Last week’s blog on Kitsilano featuring Bruce Stewart’s photos, brought back memories and a healthy does of nostalgia from those of you who were lucky to have known Kits in the ‘70s.

In this week’s blog I’m delighted to bring you photos from Angus McIntyre, Gord McCaw, Peter Dobo and a couple more from Bruce, interspersed with your comments.

Says Angus McIntyre: “Sam Angel the “Mattress Man” was across the street. He paid for the first New Year’s Eve free rides in 1974, and got his name on the front of every bus.”

“This view was taken in the mid-1970s as the City of Vancouver converted street lighting from incandescent (on the left side of the street) to mercury vapour (on the right side),” says Angus. “This shows how the night time appearance of the city changed. But little did we know what was in store a few years away- the scourge of orange sodium vapour lighting.”

Music:

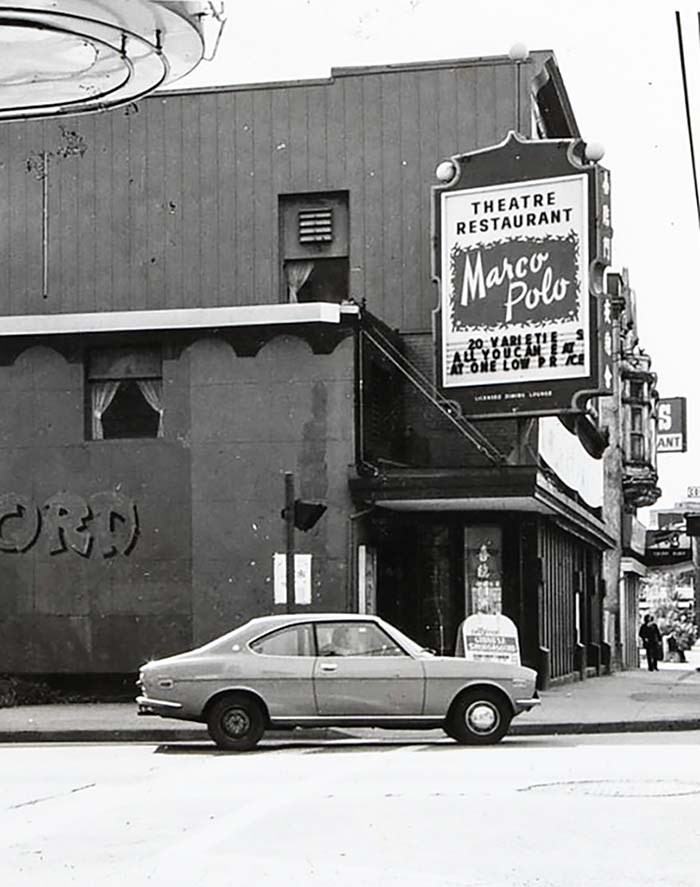

“I spent a lot of time in Kitsilano in the late 60s and through much of the 70s. I was there the July day when the Grateful Dead, who were in town for a three-day gig at Dante’s Inferno on Davie, were about to play a free concert near Engine 374 at Cornwall and Yew,” says Mark. “A couple of bands played first, then the neighbours complained about the noise, the cops showed up and the Dead, who’d been hanging around for an hour waiting to play (I stood next to Jerry Garcia, watching as, seated on a picnic table, he give guitar tips to a number of aspiring players), took off along with the rest of us, disappointed.”

“Mom and John lived on the top floor of 1872 W. 3rd. They had the Hippogryff Store beside the Stuart Building on W. Georgia & Stanley Park at the time. I moved down to live with Mom in 1967,” says William who was 10 at the time. “I had all the freedom I could wish for, it was a pretty magical time.”

The Beach:

“I used to live in Kits Point at 2080 Creelman Ave., a duplex with view of Kits Beach with all the beautiful people depicted in Bruce Stewart’s photographs,” says Thomas. “The bakery on Yew and Cornwall with all the wonderful breads and pastry and all the great restaurants along Yew and Cornwall. Lifestream was the melting point where you always met someone you knew. Saturdays we went to the only liquor store up on West Broadway to buy a gallon bottle of Calona wine (tasted horrible) and to find out where the parties were happening. Life was truly beautiful.”

Landlords:

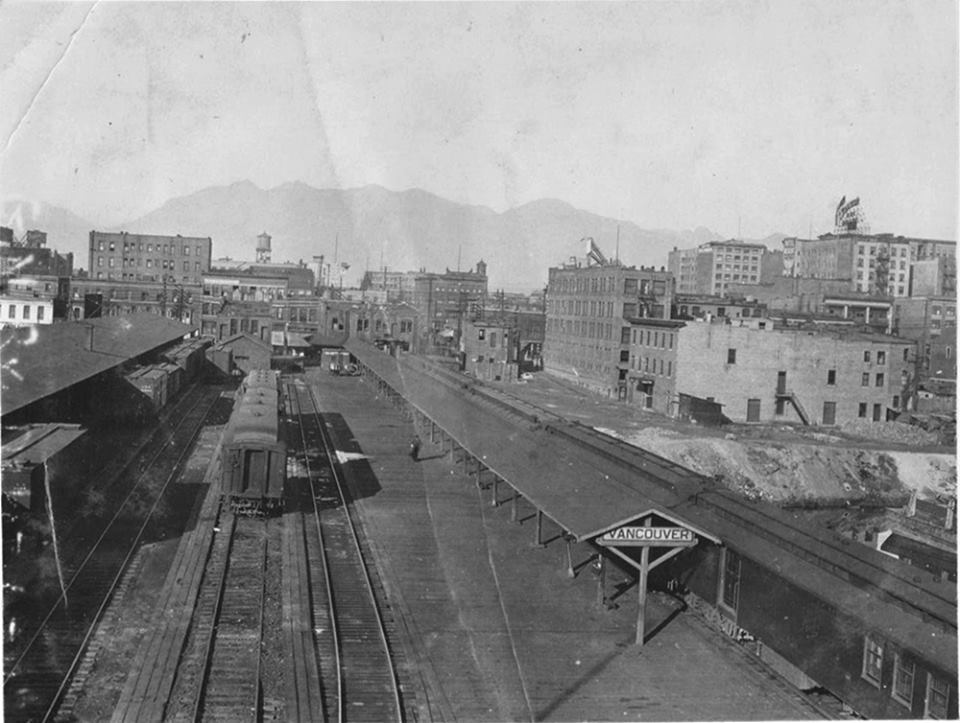

“In 1969-70, I lived at 2nd and Arbutus in an old wooden, three-storey house basement suite. I was 16 yrs old. The landlords were two ‘eccentric’ brothers Percy and Wes. They were retired, and Wes had worked for the CPR. They were hoarders, and there was canned food stacked everywhere,” says Nick. “The house was full of valuable antiques. Percy gave me a WW2 German Navy flag with the Swaztika on it. I gave it to a collector neighbour in East Van whose son was a friend of mine. Do you remember that HUGE rock that sat on the S.E. corner of 4th and Arbutus? The hippies used to sit on it.”

“I worked at the Lifestream warehouse. I used to pick up Peter in my VW van in White Rock and he would meditate on the floor during the commute to Richmond sometimes toppling over with sharp turns,” says Rob. “Lots of odd and funny hippy stories about the warehouse and the restaurant on 4th, my hangout. I’m still a health food freak!”

“I shot several photos of the Birkdale Apartments at 2235 West Broadway over a three year period,” says Gord McCaw. “There was an artists’ colony there and they decorated it in a few different incarnations.”

Bulletin Boards:

Says Bruce: “It appealed to me as it seemed like a one-stop ‘shopping’ setup: notices for everything from experimental theatre, cheap accommodation, yoga, clown workshops, spiritual healing, you name it! And, a place to rest one’s bones and pick over the free merchandise, on offer (the Fourth Avenue Free Box).”

“The Lifestream billboard. It was our internet,” says Will.

Says Jennifer: “It was like Tinder for hippies before social media.”

“I worked at CFUN in the early ’80s,” says Elizabeth. “A regular sight was the local guy with a big boat of a car, who had replaced front and back bumpers with flower boxes and always had his goat in the back seat.”

Related:

- Kitsilano in the ’70s: a photo essay

- The Nanaimo to Kitsilano Bathtub Race

- The Kitsilano Laneway House

- Kits Point and the Summer of 1923

- The Royal Hudson in Kitsilano

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.