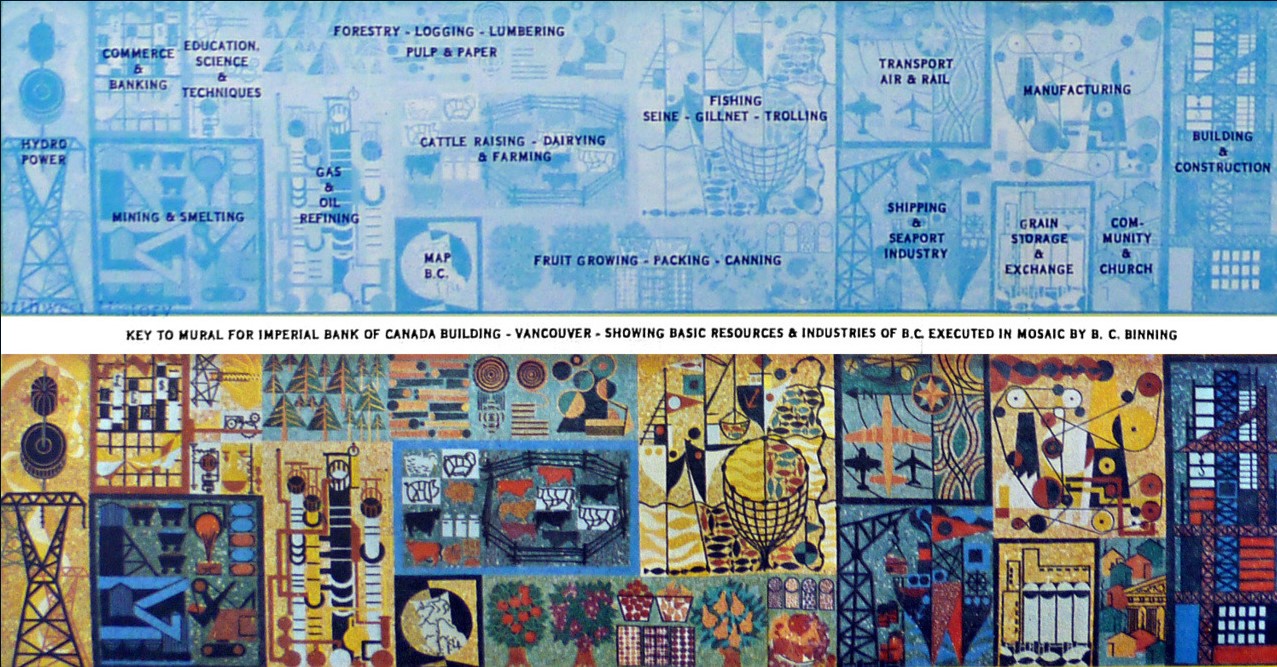

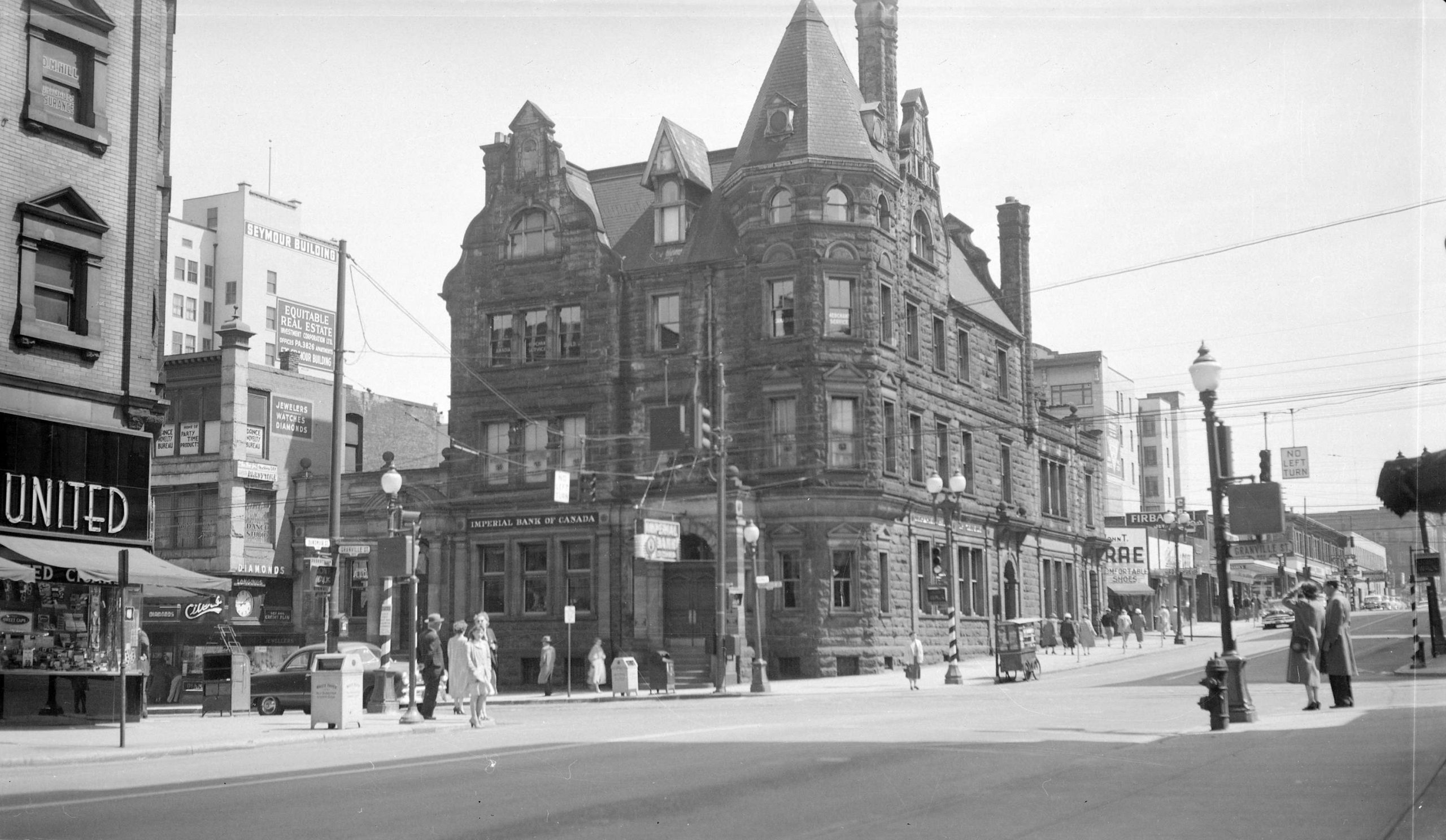

The Imperial Bank of Canada opened its new building on April 21, 1958 at Granville and Dunsmuir Streets. It featured this stunning mural by BC Binning. The building is now occupied by a Shoppers Drug Mart, but the mural is still there.

From Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

The Mural:

Next time you’re downtown and have a mascara emergency or need some aspirin, drop into the Shoppers Drug Mart at Granville and Dunsmuir. Once you hit the cosmetics area, you might just forget what you came in there for, because opposite the front entrance and right above the gift cards is one of the hidden wonders of Vancouver—a stunning tile mosaic created by legendary artist BC Binning in 1958.

Although it’s probably best not to, if you go up to the second floor, you can actually touch one of the 200,000 pieces of Venetian glass that make up this massive mural that dominates the entire length of the wall. Binning, an artist who taught architecture, was commissioned by the Imperial Bank of Canada to celebrate the province’s booming resource-based economy, from hydroelectricity and forestry to shipping and agriculture, with a “key” to help interpret it.

Made in Italy:

Binning spent more than three months in Venice overseeing its preparation. He climbed a ladder a few times each day to look down at the growing tile and marble mosaic for the overall effect. When the greens weren’t as vibrant as he expected, he had the tiles changed. When the mosaic was finished—all 500 square feet of it—it was shipped to Canada in 12 boxes, to be reassembled on the wall like a giant jigsaw puzzle.

McCarter Nairne (the architects behind the Marine Building, Devonshire Hotel, and Georgia Medical and Dental Building, designed the mid-century building which featured terrazzo floors, polished granite and marble columns.

From Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus