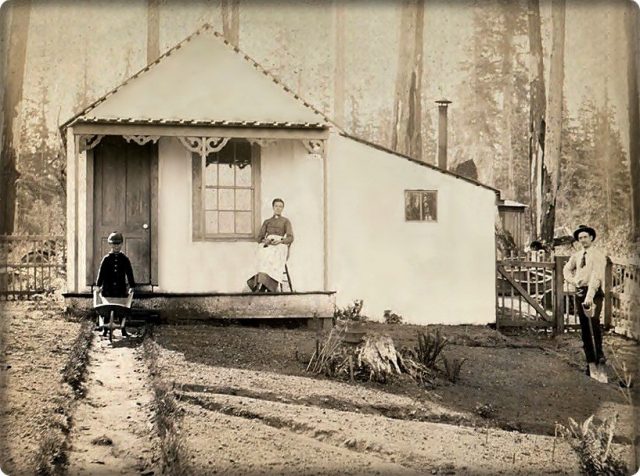

It was the first time that Heather Lapierre had seen the sketch. She said that the house was once 918 Hornby Street and that her great grandparents lived there when they came to Vancouver in 1893. I jokingly asked if she had a photo with the family standing on the front porch. Turns out that she did.

“I had no idea that the house was still there in the 70’s. I wish I had known and could have seen it,” she says. “It was only when my mother passed in 2000 that I inherited all these photos that nobody had ever talked about or showed me, many of which are unlabeled and remain a mystery.”

False Creek:

Heather also sent a photo of her paternal great grandparents first home. “It was just listed in the directory as False Creek, but on the reverse, written by my grandmother, it says, ‘first home of James and Ellen Findlay. Bruce Findlay with the barrow. False Creek 1889’.” James beat out LD Taylor in 1912 to become mayor of Vancouver. “When he was mayor, James Findlay lived at 1428 Robson and my father was born in that house. I have never been able to find a photo of the Robson Street house. It would have been torn down to make way for the Landmark Hotel – now also demolished,” she says.

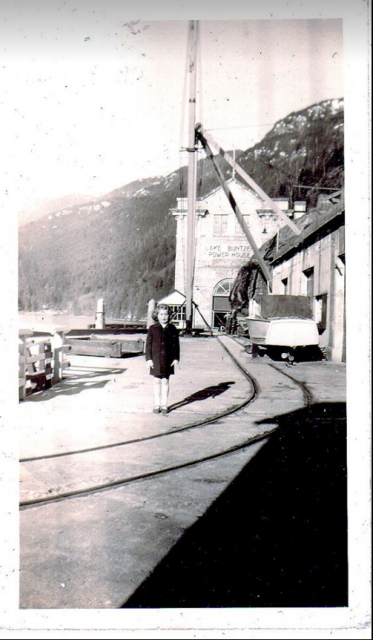

Buntzen:

Heather’s grandfather Matt Virtue was one of the first powerhouse operators at Buntzen on Indian Arm and she was born there. Her story is in Vancouver Exposed.

It makes me wonder how many family albums are holding photos like these. If you have one of an early Vancouver building or event and know where it was, please send a copy to eve@evelazarus.com and we’ll add it to Vancouver’s history.

© Eve Lazarus, 2022

Related: