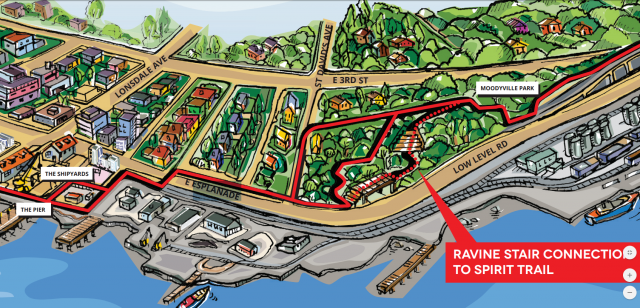

At the end of last week’s blog, I left you at Moodyville Park, the only thing left of a once thriving town. Now hop back on your bike and follow the signs west along First Street East—and be careful of those construction trucks! I imagine in another year or so this area will be unrecognizable, but occasionally you’ll see a bungalow–the lone standout in a sea of rubble.

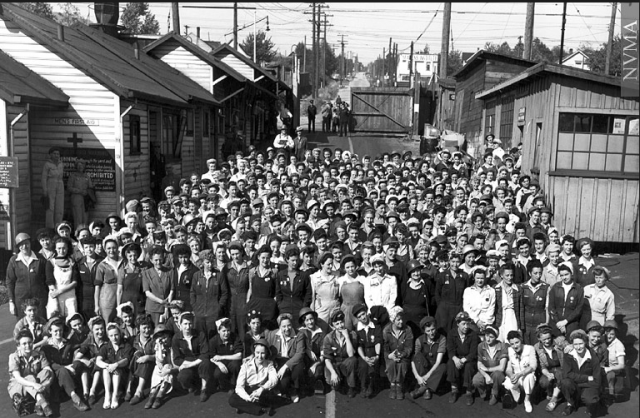

Some of those holdouts were built during WW2 when Wartime Housing, a crown corporation, built tracts of neat cottages for shipyard workers. According to North Vancouver Museum and Archives, rents averaged $20 per month plus $1.35 for water services. The website says about 100 wartime houses still survive, but I’m not confident how current that is.

You’ll see signs taking you down the squiggly path and onto Alder Street and along the working waterfront.

The old Pacific Great Eastern (PGE) Railway-North Van’s first train station—is boarded up and stuck behind a chain link fence until a new home is found for it (I hope).

On January 1, 1914, the PGE began service from this station at the foot of Lonsdale Avenue to Dundarave. At the time the plan was to extend the tracks to Squamish, but that didn’t eventuate and the railway only went as far as Horseshoe Bay. The railway service ended in 1928, and the station became a bus depot, and then was used as offices until it was moved to Mahon Park in 1971. It was spiffied up and returned to its home at the foot of Lonsdale in 1971, and moved to its current location in 2014.

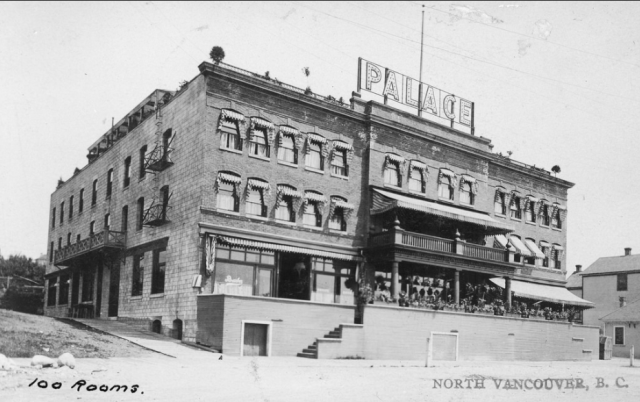

The Spirit Trail takes you along Esplanade and down St. George’s to Victory Ship Way. If you look up the street you’ll see a 15-storey condo tower at East 2nd called the Olympic. In 1906 Lorenzo Reda built a brick hotel in that spot. Within two years, he added more rooms and a dance hall, and in 1908 the Palace Hotel boasted that it was “the only hotel in British Columbia with a roof garden.” Reda died in 1928. The hotel became the Olympic, and by the ‘70s (when it was known locally as the “Big O”), it was hosting rock bands and strippers. It was demolished in 1989.

.Aside from a couple of the old shipyard buildings and artifacts, most of the buildings have been torn down and replaced with condos. This was a hopping place during WWII, and Burrard Dry Docks was the first to hire women in significant numbers and pay them decent wages.

And some of you may remember the Erection Shop that sat at the bottom of St. Georges until political correctness made the shipyards take the sign down for Expo 86.

We’ll start at Shipyards Coffee at Lonsdale Quay next week for a chat about the history of the area.

The North Shore’s Spirit Trail – Moodyville (part 1)

Pemberton to Capilano River (part 6)

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.