Before we had the Vancouver Aquatic Centre, there was the Crystal Pool.

The story is from Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History.

Crystal Pool:

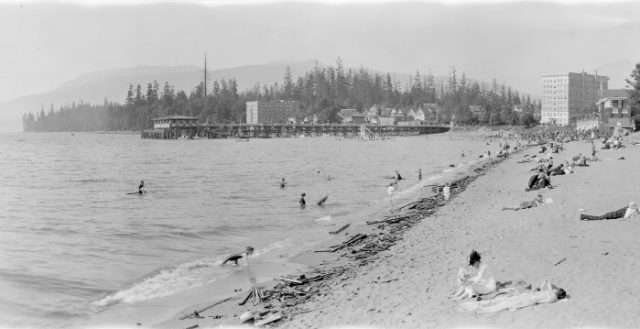

Joe Fortes taught hundreds of children how to swim in English Bay, If the much-loved life guard were still alive when Crystal Pool opened in July 1929, it’s hard to imagine that the parks board would have got away with separate swim days—six days for whites, one day for “coloureds and Orientals”*—segregating their mostly young customers for the next 17 years.

Sunset Beach:

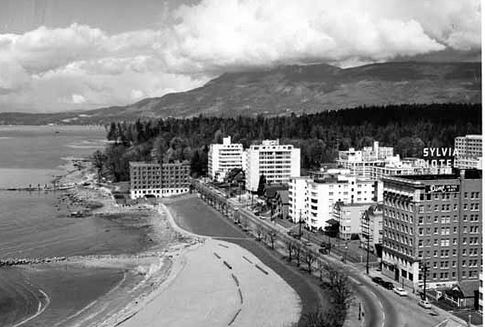

The salt-water pool at Sunset Beach was built as part of a swanky private club called the Connaught Beach Club. As well as a pool, there were plans to include tennis, badminton and squash courts, Turkish baths for men and women, a beauty parlour, barber shop, roof garden and a ballroom. But the operators went broke, and the contractors finished only the pool for shares in lieu of cash.

The city bought the land in 1939 and the parks board held the lease. The pool had bled money during the Depression and some of the stunts to bring in customers included watching George Burrows, superintendent of beaches and parks leap off the three-metre board, tied in a gunny sack for his underwater escape act. Gordon Ross, manager was talked into diving through the air to hit a ring of flame on the water, while Percy Norman, swim coach would wrestle contenders on a platform until one fell into the water. Another draw was throwing 1,000 pennies into the pool and having the kids dive for them. The kids would later return them to the pool by buying sweets at the concession stand. On Saturdays, a 15-cent admission got kids a hot dog, Coke and bus fare home.

Vivian Jung:

In 1945, 21-year-old Vivian Jung was stopped from getting the life-saving certificate she needed to join the Vancouver School Board as a full-time teacher because she wasn’t allowed to swim in Crystal Pool with the white folk. Her students and colleagues refused to go to the pool without her, and the segregation rule was finally abolished. Vivian became the first Chinese Canadian teacher hired by the Vancouver School Board and taught at Vancouver’s Tecumseh Elementary School for 35 years. In 2014, the year that she died, Jung Lane was named for her. Fittingly, the lane runs right by Sunset Beach.

In 1966, Harry McPhee head of the Seahorse Swim Club went to war with the parks board in an effort to save the pool from demolition for competitive swimmers, even though the facility was aging and losing money. “Perhaps it was a fluke by the builders in the first place, but it’s the right width, the right length, the right everything,” he told a reporter. “It may not look all that glamorous, but it’s got something of the Stradivarius about it.”[2] McPhee lost. Crystal Pool was demolished, though Vancouver gained the Aquatic Centre, which opened in 1974.

[1] “Colour Bar Removed from Crystal Pool.” Province, November 6, 1945

[2] Chester Grant. “Harry’s Campaigning to Save Crystal Pool.” Vancouver Sun, December 3, 1966

Related stories:

© Eve Lazarus, 2022