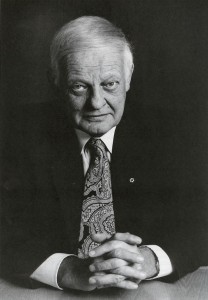

Barry Downs architect designed his gorgeous West Coast Modern house in West Vancouver in 1979. He lived there until his death in July 2022 at 92.

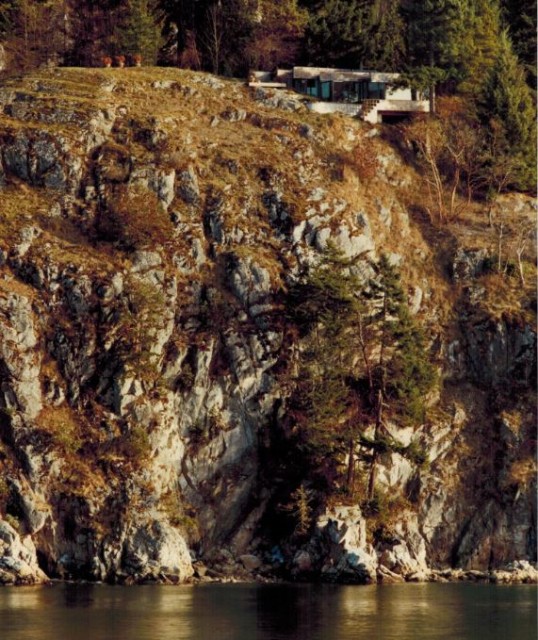

Barry Downs house sits on top of a cliff 120 feet above West Vancouver’s Garrow Bay. The house is almost invisible from the busy street and built on multiple levels, with lots of glass that connects the indoors with the out.

Rapidly disappearing:

Rapidly disappearing:

Most people don’t think of these gorgeous mid-century homes as “heritage,” but many are listed on the Heritage Register. Because they are typically small houses on large view lots, they are rapidly disappearing.

Barry figures we’ve lost about 50 percent of our mid-century housing stock.

Each step through the Downs’ house is like a journey of discovery. A window in the bathroom looks out onto the forest. Another window gives a view of Bowen Island, and another a glimpse of the rocky exterior. But it’s not until you step into the dining room that you can truly understand the brilliance of Barry’s design. The Strait of Georgia, Vancouver Island and the B.C. Coast line leaps out through floor to ceiling glass windows, and just for a moment it’s disorienting, like being suspended in space.

Focus on the landscape:

“To me, it’s all to do with emotion, and you derive that from the building and its setting,” says Barry. “The focus for me has always been the landscape, the garden, the seasonal world.”

Barry trained at Thompson, Berwick and Pratt and worked with some of the city’s most exciting and imaginative architects. Arthur Erickson, Ron Thom, Fred Hollingsworth, Paul Merrick and B.C. Binning, at one time all worked under the guidance of Ned Pratt. Barry left to form a partnership with Fred Hollingsworth in 1963, and six years later he and Richard Archambault launched their own company with residential houses as their mainstay.

“We built on narrow lots with simple and affordable post and beam houses. We designed houses that pushed up through the trees, that revolved around the idea of the big room, surrounded by the garden, and the view of the changing seasons,” he says.

Barry, a softly spoken man now in his 80s, is as low key as the houses that he designs. He’d just like to see more of them remain.

Related:

- Our Missing West Coast Modern: What were we thinking?

- West Coast Modern on Display

- Ned Pratt’s West Coast Modern Home

- West Coast Modern: Selling Architecture as Art

- West Coast Modern Architecture

- Selwyn Pullan Photography: what’s lost?

© All rights reserved. Unless otherwise indicated, all blog content copyright Eve Lazarus.