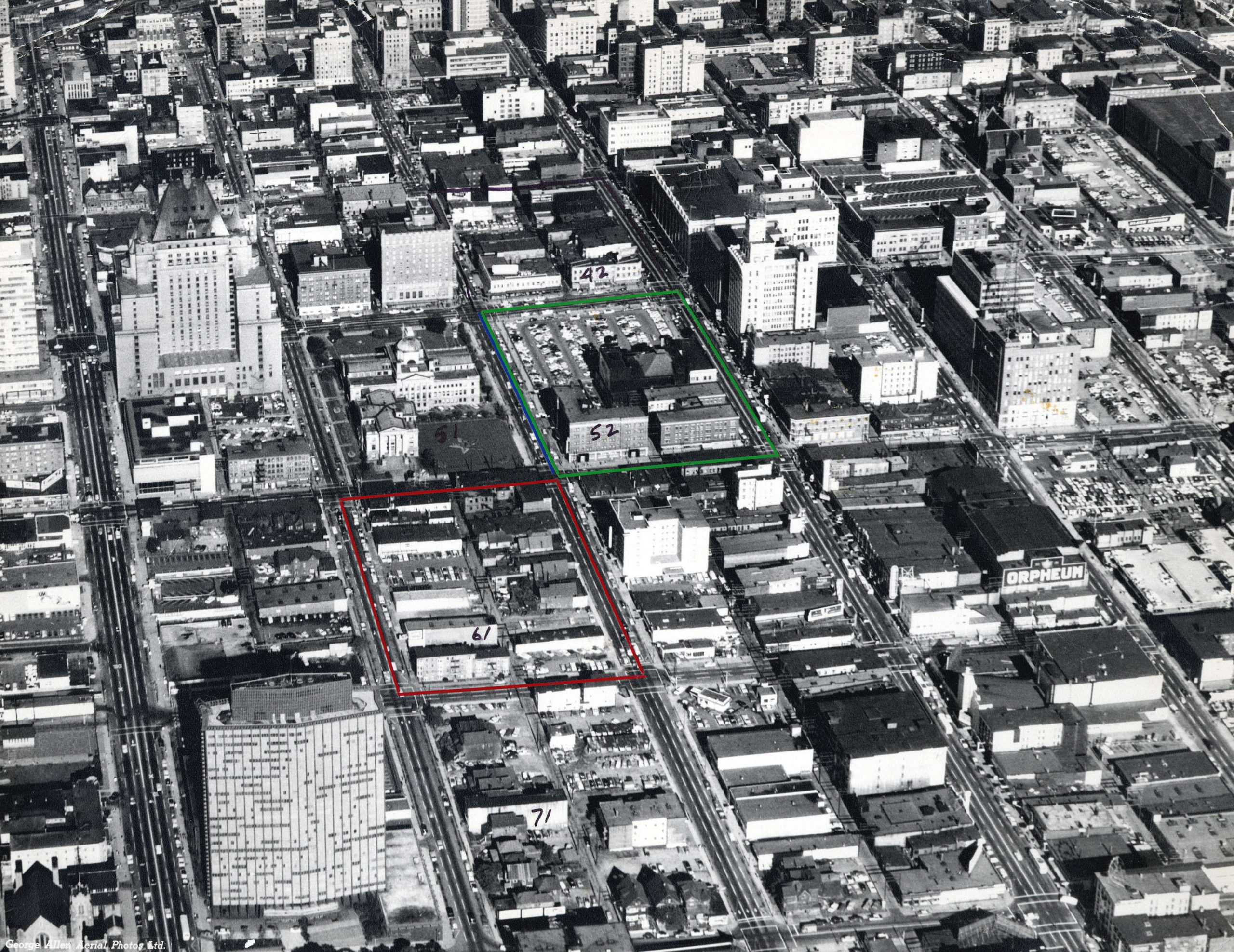

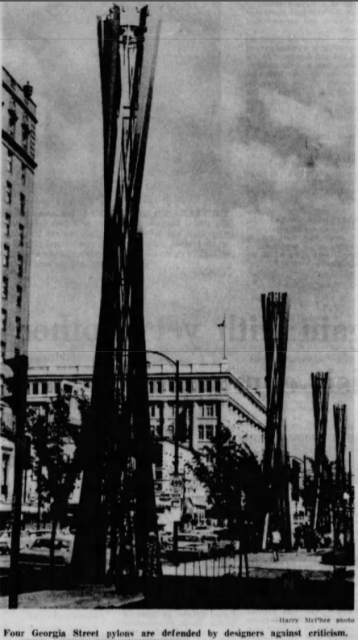

If you lived in Vancouver in the late 1960s, you’ll likely remember the four bizarre red Georgia Street pylons. The pylons ran from Granville to Howe Streets between July 1967 and December 1969.

According to a news media release at the time: “The 60-foot towers, symbolic of giant torches, a traditional heraldic device, are a fitting expression for Canada’s 100th birthday.”

Reaction:

Not surprisingly, the pylons which ran between Granville and Howe Streets, brought out intense emotions. Mayor Tom Campbell thought they looked like “crashed airliners.” He took a bunch of reporters to look at them in the Cambie Street city works in his city-paid limousine and told them: “This is a scrap dealer’s field day, we bought $32,000 worth of junk.” “Tom Terrific,” as the mayor was not affectionally known as, added that it cost taxpayers “$100 a foot.”

Centennial Committee:

The Pylons which were organized through the Vancouver centennial committee, cost $32,000 (over $270,000 in today’s dollars). Designed by structural engineer Boguslaw Babicki and industrial designer Rudy Kovach, they were roughly the size of a four-storey building. Made from steel pipe and lit by 44 spotlights and a dozen 1.5 million-candle-power searchlights, each pylon was decorated with twelve 60-foot strips of nylon material. Each one weighed in at 3,000 pounds and was set in concrete footings.

“I predict that they’ll be the most distinctive thing about Vancouver this summer for tourists and citizens alike, and I’ll bet you they’re used again with different decorations,” Rudy Kovach told the Province. Well, sorry Rudy, they weren’t.

Sold off:

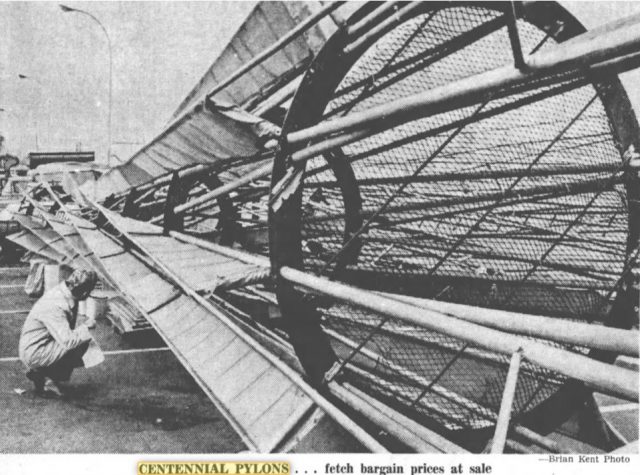

Ben Wosk picked up all four pylons for under $3,000. He bought them for a $10 million development at Whistler (which never eventuated). Wosk outbid five others including Arnold Schuck, who wanted to turn the pylons into giant scissors to advertise his furniture business.

An anonymous buyer paid $10 each for four steel Maple Leaf frames with light sockets that were attached to the pylons.

So, the question is – where are the pylons now?

With thanks to Angus McIntyre who suggested the story and provided most of the research.

Sources:

Vancouver Sun, June 27, 1967 “’$100 a Foot for Junk,’ moans Mayor of Towers”

Province, July 5, 1967 “You Can’t Measure Art”

Vancouver Sun, December 7, 1971 “Bleachers bought for fencing.”

Province, December 8, 1969 “A different kind of fire sale.”

© Eve Lazarus, 2022