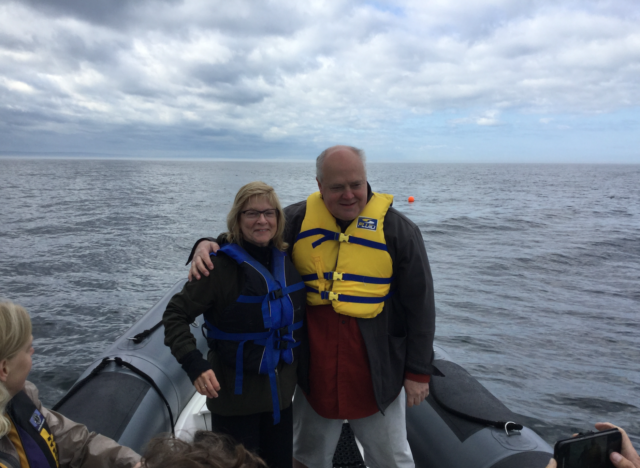

In August 2019, I was sitting on a Zodiac in the middle of the St. Lawrence River piloted by a French Canadian marine biologist. The trip was arranged by Hugh Verrier, and we were right above the wreck of the Empress of Ireland, a CPR-liner that sunk in 14 minutes after being rammed by a Norwegian coal ship in 1914. It’s now an underwater graveyard for more than 800 souls.

Hugh is based in New York and heads up one of the world’s largest law firms, but he is originally from Montreal, and has a summer property near Rimouski, close to where the Empress of Ireland sank. Hugh swims in the St. Lawrence River most summers and has always known about the tragedy, but in recent years he has developed a fascination for the story of survivor Gordon Charles Davidson.

Gordon Charles Davidson:

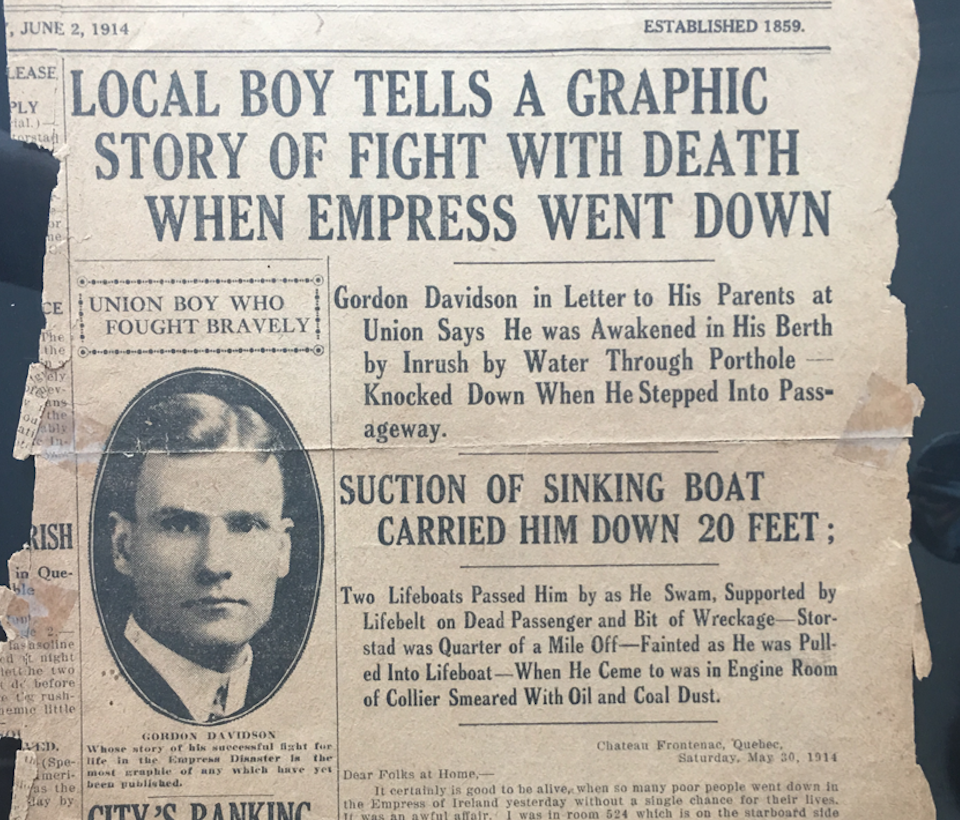

Davidson was a PhD candidate who lived in Vancouver when he wasn’t studying at UC Berkeley in San Francisco. He had reportedly survived the sinking of the Empress by swimming 6.5 kilometres (4 miles) to shore. When Hugh looked into this, experts told him this wasn’t possible—not at that time of year and not for that distance. But Hugh wanted to make sure. He wanted to verify the information that had been repeated in newspapers articles and regurgitated in books and even at Davidson’s own memorial service more than a hundred years ago. Whatever happened, Hugh wanted to set the record straight.

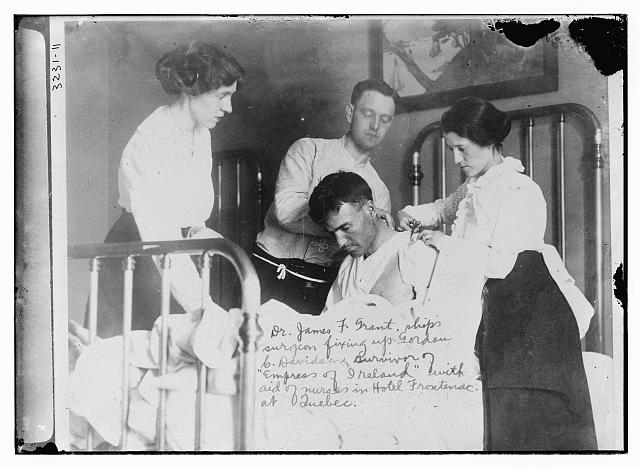

Hugh had hired me two years earlier to research the story of Gordon Davidson, one of the few survivors from Vancouver. In an email to me, he attached Davidson’s 1922 obituary, an article about his miraculous swim to shore, and a photo of him receiving medical treatment at the Château Frontenac following the shipwreck. “I have not found any record of him speaking or writing about swimming to shore,” Hugh wrote. “He did not have any children. So, this is not going to be easy to find out about.”

Staggering Loss of Canadian Life:

I was surprised that I’d never before heard of the Empress of Ireland, because the loss of Canadian life was truly staggering. More passengers died that night (836), then died on the Titanic (832) in 1912, or on the Lusitania (788) two years later.

I was eventually able to locate one of Davidson’s descendants and track down the real story of Gordon’s survival. He had written a letter to his parents immediately after his rescue.

Davidson did not swim to shore, the story came from the wild speculations of a Province newspaper reporter and later went around the world as fact.

Myth Busting:

I was curious how many other stories told about the Empress of Ireland were also myths, and it turns out there were quite a few. A large part of the book is righting those wrongs. Another focus of the book is telling the stories of the survivors as some went on to fight in the first world war, while others took up homesteading on the Prairies, and a few became successful entrepreneurs.

Thanks to a Canada Council grant, I was able to travel across the country to visit Rimouski, as well as various archives and museums and interview descendants of the survivors.

The Western Canada Connection:

While researching Gordon’s story, I was surprised by how many connections there were to Western Canada—65 people booked through the Vancouver office alone, and only a few came back. Arthur Delamont, a 22-year-old from Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan was part of a 161-member Salvation Army delegation travelling to an International Congress in London where he was playing in the staff band. Arthur lost his brother in the tragedy and later moved to Vancouver where he founded the Kitsilano Boys Band and taught Jimmy Pattison, Bing Thom and Dal Richards, among hundreds of others. Delamont Park in Kitsilano is named for him.

The Empress of Ireland carried more than 117,000 people between England and Canada from 1906 to 1914. A million or so Canadians can trace their roots back to an ancestor who came to Canada on this ship.

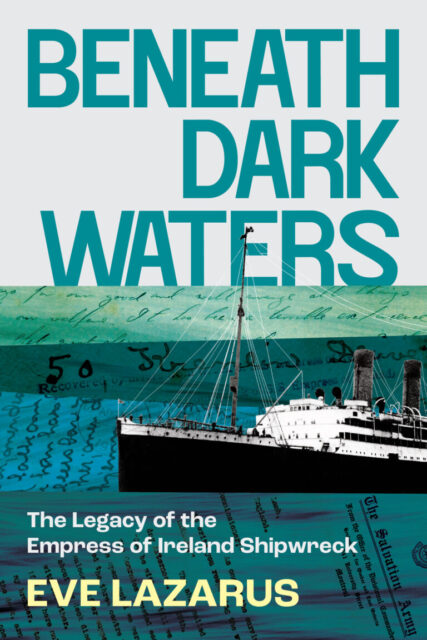

Copies of my new book, Beneath Dark Waters: The Legacy of the Empress of Ireland Shipwreck, are available through all the usual online sources, through my publisher Arsenal Pulp Press, or from any independent bookstore across Canada

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.