On September 10, 1968 the Vancouver International Airport opened a spanking new terminal building to handle all domestic, US and international flights. It was one of the few airports where aircraft could pull up to gates attached to the terminal and where passengers could load and unload via a bridge.

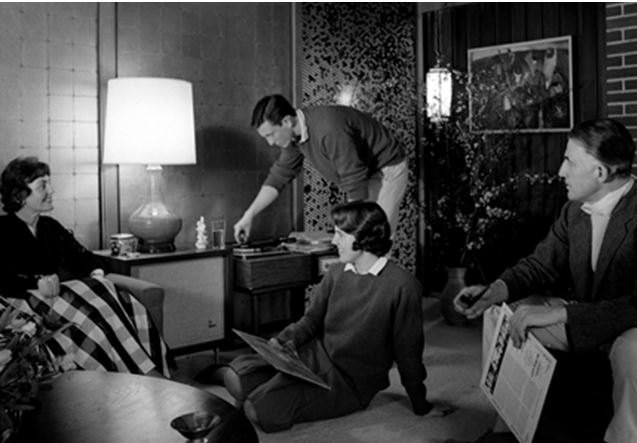

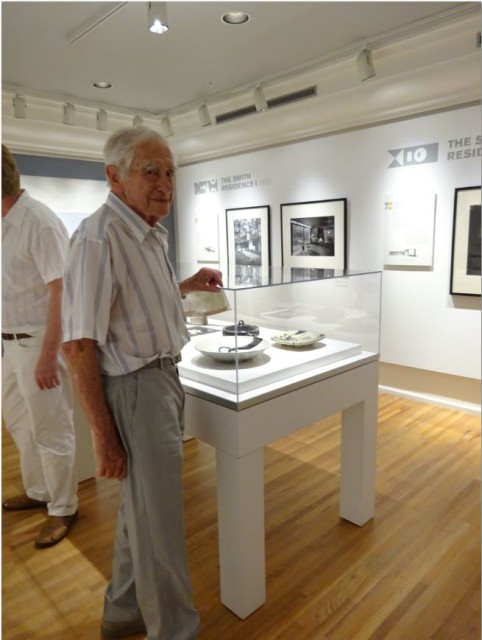

Designed by Zoltan Kiss:

The building was designed by Zoltan Kiss of Thompson Berwick Pratt, the firm that served as an incubator for such other up-and-comers as Arthur Erickson, Ron Thom, Barry Downs and Fred Hollingsworth and designed buildings such as the game-changing BC Electric building on Burrard Street in 1957.

The terminal had the modern design, clean lines and open spaces common to mid-century architecture at the time. It screamed jet-setting technology and speedy travel.

New terminal:

If you’ve taken a plane from Vancouver to any other point in Canada—you’ve walked through this terminal. You’ve also likely noticed the two large air-intake towers that flank it. These concrete towers were an engineering feat back in 1968 and replaced the old system which had the air intake in the roof. When the wind would blow the wrong way, employees and passengers would complain about the overpowering smell of aviation fuel.

“I remember how large and modern it was compared to the old (now South) terminals,” says Angus McIntyre. “You could drive your car up to the departure level, park and pay 25 cents at a meter. Hah!”

Opened in 1931:

YVR officially opened in 1931 when the City of Vancouver invested $600,000 in a runway and a small wood framed building topped by a control tower after US aviator Charles Lindbergh refused to visit because there was “nothing fit to land on.”

Big changes happened in the 1960s after the City sold the Airport to the Department of Transport. By 1968 the airport sat on more than 4,000 acres of land, and the terminal building, which cost $32 million, served close to two million passengers in its first year of operation.

Half a century later, more than 24 million passengers pass through YVR each year.

Related:

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.