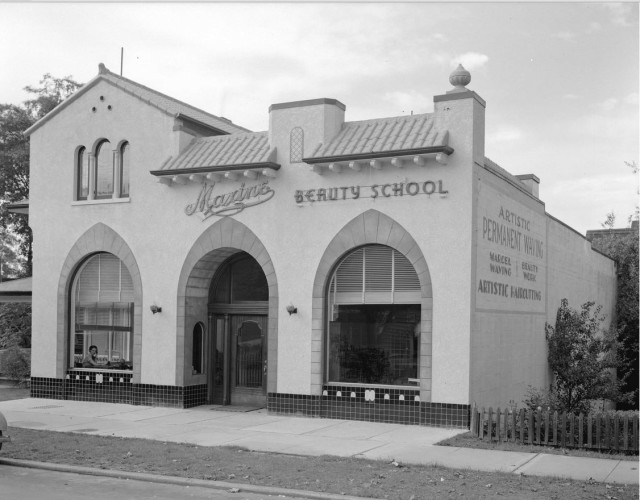

Il Giardino: The last time we were here, the server was so overcome by the beauty of a group of women sitting near us that he broke into an aria. Turns out that when he wasn’t waiting tables he was singing in an opera. Just one of the pleasant surprises at this downtown restaurant, which doesn’t have a view but does have a fabulous outdoor garden terrace in the summer and, in winter, a cozy villa atmosphere….” Eve Lazarus, Frommer’s with Kids Vancouver, 2001 “Get a Babysitter.”

Hornby Street:

Umberto Menghi turned Leslie House into an Italian restaurant in 1973. The following year he created La Cantina next door, and in 1976, he opened Il Giardino on the other side, and somehow managed to operate all three restaurants.

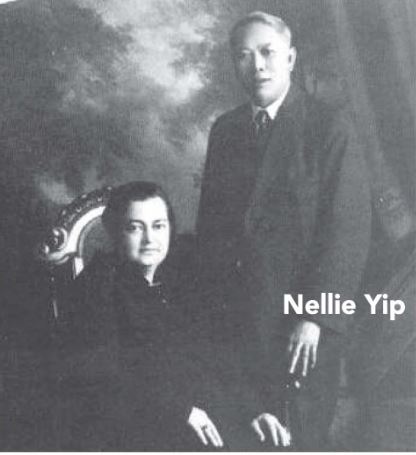

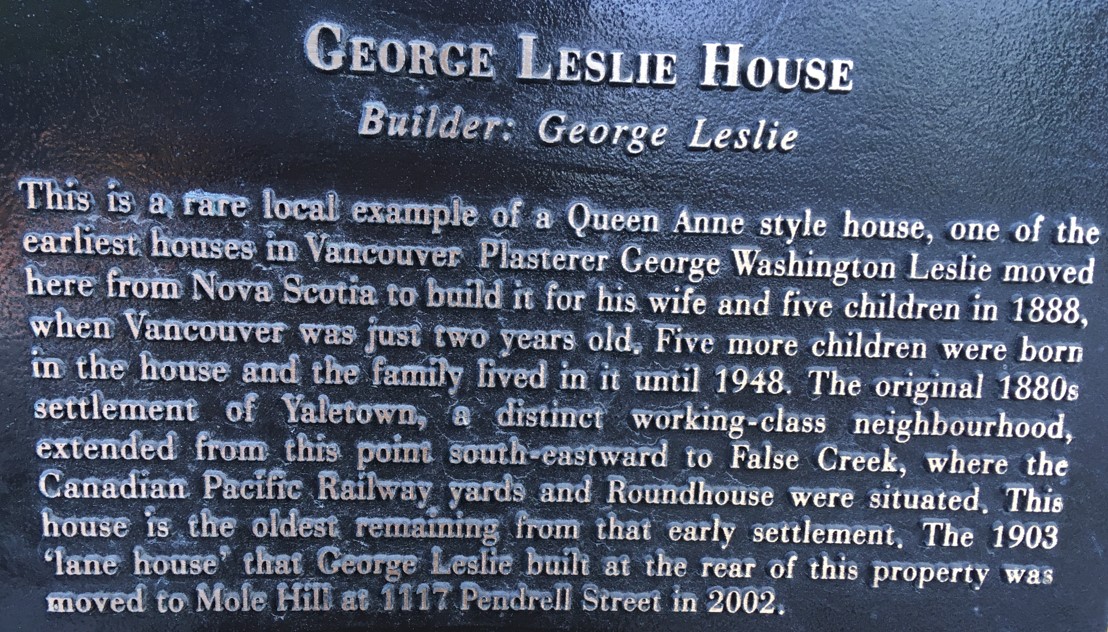

The yellow house was built in 1888 as a family home by and for George Washington Leslie, a plasterer and transplant from Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Leslie moved to Vancouver to help rebuild the city after the Great Fire two years earlier, and built the Queen Anne for his wife and five children.

And, as a man who was more than a century ahead of his time, in 1903, George added a sweet little lane house to the back of his property.

The Leslie family lived on Hornby Street until 1947. For the next 20 years the house operated as Wilhemina Meilicke’s interior designer studio and home. Later, it became a fashion studio called Mano Designs and received its bright yellow coat of paint. Umberto Menghi bought the house in 1972 and operated Il Giardino until 2013.

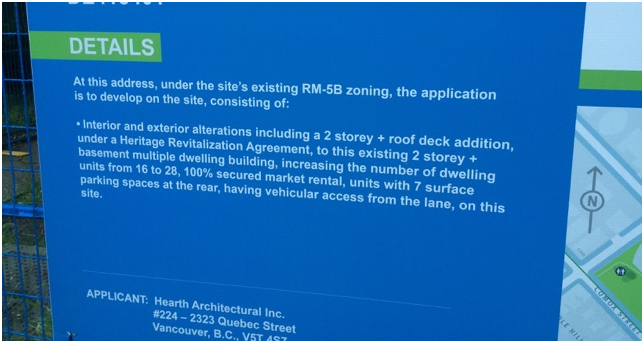

Menghi donated the lane house to the Vancouver Heritage Foundation, and it’s been part of the Mole Hill heritage house landscape on Pendrell Street near Thurlow since 2002. Menghi’s former restaurant was replaced by a 39-storey condo tower called the Pacific. Miraculously, the Leslie House survives among a sea of condo buildings around the corner from its original location. It’s now the home for Blenheim Realty and a couple of property developers.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.