Lurancy Harris and Minnie Millar became the first two women police officers in Canada when they were hired by the VPD in 1912

The following is an excerpt from Sensational Vancouver.

Joins VPD:

Lurancy Harris was a 48-year-old seamstress from Nova Scotia had moved to Vancouver in 1911 and rented a small apartment on Robson at Howe. One day she was flipping through a newspaper when an ad caught her eye. The Vancouver Police Department was looking for “two good reliable women” to form the nucleus of a women’s protective division centred around issues of morality and protecting the safety of wayward women and children.

She and Millar were sworn in as fourth class constables, the lowest rank in the department with a salary of $80 a month. The women were given full police powers and thrown into the job with no training, no uniform and no gun.

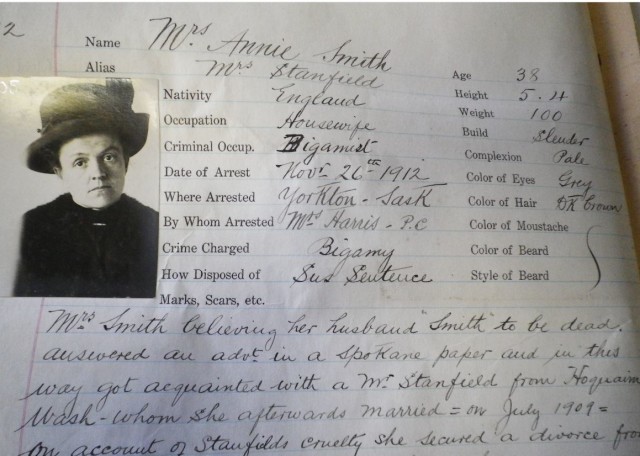

First Arrest:

Lurancy made her first arrest five months after she was hired. In the Prisoner Record book of 1912 at the Vancouver Police Museum, Annie Smith, 38, alias Mrs. Stanfield, a bigamist from England told police that she believed that her husband was dead and had answered a personal ad in a Spokane newspaper, met and then married a Mr. Stanfield. On account of his “cruelty” she fled to Vancouver with her two small children. Stanfield found her, found the original Mr. Smith and the two men went to police. While Annie was found “technically guilty” she was given a suspended sentence “on account of the troubles and suffering she had endured.”

Arrest of Lorena Mathews:

Lurancy’s big break came a month later when she was given the task of escorting Lorena Mathews on the train back to Oklahoma after she was arrested in Vancouver. Mathews had bolted across the continent with her two children and Jim Chapman, her 25-year-old black lover who was suspected of helping her murder her much older husband. Chapman was convicted, Mathews was acquitted, and Lurancy got a promotion.

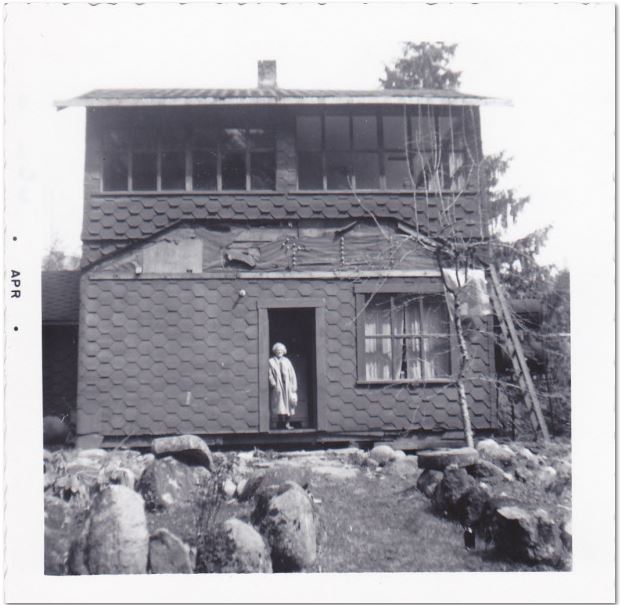

In 1916, Lurancy bought a lot on Venables Street in East Vancouver. She had a small craftsman house built and planted a monkey tree. The house is still there, a second floor was added in 1983, and the monkey tree towers over it all.

By all accounts, Lurancy had an amazing career. In 1924 she was promoted to inspector, although she was kept at the pay scale of a sergeant. She retired in 1928 aged 65.

While more women gradually joined the police force, things were slow to change. Women did not get uniforms until 1947, they were not allowed to drive police cars until 1948 (they went to calls on foot or took the street car), and it wasn’t until the 1970s that women had the right to carry firearms and were assigned to the same duties as their male counterparts.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

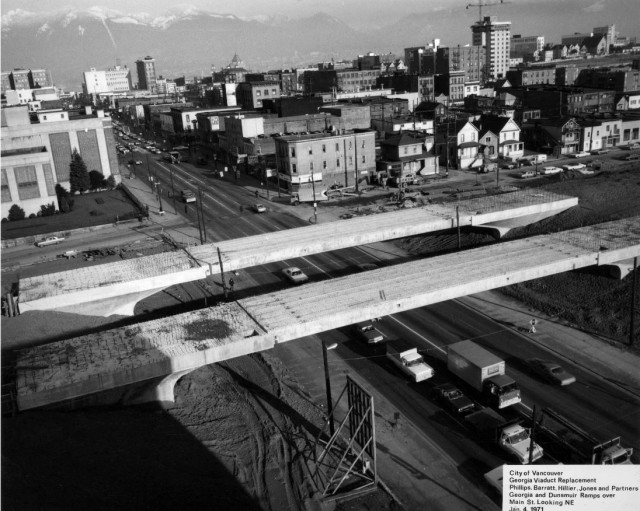

Vancouver Archives

Vancouver Archives