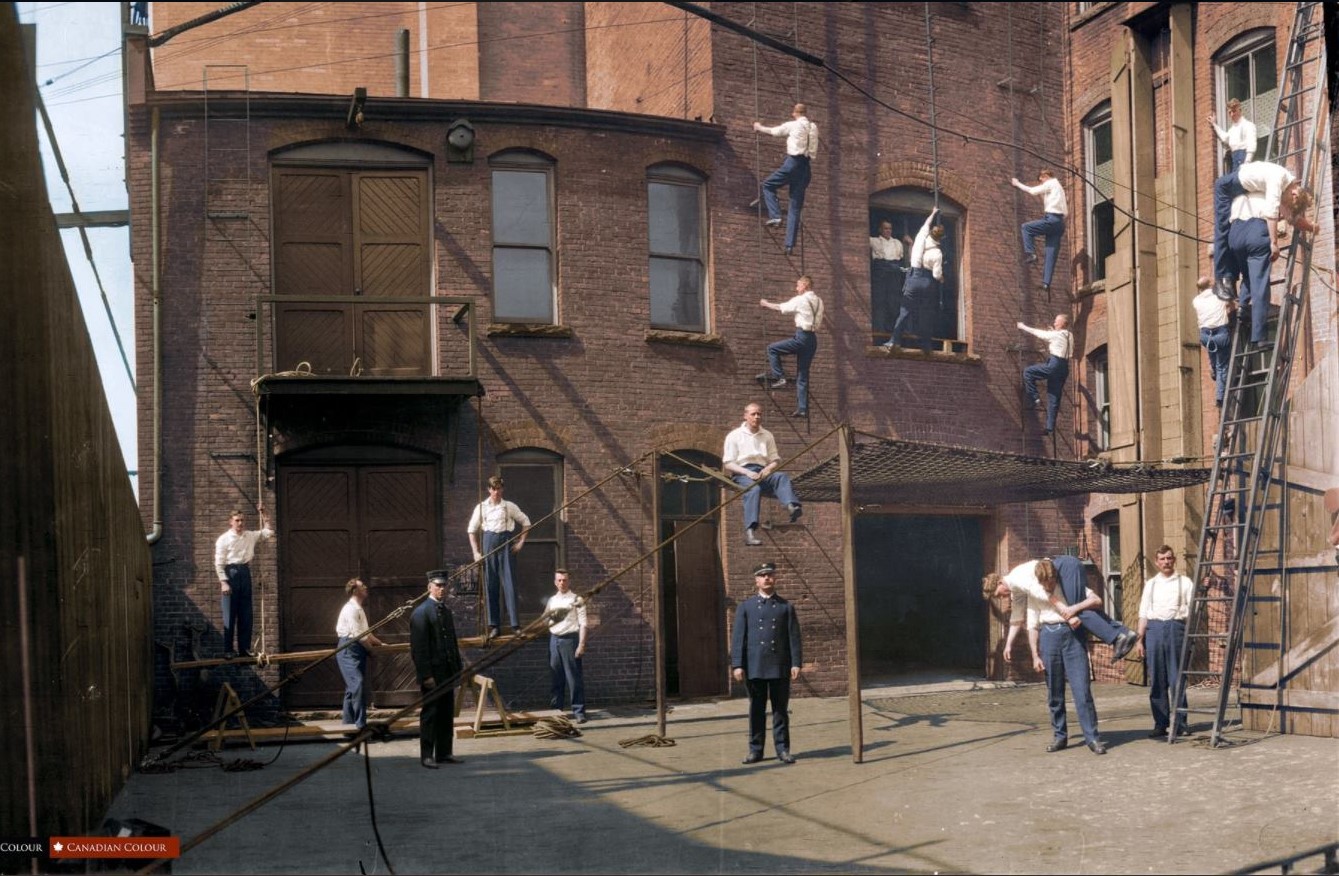

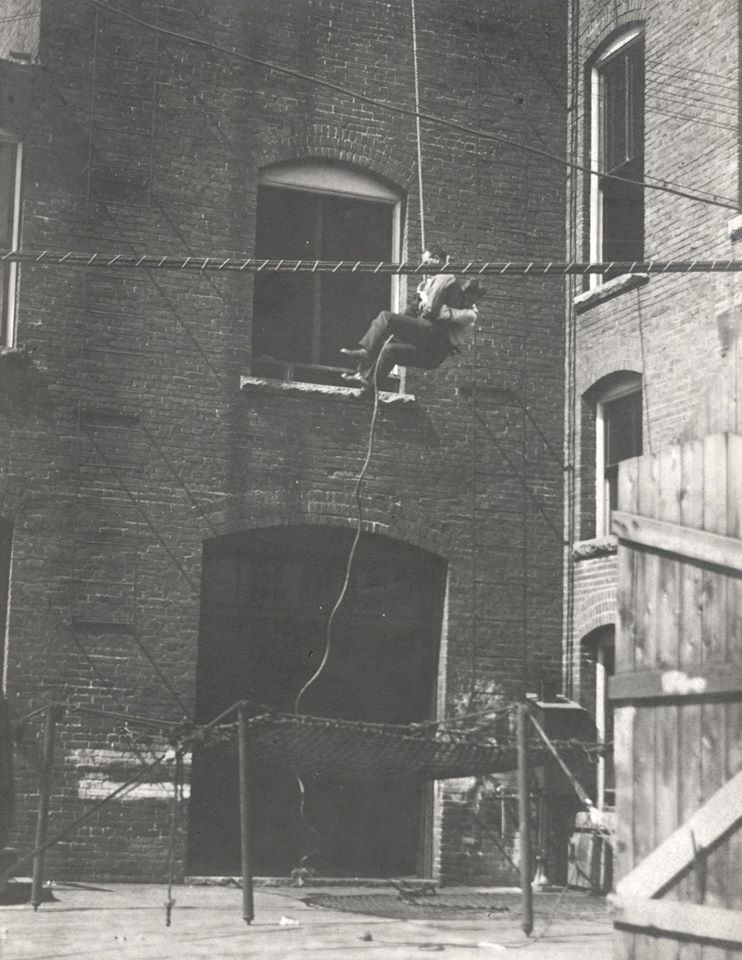

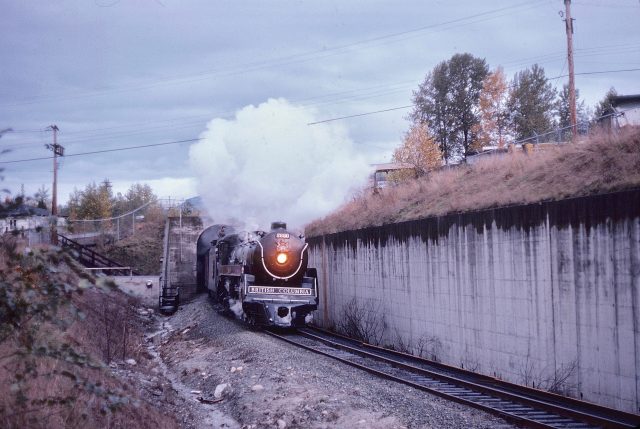

Angus McIntyre took this photo of the Royal Hudson at Arbutus and Broadway in 1977 travelling to the US on a three-week promotional tour

Going South:

This photo of the Royal Hudson travelling along the Arbutus corridor at Broadway on March 20, 1977 is one of my favourite Angus McIntyre photos. If you’re a regular follower of my blog, you’ve already seen some of his wonderful early street photography. But it wasn’t until I was writing Vancouver Exposed: Searching for the City’s Hidden History that I did some digging to find out why locomotive 2860 was chugging its way from the old BC Hydro yards in Kitsilano across the border into Blaine.

Turns out that it was part of a three-week promotional tour spearheaded by Grace McCarthy, travel minister and Vancouver Mayor Jack Volrich. The steam engine hauled seven cars filled with BC artifacts. Because it was Queen Elizabeth’s silver jubilee, one of the cars had been turned into a Royal suite complete with life-sized waxworks of Her Majesty, Prince Philip and Prince Charles. Three other cars carried a variety of models, maps and posters of BC’s resource-based industries.

The Photo:

“I heard a steam whistle and I knew that something was going along the Kitsilano trestle. I could see smoke coming up from that area, so I got into my car and drove recklessly across Broadway, parked near Arbutus, got out of my car and took a grab shot. There was no time to set up,” says Angus

When Angus had a show of his photographs at the Baron Gallery in 2012, legendary photographer Fred Herzog attended. He bought a copy of Angus’s photo and told him that some of his best photos were grab shots.

History:

For 25 years, the Royal Hudson steam locomotive 2860 had a regular run from North Vancouver to Squamish.

That ended in 1999 when the engine’s boiler gave out. Aside from a couple of “appearances,” the engine is on display at the West Coast Railway Heritage Park in Squamish. The Arbutus corridor is now a fancy bike and pedestrian trail. Abe Van Oeveren tells me that the last train to run on the line was on May 31, 2001. “CPR 1237, affectionately known as ‘Queenie” lifted the last two empty malt hoppers from the Molson’s brewery by the Burrard Bridge.”

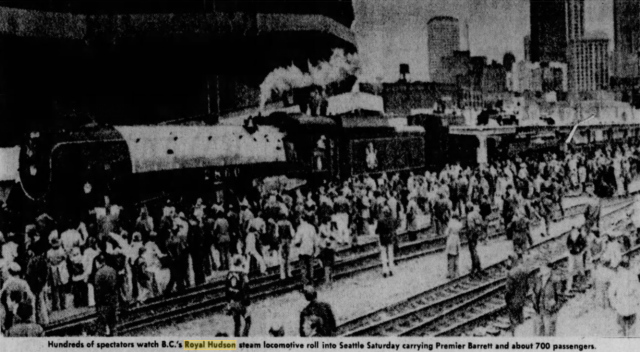

On November 1, 1975 the Royal Hudson took 800 passengers on a trip from North Vancouver to Seattle for a meet-up with the stream-powered American Freedom Train, which was on a 21-month tour through 48 states. It was the first time a passenger train had crossed the new Second Narrows railroad bridge and travelled through the Thornton Tunnel.

Related Stories:

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.