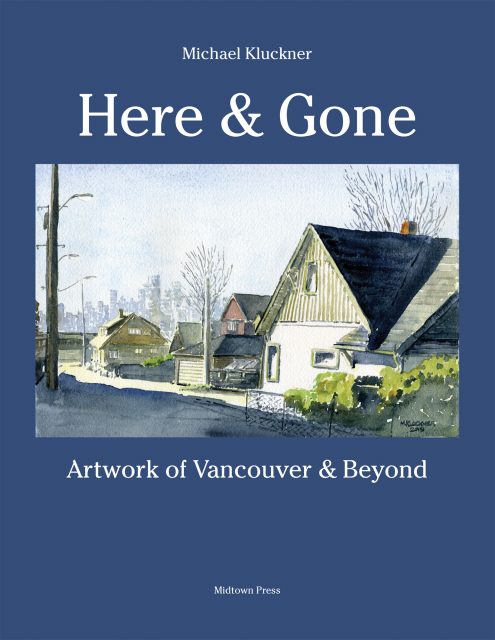

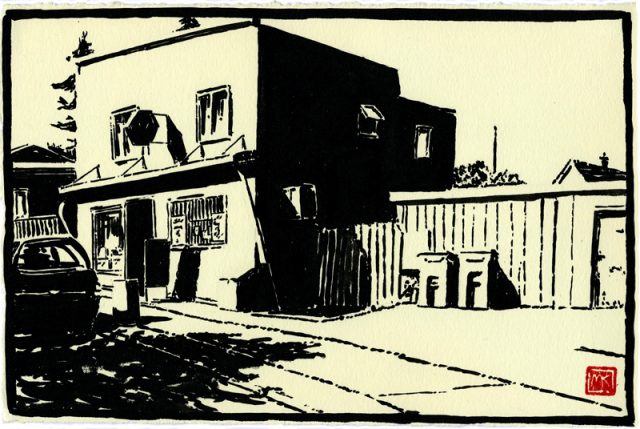

I was riding my bike along Point Grey Road this week and snapped a few photos of the Peace House. It’s an interesting looking place, and as it turns out, has quite the past.

3148 Point Grey Road:

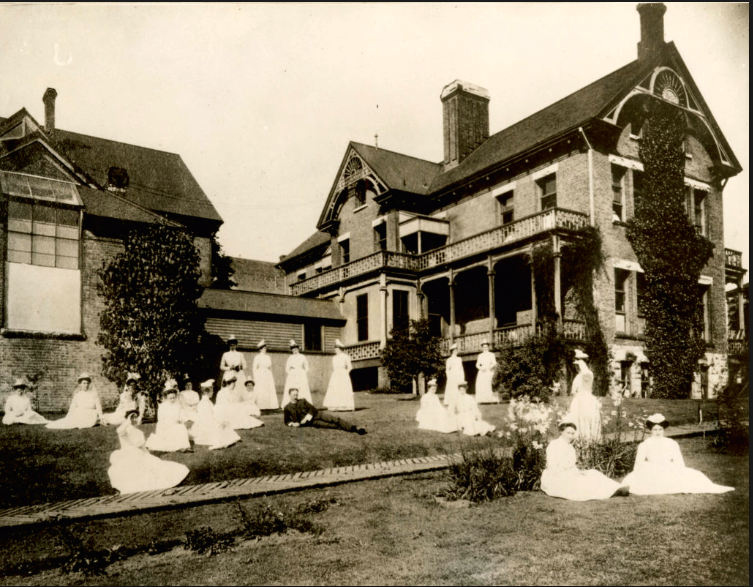

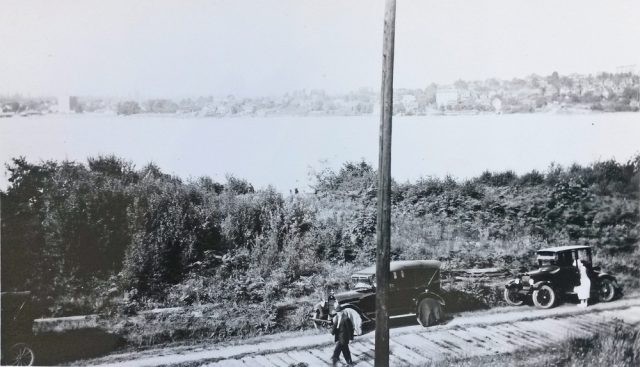

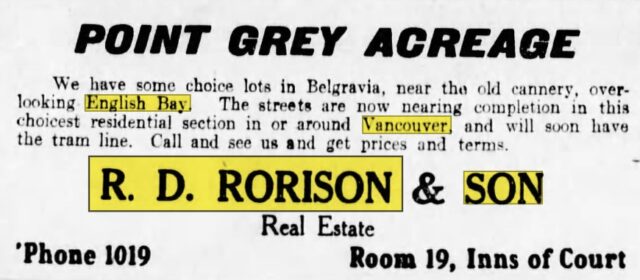

It was built in 1908 by R.D. Rorison who was an early real estate agent and developer. His company bought the English Bay Cannery in 1905, tore it down and used the wood to build part of the house.

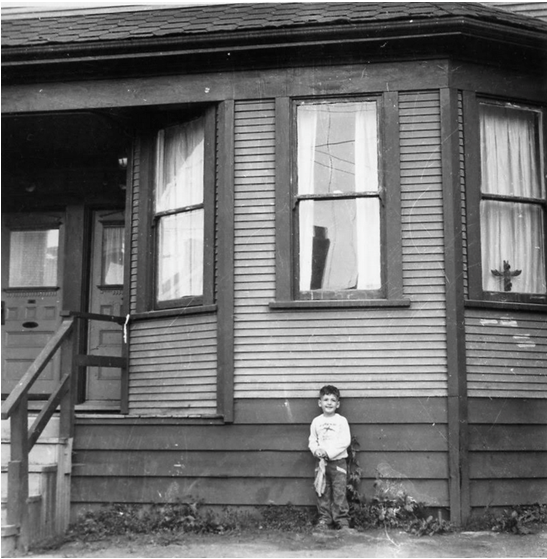

In 1965, the house attracted an anti-nuclear group who were protesting the storage of nuclear weapons at the Comox RCAF Base. The leader was a 22-year-old UBC student named Peter Light, who spent most of his time organizing a protest march from Victoria to Comox. The house became widely known as the Peace House and freaked out its more conservative neighbours.

From a May 21, 1965 Province article: “The city has lost patience with the Peace House. The zoning appeal board has rejected a presentation that a group of bearded, sandal-wearing peace demonstrators who occupy the house at 3148 Point Grey Road should be classed as a philanthrophic organization.”

And on that same day in the Vancouver Sun: “The house is run down, dirty shirts hang in the window, fires have been started in the middle of the front room floor using chairs for fuel, and that newspaper reports of free love in upstairs rooms are true because they could look in and watch. They are degenerating the outlook and spirit of young Canadians.”

The Afterthought:

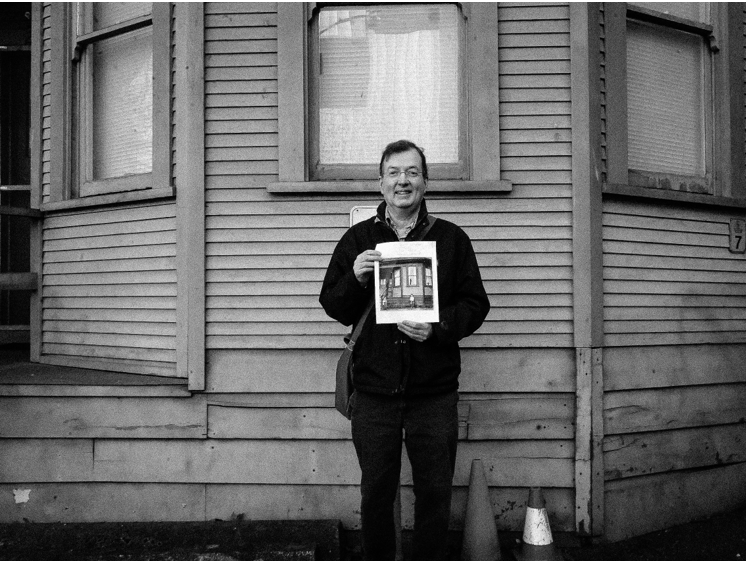

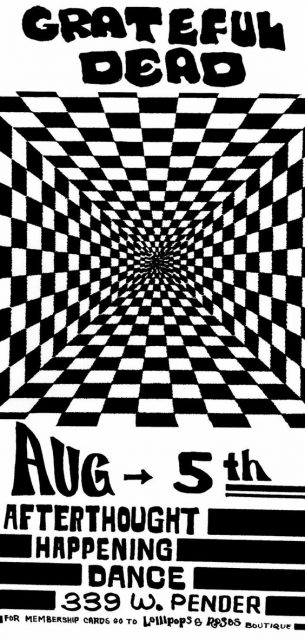

A couple of years back when I was chatting to Jerry Kruz about his exploits as a 17-year-old promoter, he told me he lived in a room at the Peace House while he was bringing acts to the Afterthought. He brought in Country Joe and the Fish, the Steve Miller Band, and in 1966, paid the Grateful Dead $500 to play there. The band also crashed at the Peace House. According to Heritage Vancouver Society, so did other cultural icons of the day such as Timothy Leary, Baba Ram Dass and Allen Ginsberg.

In 1968, the house played a role in Robert Altman’s thriller That Cold Day in the Park. Grant Lawrence has a great story about Ginger Baker, the legendary drummer from Cream staying there. “It was essentially a crash pad for local and wandering hippies and touring bands,” writes Grant.

Michael Kluckner tells me that Jeannette and her husband, renowned artist Jeff Wall, lived at the Peace House around 1970. “The house came up for sale then for $17,000, but had no takers partly because it had a huge sawdust-burning furnace that needed replacing,” says Michael. A woman from Toronto bought it, and according to rumour, hired architect Arthur Erickson to do some remodelling.”

The six-bedroom house is currently assessed at $4.4 million.

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.

Further Reading:

- Michael Kluckner’s Vancouver Remembered

- Grant Lawrence: The Rise and Fall of Canada’s Hippie Mecca

- A Short History of the 2400 Motel