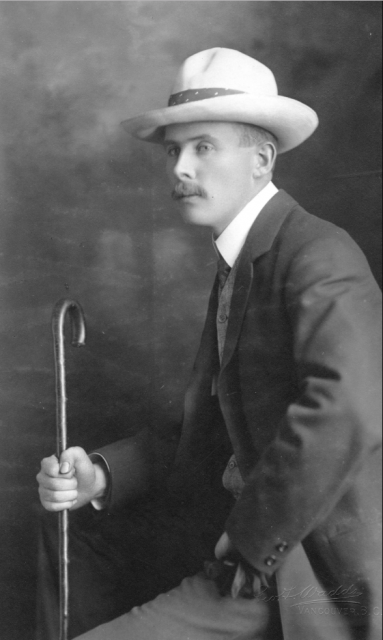

Charles Marega died on March 27, 1939.

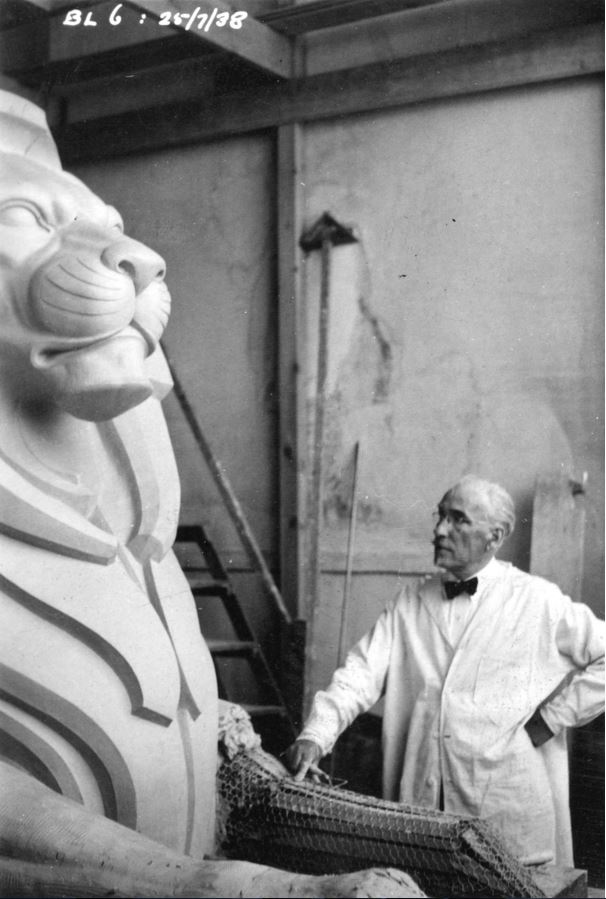

And, while you may not know his name you will know his work. Those are his two lion statues at the south end of the Lions Gate Bridge. And while the lions may be his most well known work, Charles (or Carlos as he was christened) was a prolific sculptor in Vancouver.

I first heard of him when I was writing about Alvo von Alvensleben for At Home with History. Alvensleben owned what’s now part of Crofton Girl’s School and the 20 acres it sat on at West 41st Avenue and Blenheim in Kerrisdale. He hired Marega to carve a magnificent riot of gargoyles, bats, rabbits and assorted weird faces in the white plaster of his dining room ceiling.

At that point Marega wasn’t very well known, but he had just shocked Vancouver’s sensibilities by carving nine topless terra cotta maidens on L.D. Taylor’s building (now the Sun Tower), which likely appealed to the flamboyant Alvensleben.

At that point Marega wasn’t very well known, but he had just shocked Vancouver’s sensibilities by carving nine topless terra cotta maidens on L.D. Taylor’s building (now the Sun Tower), which likely appealed to the flamboyant Alvensleben.

Other commissions include the bronze bust of David Oppenheimer, Vancouver’s second mayor at the entrance to Stanley Park; the statue of Captain Vancouver in front of Vancouver City Hall; the 14 famous people on the Parliament Buildings in Victoria; and the drinking fountain that sits in Alexandra Park to honour Joe Fortes.

As Marega was creating sculptures for public places, his plaster work was also in demand for private mansions. His work can be found at Rio Vista on South West Marine Drive, Hycroft in Shaughnessy Heights, and Shannon at 57th and Granville.

While Marega worked for the wealthy, in the 1930s he and his wife Bertha lived a humble existence at 1170 Barclay Street–a simple two-storey grey stucco apartment building in the West End with the improbable name of “The Florida.”

To make ends meet, Marega taught at the Vancouver School of Decorative and Applied Arts (the forerunner to Emily Carr Institute of Art and Design). In fact, he had just finished teaching a class in 1939 when he had a heart attack and died. He was 68.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.