There is a chapter in Sensational Vancouver called West Coast Modern which explains the connections between artists and architects and the West Coast Modern movement in Vancouver.

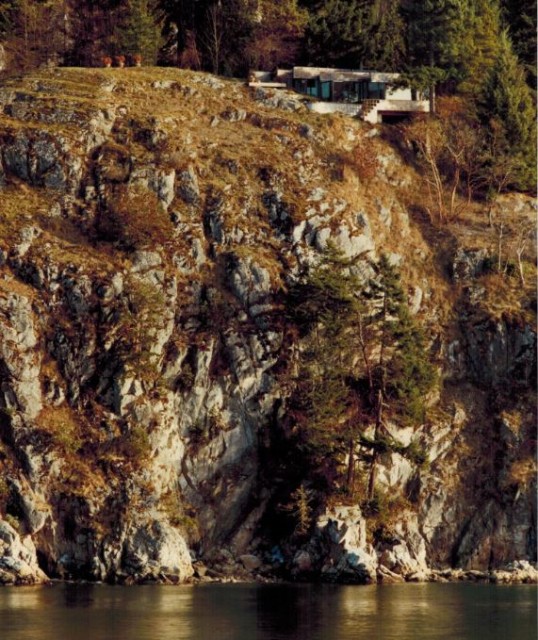

Last week I wrote about Selwyn Pullan’s photography exhibition currently on display at the West Vancouver Museum. I focused on his shots of West Coast Modern houses now almost all obliterated from the landscape.

But Selwyn also did a lot of commercial photography and one of his largest clients was Thompson Berwick Pratt, the architecture firm headed up by Ned Pratt who hired and mentored some of our most influential West Coast Modern architects. Arthur Erickson, Ron Thom, Paul Merrick, Barry Downs and Fred Hollingsworth all cut their teeth at TBP, and BC Binning consulted on much of the art that went along with the buildings.

Ned Pratt’s crowning achievement was winning the commission to design the BC Electric building on Burrard Street—a game changer in the early 1950s. While the building is still there, now dwarfed by glass towers and repurposed into the Electra—a few of the firm’s other creations are long gone.

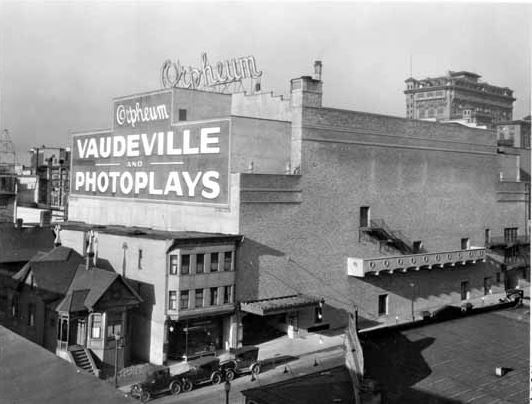

There was the Clarke Simpkins car dealership built in 1963 on West Georgia that demonstrated Vancouver’s growing fascination with neon.

Our love for neon also showed up in the former CKWX headquarters at 1275 Burrard Street. According to the Modern Movement Architecture in BC (MOMO) the building won the Massey Silver Medal in 1958. “This skylit concrete bunker was home to one of Vancouver’s major radio stations until the late 1980s. The glassed-in entrance showcased wall mosaics by BC Binning, their blue-gray tile patterns symbolizing the electronic gathering and transmission of information.”

The building is long gone, replaced by a 20-storey condo building called The Ellington in 1990.

I wonder what happened to the murals?

The Exhibition runs until July 14.

- Top photo: Clarke Simpkins Dealership, 1345 West Georgia. Built 1963, demolished 1993. Selwyn Pullan photo, 1963.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus

Rapidly disappearing:

Rapidly disappearing: