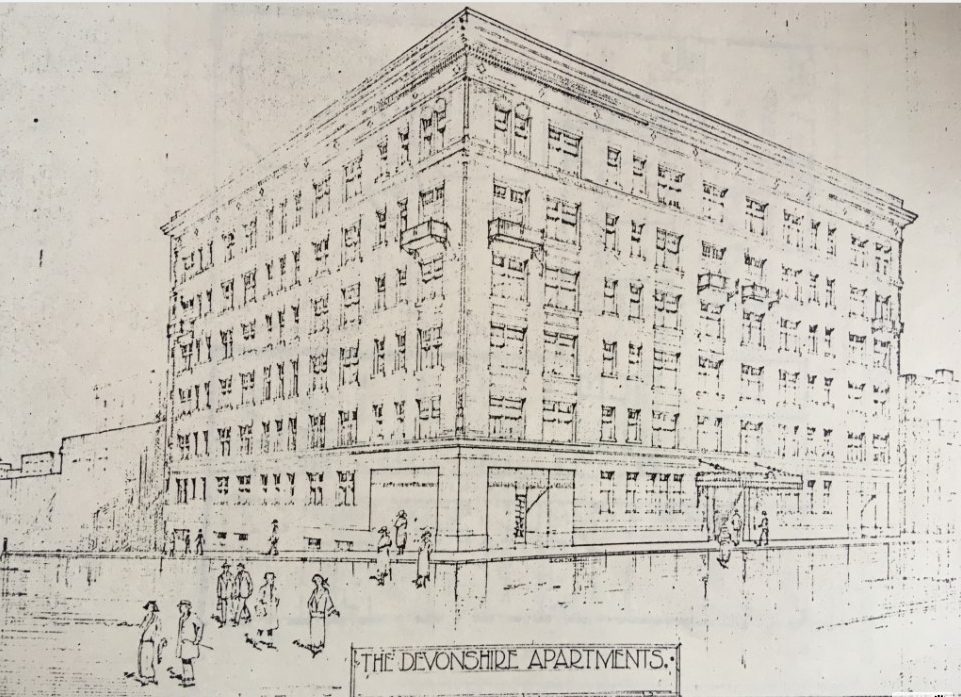

The Devonshire Hotel on West Georgia was demolished July 5, 1981 to make way for the head office tower of the Bank of BC.

Story from Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

Devonshire Apartment Hotel:

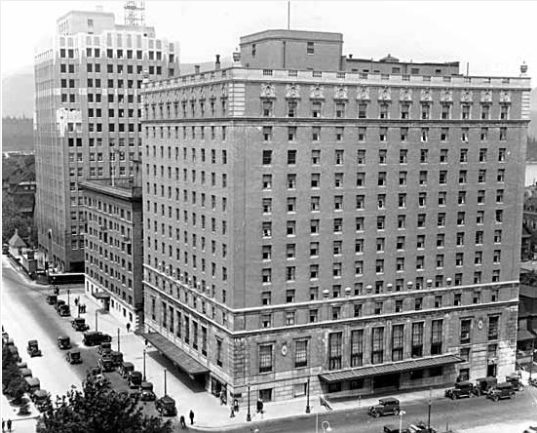

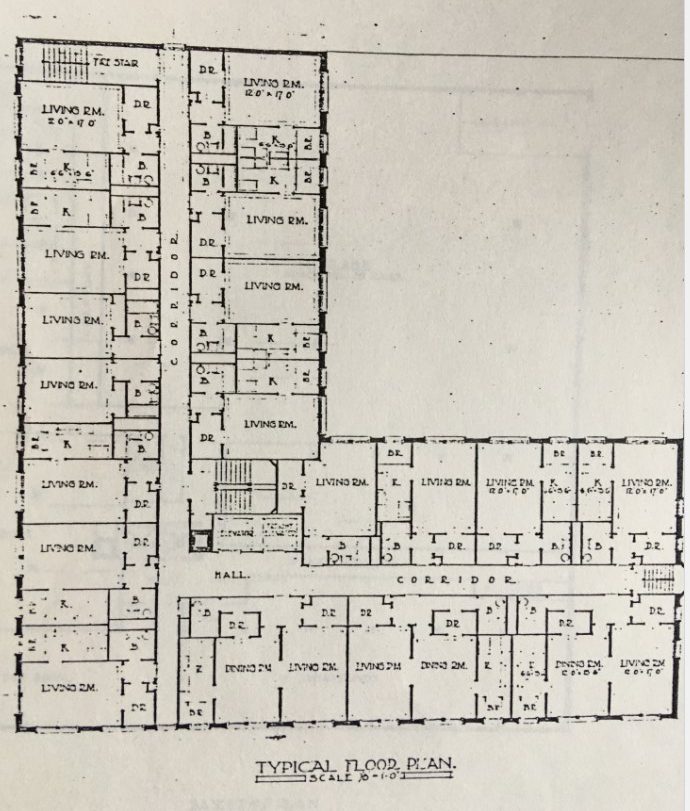

The Devonshire originally opened as an apartment building, but within a few years was operating as the Devonshire Hotel. The building sat between the Georgia Hotel and the Georgia Medical-Dental Building and closed 40 years ago this month to make way for the head office tower of the Bank of BC.

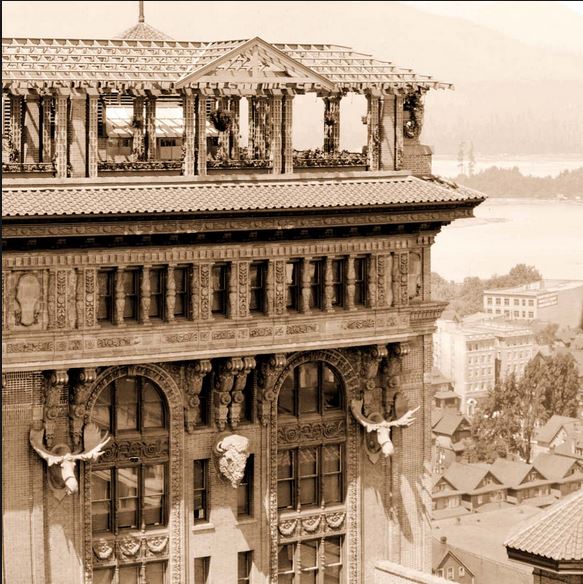

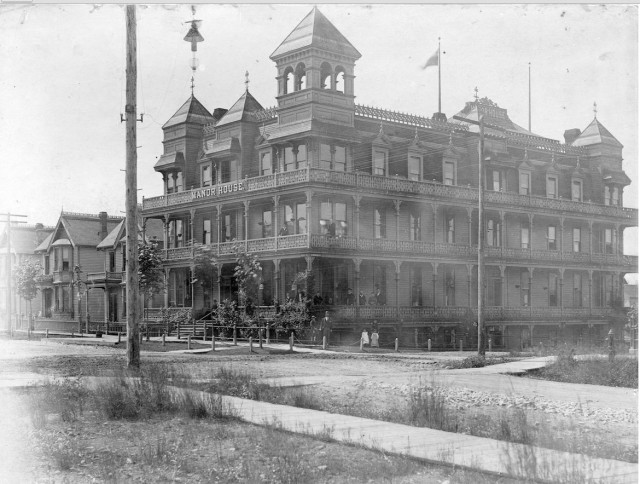

The Devonshire, which was designed by McCarter Nairne (the architects later designed the GM-DB next door and the Marine building) replaced Georgia House, which was actually two houses joined together by a long pergola-like verandah and known for its dances and parties. According to one newspaper story, some of the Devonshire suites had grand pianos, likely because Walter Fred Evans, the owner was a piano distributor and involved with the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra.

Louis Armstrong:

I never saw the Devonshire, but I love one of its stories.

According to newspaper reports, after being kicked out of the racist Hotel Vancouver in 1951, Louis Armstrong and his All Stars walked across the street and were immediately given rooms in the Devonshire.

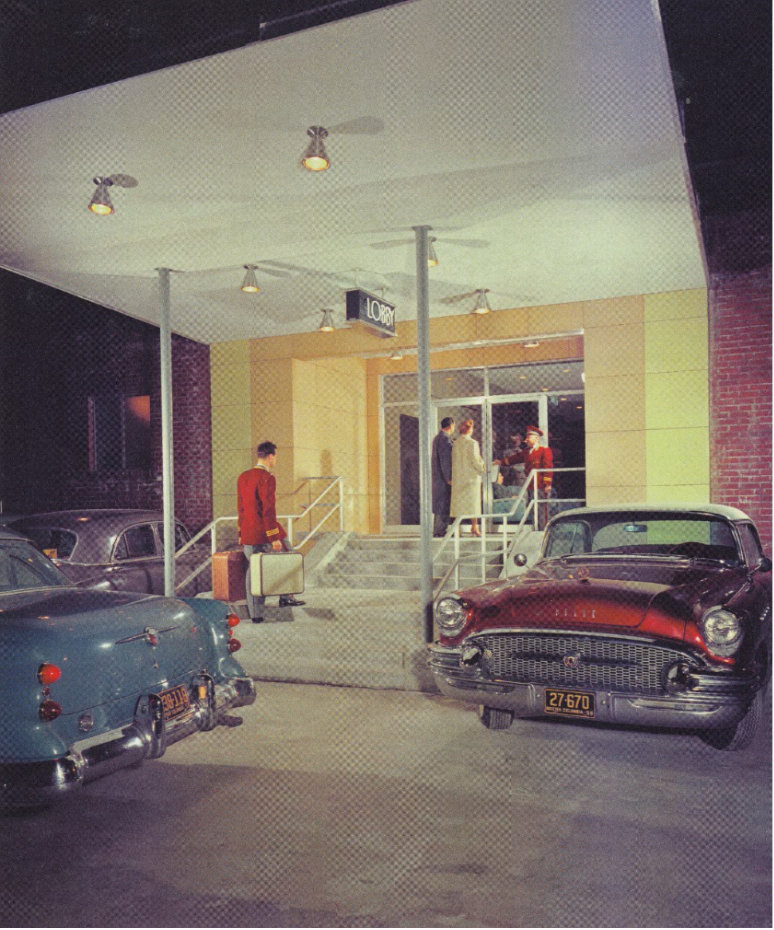

A photo of a travel-weary Armstrong sitting on his suitcase in the Devonshire’s lobby appears on the cover of his album in 1951.

Supposedly, Duke Ellington, Lena Horne and the Mills Brothers wouldn’t stay anywhere else.

Red Jackets and Corned Beef Sandwiches:

Former Globe and Mail reporter and author Rod Mickleburgh was there when the Devonshire was demolished. “I thought the loss of the Dev was awful. The Dev was the poor cousin of the Hotel Georgia, an old-fashioned pile-of-bricks hotel in a great location right downtown,” he told me. “I loved the corned beef sandwiches and glass of beer I’d get in their beer parlour, served, of course, by waiters in red jackets on small, round, terry cloth—covered tables. A glass of beer was twenty cents—you gave the unionized waiter a quarter.”

I forgot to ask Rod if he remembered seeing William “Fats” Robertson there having a beer. Fats, along with a bevy of judges, lawyers, doctors and stockbrokers was a regular until 1978 when he was caught heading up a major drug smuggling ring and sentenced to 20 years.

Dal Richards, Manager:

Local celebrity Dal Richards was the resident manager from 1979 to its closure two years later. Eleni Skalbania was an investor in the late 1970s. She followed that with a partnership in the Hotel Georgia, and in 1984, opened her own boutique hotel, The Wedgewood on Hornby Street.

Related:

Sources:

- Province, November 13, 1932, April 30, 1981

- Vancouver Sun, April 29, 1981, January 14, 2017

- Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus