Arthur Erickson is one of Canada’s most famous architects, yet his own house and garden ranks #8 on Heritage Vancouver’s top 10 endangered sites for 2014.

Arthur Erickson’s fingerprints are all over some of Metro Vancouver’s most iconic buildings—the Museum of Anthropology, Simon Fraser University and dozens of residential houses.

Unusual for an architect, Erickson chose not to design his own house, but bought a large corner lot in Point Grey with a 1924 cottage and garage for $11,000 out of which he created the 900-square-foot home where he lived for the next 52 years.

“Architecturally this house is terrible, but it serves as a refuge, a kind of decompression chamber,” he told author Edith Iglauer*.

He replaced the walls with sliding glass and connected the buildings, adding a bathroom and a kitchen. He played with different materials—leather tiles on the bathroom wall, wall tiles in Italian suede in the living room, and Thai silk in the study—and then he turned his attention to the garden.

Erickson bulldozed the English garden, dug a hole for the pond and used the dirt to make a hill high enough to block the view of his house from his neighbours.

“Everybody in the neighbourhood thought I was excavating to build a house, and chatted with me over the picket fence, very happy to believe that they were no longer going to have a nonconformist garage dweller among them,” he told Iglauer*.

He planted grasses and rushes from the Fraser River, pine trees from the forest, put in 10 different species of bamboo, and added rhododendrons, a dogwood, and a persimmon to the existing fruit trees. He was known for throwing lavish garden parties that drew a guest list ranging from Pierre Trudeau to Rudolf Nureyev

Barry Downs lived in the Dunbar area at the time and knew Erickson quite well.

“We both had little ponds full of fish and one day Mary and I gave him a turtle,” said Downs. “He phoned me up and said ‘get over here your turtle is eating my fish!’”

Down’s told him that was impossible, the turtle had a mouth the size of Erickson’s thumb.

“I went over and sure enough there’s a fish sticking out of its mouth,” said Downs, adding that yes he took the turtle back.

“Arthur was ruthless. He had a BB gun and would shoot at the herons that would come in and land and eat his fish. Once he told me that he shot through the neighbour’s window accidently,” says Downs.

Downs says the impressive Japanese-inspired marble terrace panels in the garden are the toilet stalls from the old Hotel Vancouver.

Erickson may have been a talented architect but he was hopeless with finances. By 1992 he had racked up over $10 million in debt and was on the verge of losing his house. A group of friends which included Peter Wall, who took over the $475,000 mortgage, placed the house and garden in the hands of the Arthur Erickson Foundation. Erickson lived there until his death in 2009.

*Iglauer, Edith. Seven Stones: A Portrait of Arthur Erickson, Architect. Harbour Publishing, 1981.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

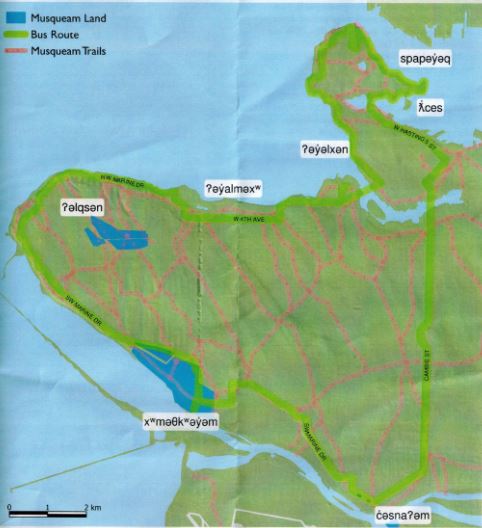

As recently as 2011, the City of Vancouver issued a building permit to Century Holdings and it looked like the Marpole Midden would be turned into a 108-unit condo development. But work stopped when the remains of an adult and two small children were discovered, kicking off a Musqueam vigil that went for over 200 days.

As recently as 2011, the City of Vancouver issued a building permit to Century Holdings and it looked like the Marpole Midden would be turned into a 108-unit condo development. But work stopped when the remains of an adult and two small children were discovered, kicking off a Musqueam vigil that went for over 200 days.