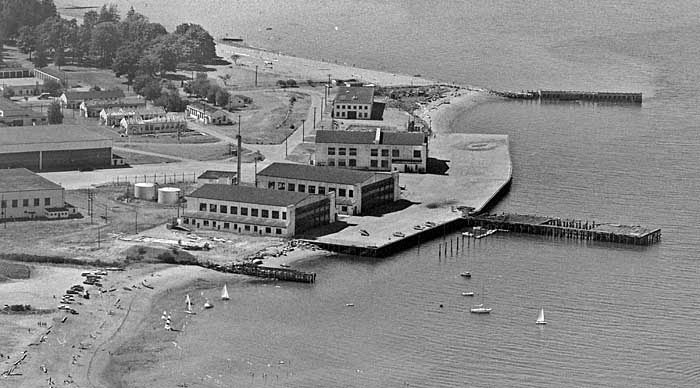

I’ve been to Jericho Beach dozens of times over the years and often bike along the path that snakes through Spanish Banks, Jericho and spits out onto Point Grey Road. It wasn’t until recently that I found out the area was once part of the largest military training base in Western Canada.

Flying Boats:

The base was built for flying boats and seaplanes in 1920 and included four large hangars and a military storage building.

Up until the outbreak of WW2, the flying boats were used mostly to head off rum runners, curtail illegal immigration and map the coastlines. From 1939 to 1947 the base functioned mostly as a training unit and repair depot. After the war, the land and base were used by the army for the next couple of decades until the City of Vancouver took it over in 1969 (and handed it over to the Parks Board).

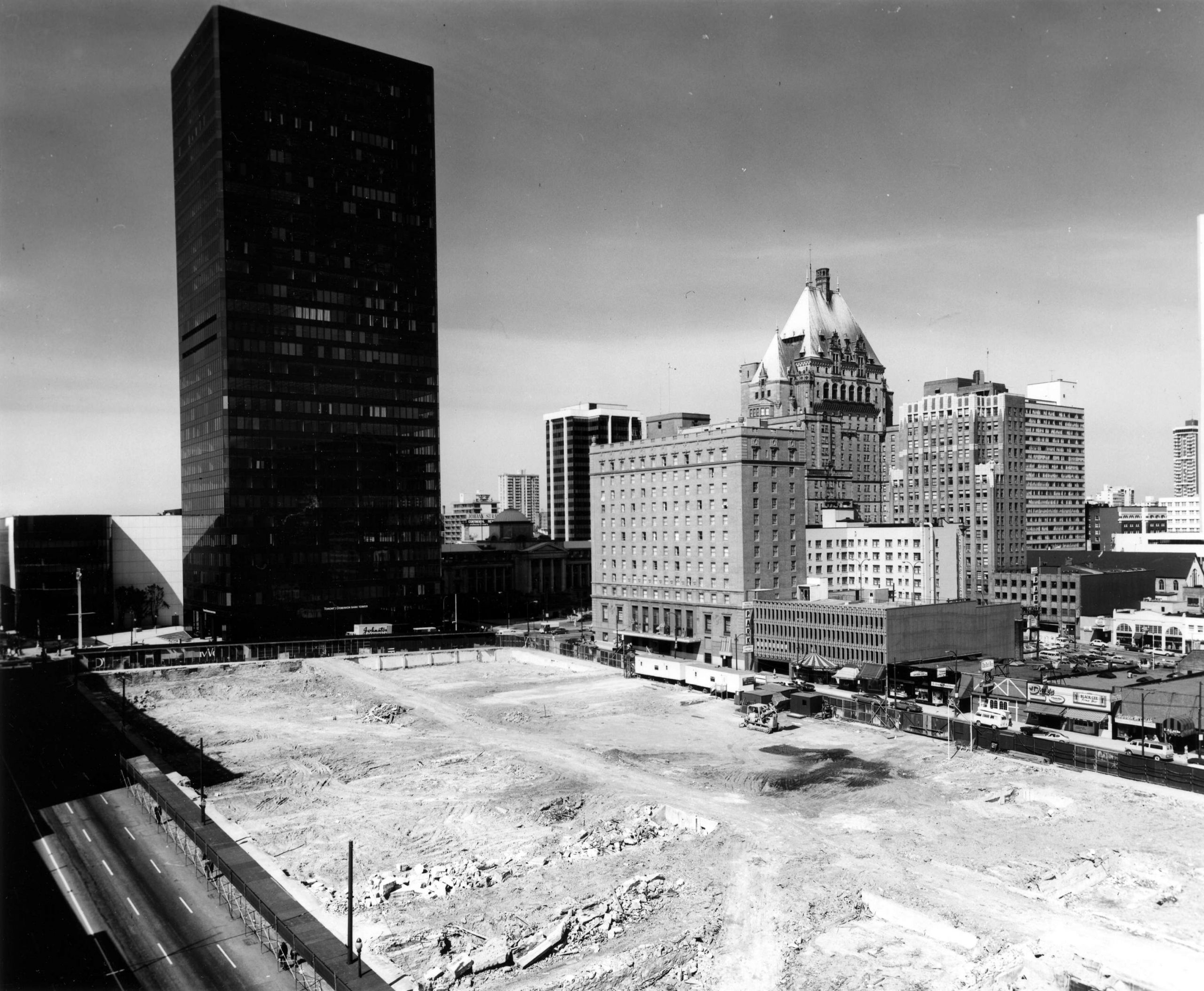

1969 was the start of a particularly egregious round of demolitions in Vancouver. In the downtown core which included heritage buildings such as the Vancouver Opera House, Granville Mansions, the York Hotel, the Colonial Theatre, the Strand, and five years later, the gorgeous Birks Building were all being cleared to make way for bland, boring high rises and underground shopping malls.

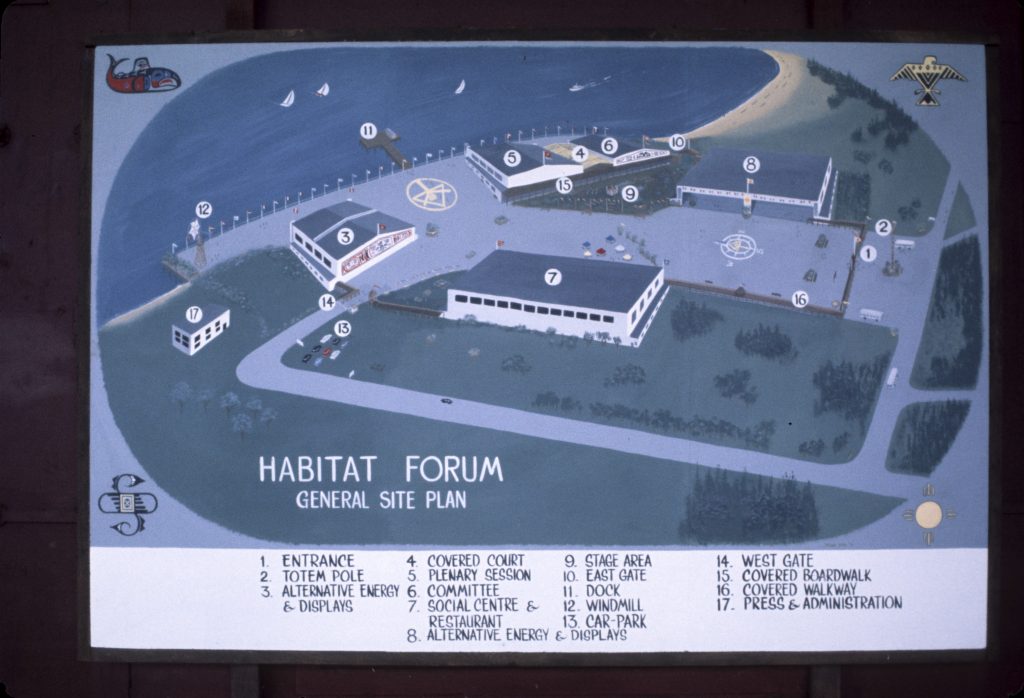

Habitat ’76:

Likely, the Jericho buildings would have met the same fate, but then along came the United Nations Conference on Human Settlement, Habitat ’76 and Alan Clapp. Clapp was the force behind Granville Island and the Dewdney Trunk Road Pleasure Faire in Mission, which was turned into a 60-acre village in September 1971 using deconstructed barns.

Clapp organized thousands of volunteers and transformed the Air Force hangars into two amphitheatres, a social centre, and a hall for exhibits primarily using driftwood from the beach and milled on site. Bill Reid created a huge mural on Hangar #3, which had been repurposed into a longhouse.

- Beneath Dark Waters: The Legacy of the Empress of Ireland Shipwreck by Eve Lazarus, coming April 2025. Preorder through Arsenal Pulp Press, online retailers or your your favourite indie bookstore

Habitat ’76 was a very big deal. It ran at Jericho Beach Park from May 27 to June 11, 1976. Pierre and Margaret Trudeau were there, and so were Mother Theresa, Margaret Mead and Buckminster Fuller.

For more posts like this one check out Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History.

Repurposing old buildings:

It demonstrated to the world how aging buildings and unused land could be saved and repurposed.

For over 6,800 digitized photos of Habitat 76 take a stroll through Vancouver Archives.

After it was finished there were various proposals on how to use the hangars and the land including an athletes training camp, an aviation museum, an arts centre and student housing.

And, then in the face of all this common sense and despite public outcry, the Parks Board tore it down. Two of the hangars were bulldozed in 1978 including the one with the gorgeous Bill Reid Mural.

In October 1979 hangar #7 burned to the ground. That was followed just over a month later by the destruction of hangar #5. Arson was suspected in both.

A few buildings have survived. The former Marine and Stores Building became the Jericho Sailing Centre. The recreation hall, and at one time a military gym, became the Jericho Arts Centre, and the former army barracks is the Jericho Beach Hostel.

Less than two years after suspected arson rid the Parks Board of some problem aircraft hangars, flames ripped through another Parks Board eyesore – the much loved Englesea Lodge at Stanley Park.

The Jericho Wharf built in the 1930s, came down in 2011.

With thanks to Carolyn Affleck who sent me her photo of the burning hangar from 1979 which inspired this post.

Related:

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

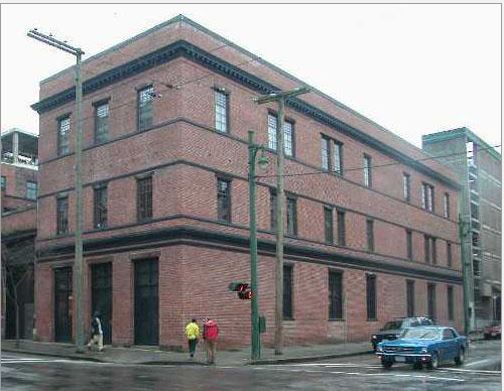

When Adams bought the brick building at the corner of Powell and Columbia Streets in 1991 it was abandoned and abused. Likely it would have gone the way of other historical Gastown buildings if he hadn’t seen its potential.

When Adams bought the brick building at the corner of Powell and Columbia Streets in 1991 it was abandoned and abused. Likely it would have gone the way of other historical Gastown buildings if he hadn’t seen its potential.