BC Binning wasn’t just an important artist; as a teacher, he influenced architects such as Arthur Erickson, Ron Thom and Fred Hollingsworth. Where are his missing murals?

From Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

Artist and teacher:

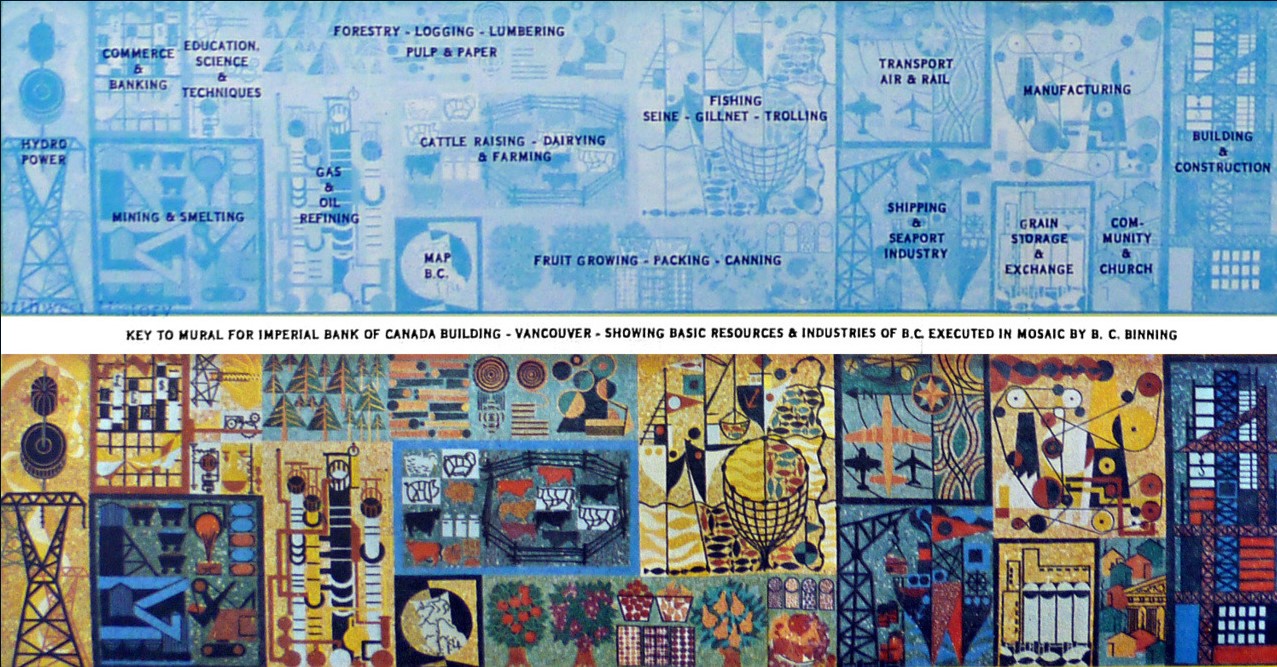

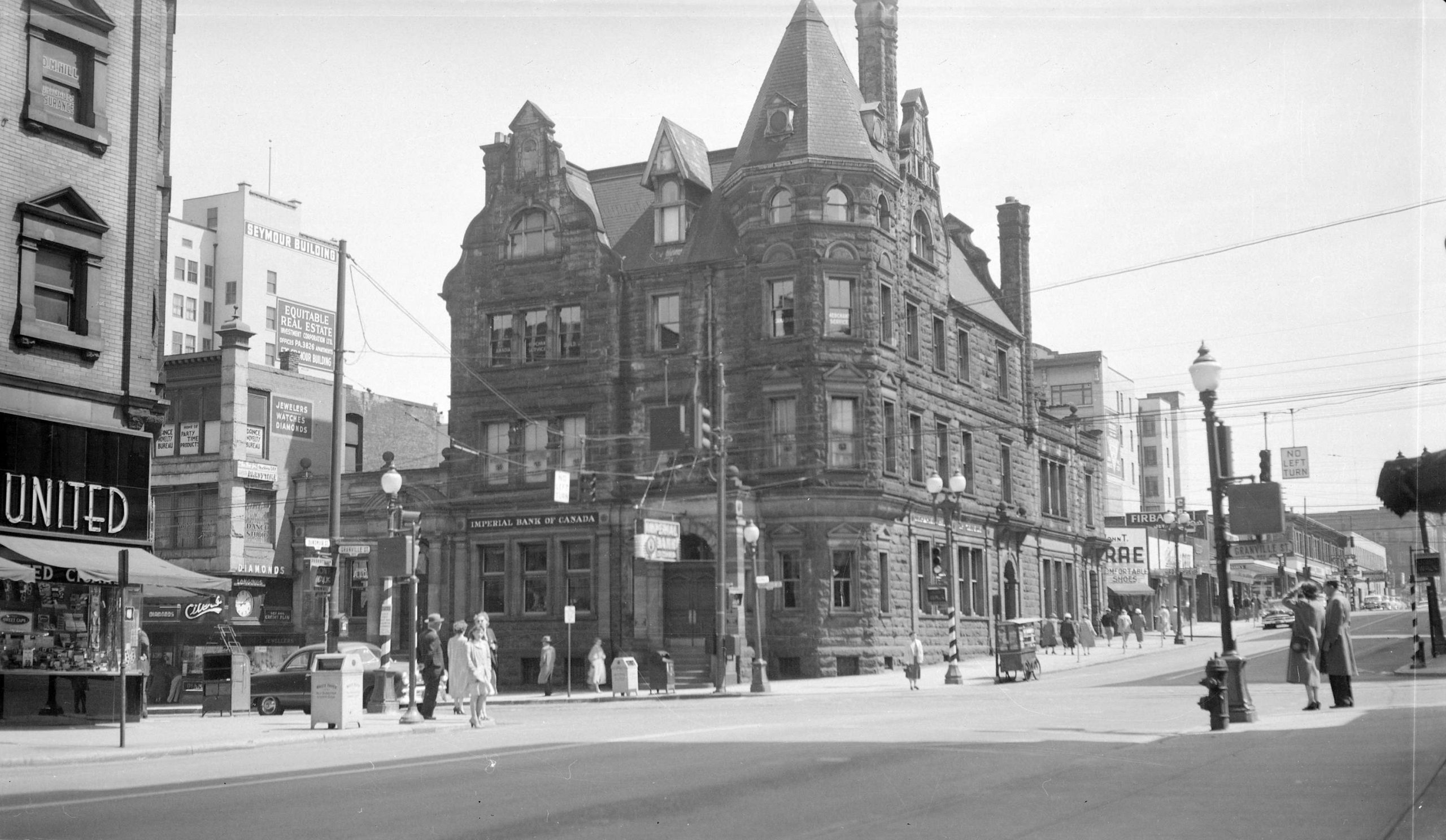

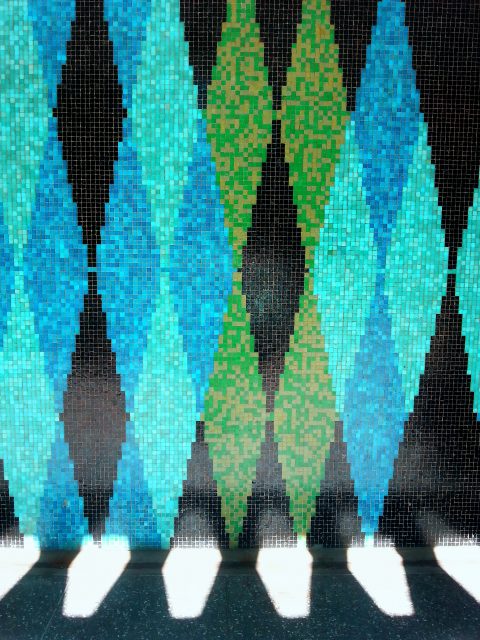

BC Binning wasn’t just an important artist; as a teacher, he influenced architects such as Arthur Erickson, Ron Thom and Fred Hollingsworth. His tiled murals are still outside the BC Hydro building (now the Electra Building) on Burrard Street, as well as in and outside his West Vancouver house which was designated a heritage building in 1999 and a National Historic Site in 2001.

Murals:

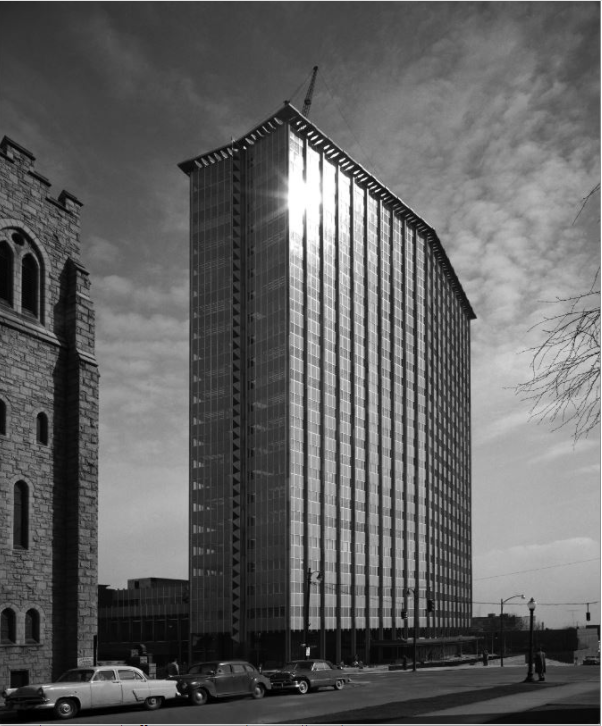

What you can’t see are the murals that he created for the old Vancouver Public Library on Robson Street, or the 76.2 metre-long mural he created in 1956 to wrap around the CKWX building on Burrard Street. That building was replaced by a 20-storey condo tower just 33 years later.

The University of British Columbia came up with most of the $8,000 needed to rescue a 7.3 metre section of the CKWX mural, while Andrew Todd, a Vancouver conservator was charged with prying Binning’s blue, green and yellow mosaic off the wall, tile by tile, and placing it on a rolled canvas for storage at UBC. “Oh my god it was tough to save,” Todd told me. “It was an abstract arrangement of one-inch glass tiles from Venice, much like his mural on the BC Hydro Building. And it was huge, maybe 20 feet by 10 feet (six by three metres) in sections.”

The saved section of the mural was to be installed on a proposed studio-resources building, which was to house the university’s fine arts program. The building was never built, and the mural has apparently disappeared.

© Eve Lazarus, 2022

Related: